In the wake of a string of anti-Semitic attacks in and around New York City, schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said Friday the education department is developing a new curriculum about hate crimes that will be rolled out next school year.

In the meantime, the nation’s largest school system said it will make available additional resources to teach about these crimes in the context of current and historical events.

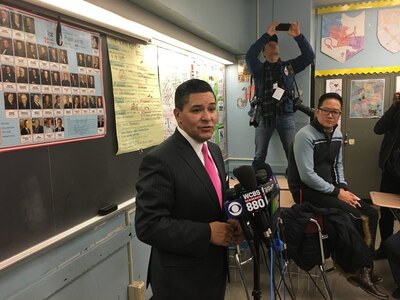

“We know that enlightenment starts in the classroom,” Carranza told reporters at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School in Borough Park, a Brooklyn neighborhood known for its large ultra-Orthodox Jewish population. “It starts with how do students learn about each other, how do they learn about other cultures, how do they make connections from what history has taught us to what is happening currently?”

As part of a broader set of efforts to combat anti-Semitism, city officials said they are implementing “hate crime awareness programming” this month at middle and high schools in Williamsburg, Crown Heights, and Borough Park, three Brooklyn neighborhoods that are home to large numbers of ultra-Orthodox Jews, many of whom wear traditional garb and speak Yiddish. In recent weeks, several members of these communities have faced alleged instances of verbal harassment and physical assault on New York City streets.

