About 100 public schools and 200 private ones in coronavirus hot spots will close Tuesday, one day sooner than Mayor Bill de Blasio had planned, according to Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

The schools in Far Rockaway, Southern Brooklyn, and Central Queens will close by end-of-day Monday. Also affected are about 100 pre-K sites and child care centers providing subsidized programs.

De Blasio had said schools will remain closed for at least the next two weeks, but Cuomo did not confirm that timeline, saying reopening criteria must still be established.

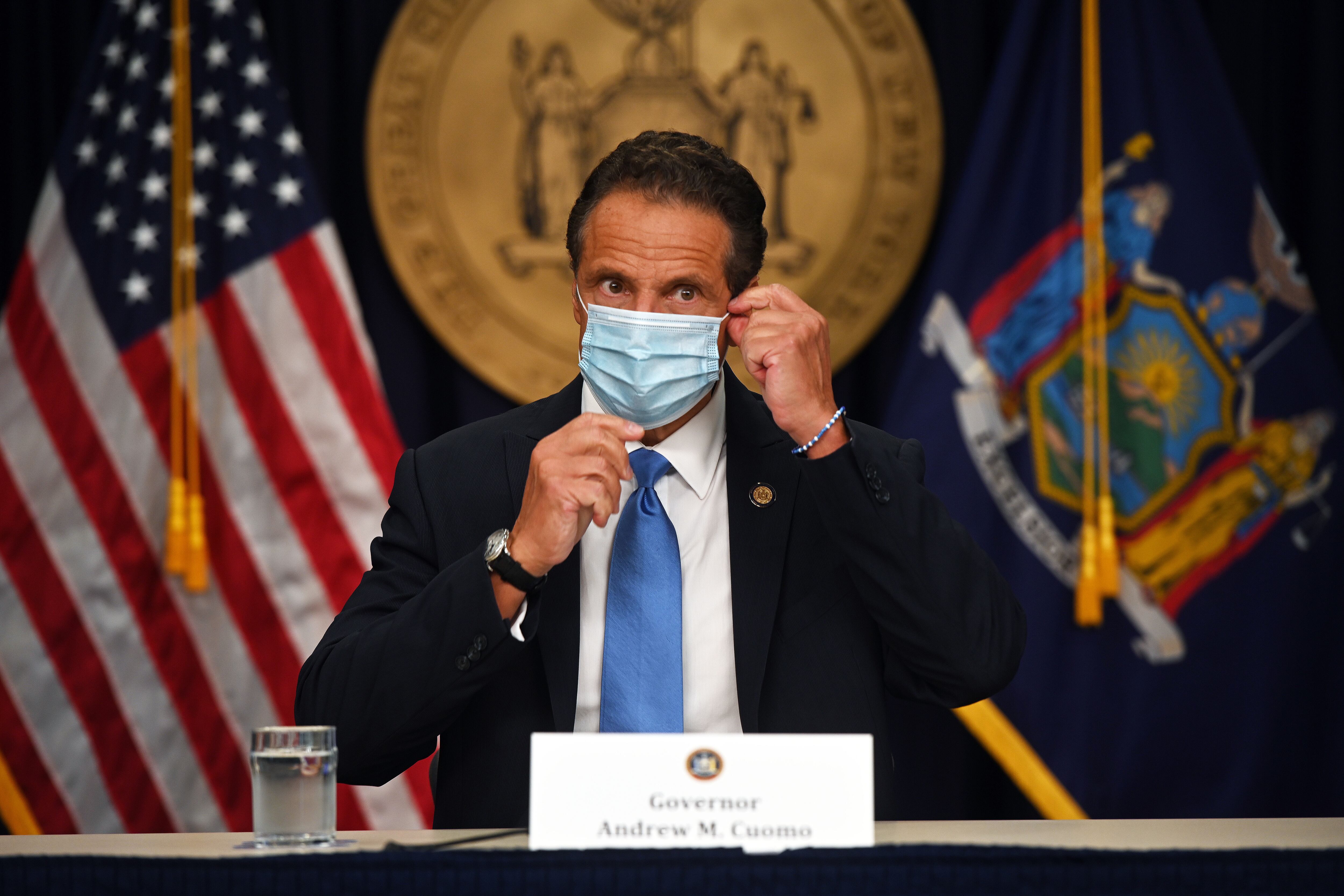

“I said to the parents of this state, I will not allow your child to be sent to any school that I would not send my child, period, and you have my personal word,” Cuomo told reporters, who said the state would ramp up enforcement of mask-wearing in hotspot communities.

