Summers can be tough for Bonita Bell, a mother from the Bronx with three children under the age of 10 trying to ensure her family has enough to eat. During the school year, she can count on free school meals to help keep her family fed. But over the summer, the meals can be much harder to access, owing to limited outreach and miscommunication by the city that is causing food — and federal dollars — to go to waste.

“I don’t think they’ve done a good enough job of letting people know what’s going on,” Bell said recently at a meal site at I.S. 177, where her children were picking up their free lunches for the day. “I knew because I asked around, but for most people it’s a word-of-mouth thing.”

The city advertises that it provides free breakfast and lunch from June 27 to August 30 at schools, parks, pools, libraries, and food trucks across the five boroughs to anyone under age 18. No identification or application is required to get a meal. An average of 7 million meals are served each summer, according to the city’s education department.

But the limited information the city puts out can be confusing and contradictory, and the system designed to help those looking for food can direct them to Westchester or even New Jersey, potentially leaving thousands of hungry children as meals go unclaimed — although once Chalkbeat raised the issue of the misdirections, the city’s education department appeared to correct it.

Last week, for example, less than 20 children showed up at a meal site in lower Manhattan, even as the borough’s president has launched a new effort to improve communication about the program.

Despite the no-shows, the need remains great. An estimated 348,500 children in the city live in households that are food insecure, according to Feeding America, a hunger relief organization. And the food insecurity rate for children in the city is nearly 11 percent higher than that for children nationwide, making the summer meals program vital to staving off childhood hunger.

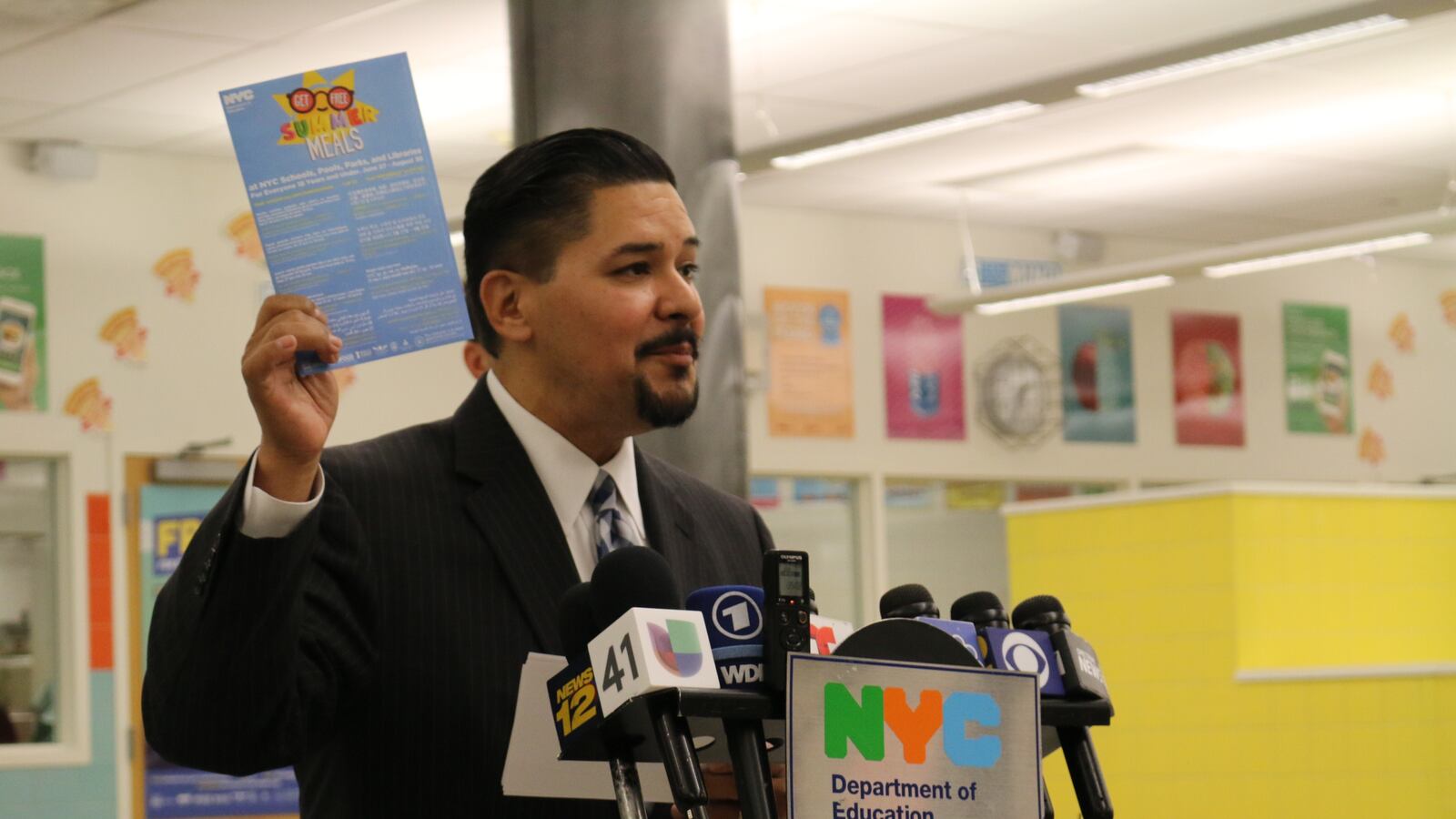

In May, schools Chancellor Richard Carranza touted the meals program in the Bronx, the city’s hungriest borough, according to Hunger Free America, where more than one in four residents — including more than one in three children — live with food insecurity.

