This story was originally published on May 28 by THE CITY.

Complaints filed against the city Department of Education by parents of special education students have skyrocketed since 2014 — sparking a “crisis” that leaves some kids without essential service for months on end, a state-commissioned report found.

The flood of parents battling the public schools system for support is threatening to overwhelm a dispute-resolution system suffering from too few hearing officers and inadequate space to hold hearings, according to the external review obtained by THE CITY.

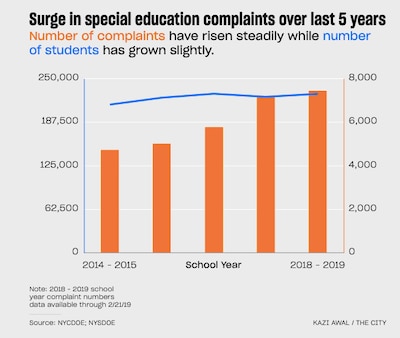

Complaints jumped 51% between the 2014-’15 and 2017-’18 school years, the report found. That surge has continued into the current school year, with 7,448 complaints filed as of late February — more than the total for the entire prior school year.

The average complaint was open for 202 days in 2017-’18, according to State Education Department data.

Growing complaints have caused a “crisis” that could “render an already fragile hearing system vulnerable to imminent failure and, ultimately, collapse,” Deusdedi Merced, of Special Education Solutions, wrote in a 49-page report obtained through public disclosure law and provided to THE CITY.

“That it has not yet collapsed is remarkable given the staggering numbers of due process complaints filed in New York City.”

One Family’s Struggle

Brooklyn mom Josie Hernandez, who visited the DOE’s impartial hearing offices on Livingston Street in Brooklyn last week, said she’s been fighting to get her now 14-year-old son the services required under his individual education plan — known as an IEP — since October 2017.

The legally binding document says her son should be in a classroom capped at 12 students, and receiving speech therapy and counseling. But Hernandez says her son has never gotten all three of those requirements at any of the four schools he’s attended.

A recent neuropsych examination determined the teen is three or four grade levels behind, according to Hernandez.

“For three years, they’ve not been giving him the services mandated on the IEP,” she said. “Right now, he’s in a class with 19 kids.”

Rebecca Shore, director of litigation for the group Advocates for Children of New York, said parents file complaints for a host of reasons.

Some students are placed into schools that don’t offer programs mandated on their education plans. Others are thrust into classroom settings that don’t match those mandated by the IEP. In some cases, services called for in the IEP simply are not provided.

“When the parents come to us, unfortunately, usually it’s at a point where it’s been three or four or five or six years [without services],” said Shore, whose group provided the external review to THE CITY.

“At that point, the student needs a lot of compensatory services to make up for the lack of instruction and appropriate instruction the student experienced for that much time.”

Tuition Reimbursement Cases Eyed

The report doesn’t attempt to identify why complaints are up. But it notes that some in the education field attribute the hike to a boost in parents using the due process system to seek tuition reimbursement for placing kids in private schools. That happens when the public school system can’t accommodate a student’s needs.

The number of students receiving reimbursement for private school tuition grew from 3,329 during the 2013-’14 school year to 4,431 in 2016-’17, according to the DOE.

The agency attributed the vast majority of complaint filings to tuition-reimbursement requests. Not all of those private school placements resulted, though, from due process complaints.

The DOE’s spending on the most common type of private school placement — known as Carter Cases — nearly doubled from $222 million to $417 million between the 2013 and 2016 school years, according to City Council budget documents.

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in June 2014 that the city wouldn’t be as litigious as the prior administration in dealing with parent tuition-reimbursement requests. The requests hit a high in the 2016-’17 school year, the latest figures supplied by the DOE show.

The de Blasio plan called for an expedited process for a majority of those cases, in which the city would decide within 15 days whether to settle. But advocates say the much-heralded policy sparked a volume of filings that overwhelmed city workers and made the 15-day deadline impossible to meet.

“A significant amount of time has been spent trying to get these cases to settlement, so that process can sometimes take six to eight months itself,” said Nelson Mar, a senior staff attorney at Bronx Legal Services.

He noted the root of the problem is that public schools simply don’t have enough services to cover the needs of many of the city’s 224,000 special education students.

New York City logged more due process complaints than California, Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania combined, according to 2016-’17 data collected by the state Education Department.

“The reason why you’re seeing these astronomical numbers is because they have never addressed the fundamental problems with their delivery of special education services,” said Mar. “There’s not enough programs and not enough staff to provide services.”

City Works on Changes

While the external review was completed in February, the State Education Department didn’t release it publicly and instead included it as an appendix to a “Compliance Assurance Plan” produced by state officials earlier this month.

That plan detailed how New York City was out of compliance with federal law for the 13th straight year on its delivery of services for special education students. Among the issues raised: mandated services on student IEPs not being provided.

One of the reasons the complaint process moves so slowly in New York City is because the DOE isn’t trying to resolve enough cases through mediation, the plan noted. There were only 126 mediations held last year, according to state data.

The compliance report highlighted a number of other failings within the complaint system — which is run by the city but overseen by the state. One issue: 122 hearings are scheduled per day on average and there are only 10 hearing rooms.

And the hearing offices are all in downtown Brooklyn, an inconvenient location for many parents, the state plan noted. Plus, parents have to navigate through a connected lunchroom that doubles as a space for teachers who have been reassigned after being accused of misconduct.

State officials gave city education officials until June 3 to file a corrective action plan, which must include boosting the number of staffers at the impartial hearing office and adding hearing rooms.

City officials said they’re already implementing many of the requirements, while they’ve asked the state to certify more hearing officers.

“We’re committed to improving the impartial hearing process for families, and we’re hiring more impartial hearing staff and investing an additional $3.4 million to add impartial hearing rooms and make physical improvements to the impartial hearing office,” said Danielle Filson, a DOE spokesperson. “We’re also hiring more attorneys to reduce case backlog as part of a larger $33 million investment in special education, and we’re supporting the state as much as possible to hire more hearing officers.”

DOE officials said they’ve already moved the reassigned teachers from the lunchroom.

State officials said they’ve been pleased with city Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza’s actions on special education thus far.

“We are encouraged by Chancellor Carranza’s commitment to make the systemic changes necessary to transform the way New York City supports students with disabilities and we have already started to see improvements,” said state DOE spokesperson Emily DeSantis.

This story was originally published by THE CITY, an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.