About 82,000 students in city-run schools — a number bigger than the entire districts of Baltimore or Austin — are affected, according to enrollment data from 2019-2020. That does not include students enrolled in private schools, or in pre-K or child care centers that are subsidized by the city but independently run. Not all of those students had been attending classes in person. On Monday, those opting for fully remote instruction climbed to half of the city’s enrollment of 1 million students.

The closures are likely to throw off schedules and child care plans for thousands of working families who had chosen to send their children back to school for part of the week. It’s also a letdown for teachers and students eager to return to classrooms. But for others worried about a resurgence of the virus, they also come as a bit of relief.

Though school has felt safe so far for Jenn Colonna, who teaches kindergarten at P.S./I.S. 192 — nestled between the hotspot neighborhoods of Bensonhurst and Borough Park — she worried about traveling in and out of the neighborhood.

“I just feel like it was a matter of time before the rates started getting higher in the schools with the surrounding neighborhood rate going higher because the kids are neighborhood kids,” said Colonna, a union chapter leader, acknowledging that some kids are bused in from other neighborhoods.

Unless students or staff within specific schools tested positive for the coronavirus, the mayor previously said he had no plans to shutter individual schools. Rather he would only close schools citywide, and only if New York City’s overall positivity rate exceeded 3% over seven days.

But as positivity rates spiked in several communities over the past week, the city teachers union urged the mayor to close campuses in those areas. On Sunday, facing mounting pressure from the union, de Blasio sought the state’s approval for a plan to shut down schools and non-essential businesses. His proposal called for closing on Wednesday in nine ZIP codes where the coronavirus positivity rate had steadily grown past 3%.

Those ZIP codes include Borough Park, Gravesend, Homecrest, Midwood, Bensonhurst, Mapleton, Flatlands, Gerritsen Beach, and Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, and Edgemere, Far Rockaway, Kew Gardens, Kew Gardens Hill, and Pomonok in Queens.

On Monday, Cuomo approved de Blasio’s plan for the schools in those neighborhoods, but the governor said the closures should go into effect Tuesday morning.

Officials with City Hall and the education department did not immediately respond to questions about whether the city has a plan to provide child care to essential workers in the affected areas. This spring, the city hustled to open emergency child care centers inside schools, and more than 13,000 children signed up.

The governor did not order the closure of non-essential businesses until the state could find something more precise than a ZIP code to identify what should close. He also said businesses were not “mass spreaders,” as opposed to schools, even though there is no definitive evidence that K-12 schools employing virus safety measures are a significant spreader of the virus. De Blasio said he would move ahead with those business closures unless he hears directly from the state.

Many public health experts said New York City was in a good position to open schools safely, so long as schools took safety precautions such as requiring masks, social distancing, and proper ventilation. For weeks the citywide coronavirus positivity rate had hovered around 1%. Educators have for months raised alarms about whether schools will have enough personal protective equipment for staff and students, and whether buildings will have adequate ventilation as the city raced to perform repairs and upgrades.

Researchers are still working to understand how children transmit the virus. A recent study found that older teenagers are more likely than children younger than 10 to be infected with the virus and transmit it to others.

Cuomo — who spoke with de Blasio, Comptroller Scott Stringer, Council Speaker Corey Johnson, and teachers union president Michael Mulgrew shortly before his afternoon press conference — said he was concerned that coronavirus testing has not happened at all schools inside of hotspots. The city had planned to begin a random testing program at all schools this week.

Under that plan, New York City is expected to begin randomly testing 10-20% of students and staff at every school across the five boroughs, though separate testing protocols were being established for District 75, which serves students with the most complex disabilities. The education department recently backpedaled a rule that student testing would be mandatory and is now asking parents to consent to having their children swabbed.