“This is about taking care of our young people across the city and ensuring that they have access to free and nutritious meal options year-round,” Carranza said, brandishing a blue “summer meals” envelope containing information about the program in ten different languages — end-of-year material distributed to families before the summer break.

To find a neighborhood meal site, according to the envelope, parents can visit the education department’s online portal, text “NYCMEALS” to 877-877, or call 311. The department says there are 1,200 sites open throughout the summer, but acknowledges the website lists only 423 community-based centers. Of those, just 67 percent are open throughout the summer months. And many schools serving meals aren’t on the list at all.

“Obviously during the summer people are hungry, particularly children,” said Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer who has created a task force to improve the program. “It makes no sense for the city of New York to curtail the opportunity for people to eat and not more effectively get the message out to people that they can eat.”

And before Chalkbeat inquired, texting for more information about meal sites yielded seemingly random results. A request for locations in the West Farms neighborhood of the Bronx produced as top listings a high school in Yonkers and a Boys and Girls Club in Mount Vernon, both of which are in Westchester County. Searches in other boroughs led to advisories about food banks in New Jersey.

“We’re addressing some technical difficulties with our website and mobile tools so New York City students and families can more easily search for a site near them,” said education department spokeswoman Miranda Barbot. She noted in the first week of the program that the department had “served 100,000 more meals than last year.”

There’s also an app, which Bell, the mother from the Bronx, used to find her meal site, though she says it can be glitchy and difficult to navigate. Through the app, she learned that sites exist beyond schools. Once she did so, Bell told her friends and family, who were otherwise in the dark.

She said she wishes the city was doing more to help families like hers. “They’re home the whole summer, so it’s hard,” Bell said about feeding her three children. “To be able to give them a meal that I don’t have to make at home means I can save for another meal later in the day and on the weekends.”

Ida Ifill, who’s been bringing her and other children in the neighborhood to get free meals every summer for seven years, said she passes along information to strangers she sees on the street. Last year she and her youngsters walked several blocks every day before she found out through a friend that there was another food location right up the street.

She calls the program “a great service,” but added, “We have to let people know about it so people come, and they don’t shut it down.”

It’s that lack of communication about the program that Brewer is aiming to address. Her task force has gathered representatives from the department of education’s food and nutrition services and other city agencies to work towards better coordination and outreach.

“When you’re a parent, you’re not going to go check the department of education site, then the parks department, then New York City Housing Authority,” she said.

When Brewer first got involved, she said there was even less communication between the education department and families. To help fill that gap, her office has been producing its own flyers with information about the program and distributing them to schools, neighborhoods, and libraries two weeks before the end of the school year for five years.

Although the department of education is the face of the summer meals program and handles much of the organizing, meals are also served at pools, libraries, and housing complexes. However, before the formation of the task force, Brewer says, the education, health, parks, and housing departments weren’t working closely together.

“We’re still working on getting the agencies to work together, and there have been improvements,” she said. The task force plans to meet again in July to assess the first weeks of the program.

A practical reason for getting the program right, Brewer noted, is that it is funded through federal reimbursements. And if enough children don’t show up, the unserved meals get thrown in the trash.

“If we don’t utilize the program, we’ll essentially be leaving money on the table,” she said.

The city is also leaving food on the table. One of the meal sites Chalkbeat visited was forced to throw out meals after only 16 people showed up for food. They are expecting to serve nearly 300 meals a day as the summer goes on, according to one worker who didn’t have permission to speak to the press and wished to remain anonymous. The worker said they’re required to toss out meals that don’t get served.

At another site Chalkbeat visited, workers tried to give away meals to families in a nearby park rather than consign them to the garbage.

That any food is going to waste in a city with such a big child hunger problem is “indicative of the fact that there’s a lack of communication and outreach,” said Margarette Purvis the president of Food Bank for New York City.

Before the school year ends, Food Bank for New York City also works to raise awareness of the city’s summer meals program and encourages its soup kitchens around the city to serve as meal sites. They also run their own summer meal service at their location in Harlem.

“It’s so easy to just say the people who need it didn’t take advantage of it,” Purvis said. “You may have food, but did you have a plan for engagement?”

Every year, the city gets data on students who rely on free and reduced lunch, including their addresses and phone numbers. Purvis suggests the education department use that information to directly target families who are most likely to need summer meals. Her own organization uses data on the neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of food-insecure children for its Green Sidewalks program, which brings free, fresh produce where it’s most needed.

“We all know the address of poverty,” Purvis said. “That’s probably the easiest way to really ensure that we’re caring for all these babies who would be missing this great nutrition otherwise.”