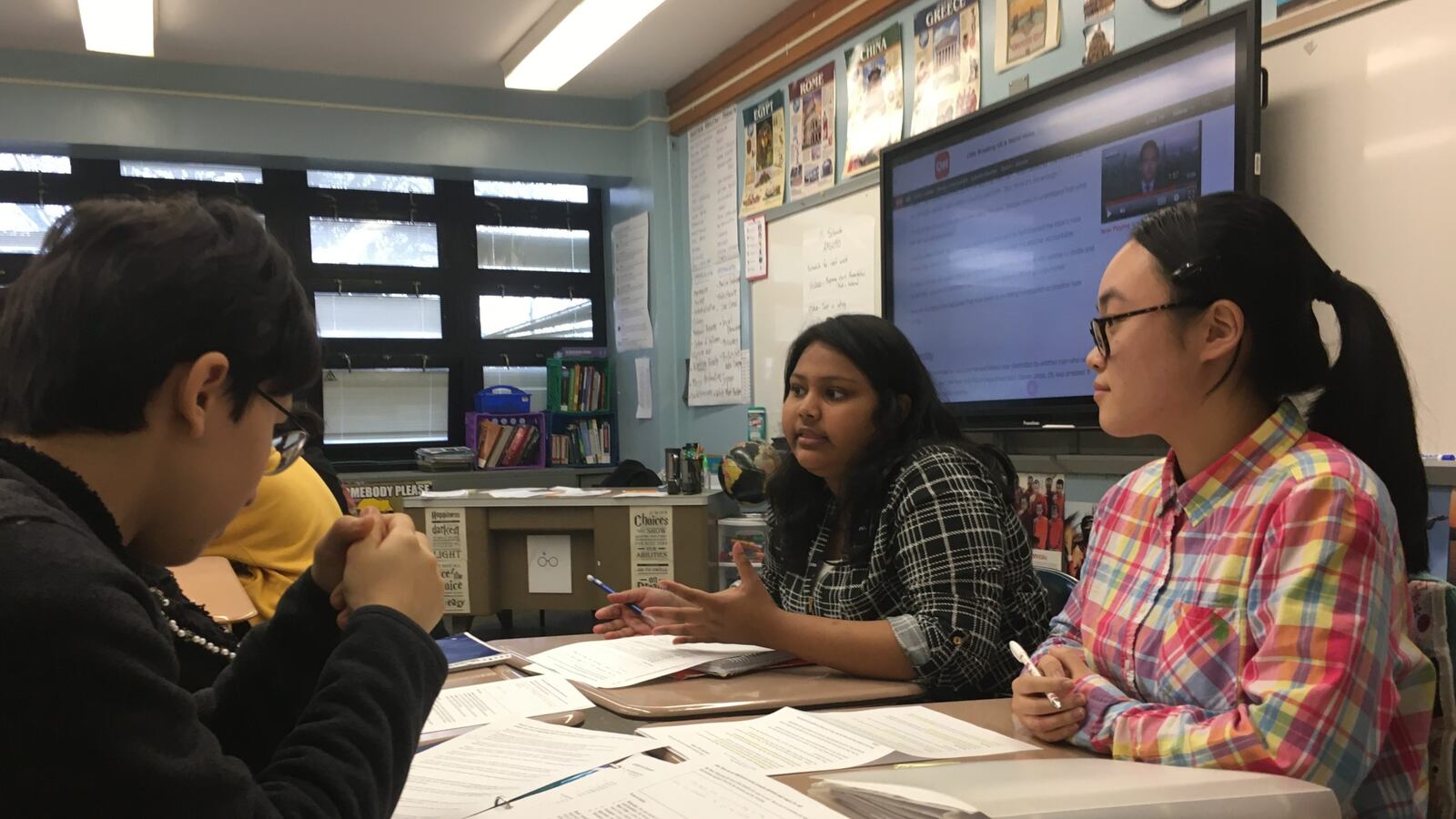

In light of recent events, schools are being encouraged to foster discussions about discrimination and religious intolerance “and collectively explore the positive actions they can take to promote acceptance, inclusion, and the diversity of their communities,” a department official wrote.

By next school year, schools throughout the city will also have access to “curriculum on hate crimes.” Officials said it will build on existing curriculums and “will focus on the concept of and occurrence of hate crimes and how they relate to historical events.”

Education officials said schools will not be required to use it, though state regulations mandate similar topics, including the Holocaust, be taught in middle and high schools.

The push for more programming in schools comes after the region has seen a spate of violence that has heightened anxiety among Jews across the city, from a Hanukkah stabbing at a rabbi’s home in suburban Rockland County, New York, last month to a mass shooting at a kosher supermarket in Jersey City.

In recent weeks, there have been a series of assaults that appear to have been directed at religious Jews in New York City; some of the assailants were reportedly teenagers. The New York Police Department has said there was a significant increase in anti-Semitic hate crimes last year.

The education department is also facing political pressure to ramp up education about hateful ideologies; on Friday, over three dozen city lawmakers sent Carranza a letter pushing for curriculum “around genocides throughout history” including the Holocaust.

Mark Treyger, who helms city council’s education committee, said it is not yet clear what the education department’s curriculum will look like, but said it should be prioritized citywide, not just in three Brooklyn neighborhoods.

“This is more valuable, quite frankly, than some of the tests our students are taking,” he said in an interview.

Even before the latest string of attacks, Carranza has said school curriculum should be more culturally responsive, arguing it can be a “matter of life and death” for some students. (Most members of the city’s various ultra-Orthodox Jewish sects send their children to private, religious schools, rather than to the city’s public schools — and the recent bias incidents have taken place away from schools.)

Department officials have said they are evaluating core curriculum offerings based in part on whether they include materials that represent students of different backgrounds, including race, socioeconomics, sexual orientation, and disability status.

During a press conference Friday, Carranza bristled at a question about whether there is research showing how long it might take for an expanded curriculum on anti-Semitism to deliver benefits.

“You don’t need a study to prove that if you teach kids about other kids, if you teach kids about other cultures, sorry to get passionate about this, this cannot be quantified in studies,” Carranza said. “If you teach kids not to hate, they’re not going to hate.”

There have been some studies on civics education and efforts to teach anti-Semitism more specifically. One study, for instance, found that students who visited a Holocaust museum were more likely to support protecting civil liberties and demonstrated deeper historical knowledge. However, there were also some unintended consequences: Those students were less likely to express high levels of religious tolerance.

Still, the researchers, Daniel Bowen and Brian Kisida, argue schools can act as an important lever for promoting civic values.

“We find that teaching students about the Holocaust, an extremely challenging subject for secondary school students, can play a vital role in the development of citizens who will protect civil liberties and defend oppressed populations,” they wrote.