Additionally, a recent study found that the city may need to test half of its students and staff twice a month in order to prevent outbreaks at schools.

Separate from the monthly testing program, city leaders have ramped up testing at schools in areas with rising positivity rates. As of Monday, testing will expand from eight schools a day to a dozen. That’s according to Ted Long, director of the city’s Test and Trace Corps, which helps track down close contacts of people who have tested positive for the virus so that those who have potentially been exposed can quarantine.

De Blasio wanted to wait until Wednesday to close buildings to give teachers time to help students prepare for virtual learning and hand out devices. That move prompted outcry from some educators and a city councilman, who said it didn’t make sense to wait.

De Blasio emphasized that there has been no evidence of community transmission inside of schools, but that the city was shuttering them along with businesses out of an abundance of caution.

He said the city is keeping a close eye on two other neighborhoods where positivity rates have been above 3% for five days straight. Those areas are ZIP code 11235, which includes Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and Sheepshead Bay; and ZIP code 11374 which includes Rego Park. If the numbers don’t go down, the mayor said those neighborhoods could face “greater restrictions.”

“We hope that pattern breaks literally today,” he said.

The mayor has proposed to reopen schools after two weeks if their communities show a coronavirus positivity rate that stays below 3% for seven consecutive days.

Observers have questioned how effective the plan to close schools will be in keeping positivity rates low, since many students and teachers who live in these targeted areas will still be traveling to schools outside of their home neighborhoods. Cuomo acknowledged that closing by ZIP codes was “imperfect,” and the state is working to find a better way to close communities.

The move to shutter the schools in the nine ZIP codes undoubtedly will be difficult for thousands of families, who preferred to have at least some in-person instruction for their children. A lot of research suggests that remote learning is not nearly as effective as in-person schooling, especially for children who already face the biggest challenges and disadvantages. It might also be a hardship for working families who need child care or those who struggle overseeing their children’s remote learning. The shift to fully remote instruction is also stressful for teachers who have been crafting in-person lessons and now need to ensure that their students will remain engaged virtually.

Colonna, the teacher from P.S./I.S.192, said staff held an emergency meeting Monday morning about how to best transition to all remote instruction without pulling students away from the teachers they’ve come to know over the past couple weeks. Staff raced to collect materials that both they and their students would need at home. The school sent out robocalls to parents Monday informing them of the closure and to come pick up extra instructional materials their children may need at home.

Because in-person and remote teachers had already planned to work closely together, figuring out a transition plan wasn’t hard, Colonna said. But she wishes the decision was made even one day sooner.

“Even [with] that one more day we would have been able to notify parents collectively, we would have been able to gather materials properly,” she said

Like several other high schools, Dewey High School in Gravesend scheduled all students to learn virtually, even if they chose to learn from the school building. The move, intended to solve a staffing shortage for hybrid learning, makes Tuesday’s transition somewhat easier for educators like Corey Brothers, an English as a second language teacher.

But he was also frustrated that the city and state did not decide sooner to close schools, and many students left Dewey on Monday thinking the school would close Wednesday, as de Blasio had proposed this weekend, he said.

Brothers was not looking forward to working from home again after doing so during the height of the pandemic last spring.

“The building provides a professional atmosphere for me to do my work,” Brothers said. “I hate working from home, where I’m so isolated.”

The closures won’t change much for Jen Walter’s family, even though her fifth grader’s Gravesend school is among those that will be shuttered. Watching the summer of chaotic back-to-school planning unfold, she chose to keep her son home from P.S. 216 — precisely to avoid a rough transition if schools were forced to suddenly close.

“A big reason why I chose 100% remote was consistency,” Walter said. “We won’t need to deal with that adjustment.”

Walter said she knows she is lucky that her family has the tools to navigate remote learning, with decent home Wi-Fi and enough devices. P.S. 216 has done an admirable job navigating remote learning, she added. But Walter wishes city leadership had spent more time training teachers and providing explicit instruction for elementary schoolers now learning how to create new files, attach them to emails, and submit assignments on new platforms.

“I don’t think that’s the school’s fault,” she said. “I think the mayor and chancellor got their priorities out of order.”