City council members on Wednesday grilled education department officials on school segregation at a joint hearing of the Education Committee and Civil and Human Rights Committee.

The sharp questions and answer session took place just weeks before the 65th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision.

The atmosphere was a stark departure from just five years ago, when council members questioned education department officials about diversity issues in a school system that remains among the most segregated in the country. Back then, Mayor Bill de Blasio and his previous schools chancellor, Carmen Fariña, steadfastly refused to even mention the words “integration” or “segregation.”

But Farina’s successor, Richard Carranza, has bluntly questioned the ways in which schools sort students and fiercely defended the need for and benefits of integration. But he has also faced criticism for overseeing only narrow steps to address segregation, focusing mostly on a city plan to change admissions at just eight elite specialized high schools.

Speaker Corey Johnson blasted the city for delaying specific reforms while waiting for an appointed advisory board to unveil more of its recommendations. But he also leaned on old ways of doing business, proposing his own task forces to study the contentious issue of integrating the specialized high schools.

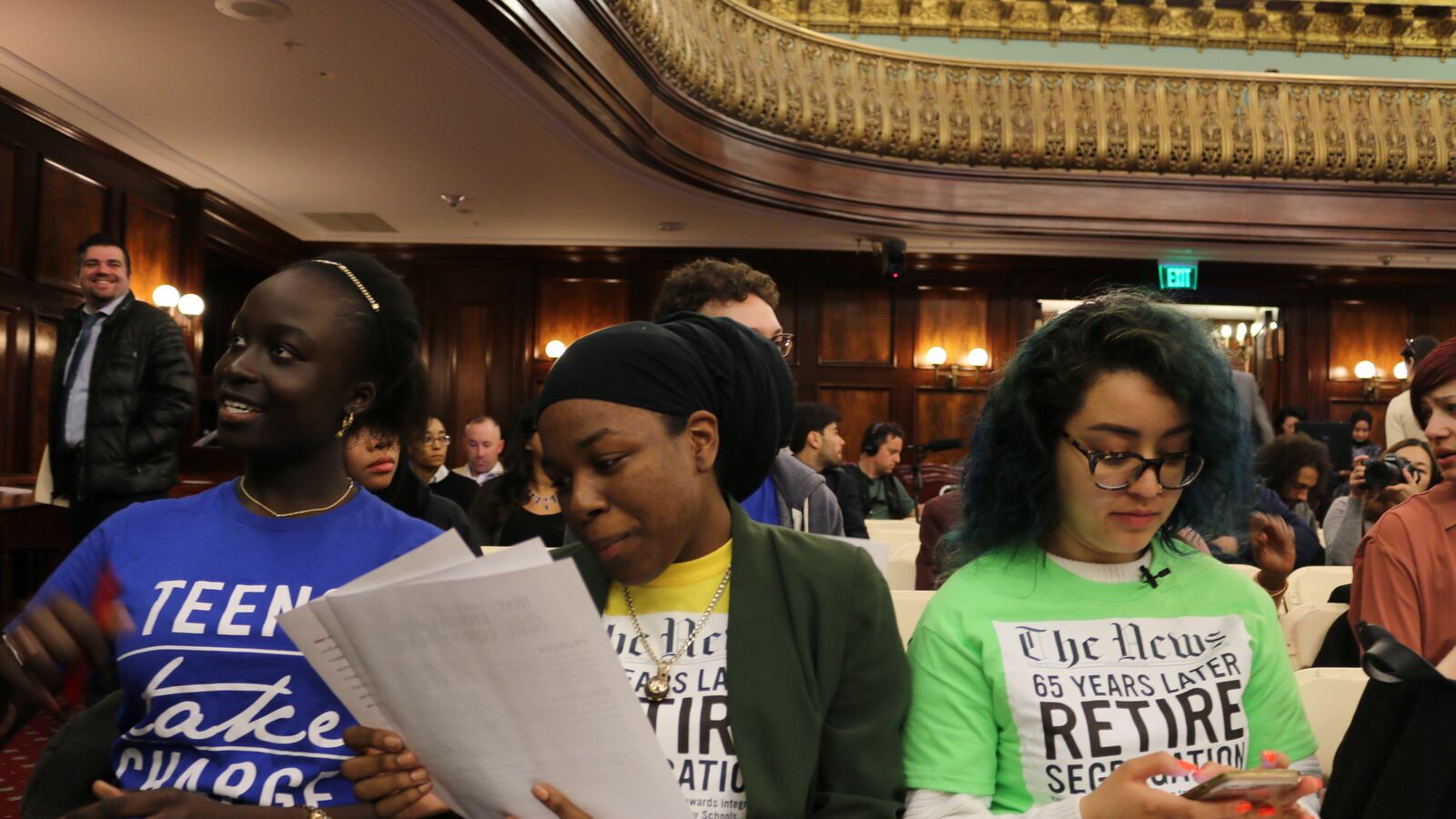

Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye, a junior at Brooklyn College Academy High School and member of the advocacy group Teens Take Charge, chastised the adults in the room.

“What are you going to say to me today? You need more time to study the issue? You need another task force?” she asked. “Let us address segregation today.”

Here are some other highlights from Wednesday’s hearing.

Potential changes for gifted admissions

Enrollment in the city’s gifted and talented programs is almost the reverse of city demographics, with white and Asian students, who make up roughly a third of the system at large, filling most seats. Most programs begin in kindergarten, and children have to take a test when they’re about 4 years old to gain admission.

Experts say that testing children so young is unlikely to yield reliable results and more likely a measure of financial advantage. On that point, Education Committee Chair Mark Treyger agreed, calling for unspecified admissions reforms.

Carranza hinted that the city is already looking at ways to change the process. He said the education department’s Chief Academic Officer is considering “more enlightened” ways to determine admissions, and also surveying what other cities do. He seemed to favor an approach that provides enrichment to everyone in the same classroom, rather than separating children by academic ability.

“What I’m not interested in doing is promulgating further segregation in our schools,” Carranza said. “I do think there is a role to play in creating enriched environments for students in every school — in every school — because every school has students who are on a spectrum of learning.”

But Peter Koo, who represents neighborhoods in Flushing, Queens, suggested things should stay as-is.

“We are all born with different talents,” he said. “You have to have G&T programs and you have to have the test.”

Any tweaks to gifted programs are likely to be met with fierce pushback, and de Blasio, who ultimately controls the education department, hasn’t shown any appetite for tackling the issue.

A new high school admissions method?

Carranza made waves when he described screens — competitive admissions standards used by many New York City schools — as “antithetical” to a public education system. Many blame screens for exacerbating segregation.

But Carranza said Wednesday that there are some “good” reasons to sort students.

When it comes to high schools that focus on particular themes such as the culinary arts, Councilmember Helen Rosenthal asked the chancellor whether it would be appropriate to ask why they’re interested in a school’s unique focus. Carranza said yes.

He appeared to be trying to find a way to allow schools to gauge a students’ genuine interest in different academic or vocational concentrations without requiring students to visit a school before applying. That approach was once part of a “limited unscreened” admissions policy that the education department recently eliminated because it could pose a burden for families challenged by transportation costs or inflexible work schedules.

Delay by committee

One of the most fiery exchanges was over the city’s School Diversity Advisory Group. The group, picked by the mayor, is tasked with putting teeth in the city’s diversity goals and plans.

The group’s first set of recommendations were released in February, and a second report on the thorny issues of admissions screens and gifted admissions is expected soon.

Treyger read a list of the group’s initial proposals and asked the chancellor whether the city supported each one. Carranza responded to each question by repeating that he thought the recommendations were good ideas but that he needed to discuss them with the group before committing to anything publicly.

Then Speaker Corey Johnson cut in.

“If you have the answers, and you know what the answer is, give the answer,” he told the chancellor. “It’s disrespectful to keep answering questions like that.”

What to do about specialized high schools?

Battle lines remained hardened around the what to do about the lack of diversity in the specialized high schools, a debate that overshadowed much of the hearing. Some council members tried to strike a delicate balance between the need for reforms and listening to the concerns of the Asian community, whose children make up a majority of the schools’ students.

Recent polling shows that most New Yorkers want to overhaul the single-test admissions system currently enshrined in state law. But before the hearing, a group of largely Asian-American advocates protested a city proposal to overhaul admissions.

One Asian-American student testified that her community shouldn’t be painted with a single brush and that she supported integration efforts.

“Integrating our schools will reduce racial bias and counter stereotypes,” said Bonnie Tang, who attended city public schools and is now in college.

Carranza touched on the undertones of the frequent argument that changing the admissions method would dampen academic quality.

“I will call that racist every time I hear it,” he said. “If you don’t want me to call you on it, don’t say it.”

Consensus around investments in schools

One rare point of agreement throughout the hearing: The city should do more to make sure black and Hispanic students get a strong education, starting early in their school careers. Positions on how to do that, however, once again varied — touching not only on arguments about gifted programs, but also on the need for more social workers, discipline reforms, and more teachers of color.

Education department officials repeatedly highlighted the city’s expansion of pre-K as an initiative that could help level the playing field.