Manhattan high school senior Tiffani Torres started out in an AP calculus class this year with 35 students — one more than the uppermost limit high school classes are supposed to have under teacher union contracts.

It was overwhelming.

Students weren’t getting proper support, and four ended up dropping the course this spring, Torres said at a City Council hearing Friday focused on class size. She contrasted it with her experience at a small middle school where she felt like she could always go to a teacher for help and she didn’t have to worry about disrupting lessons with her questions.

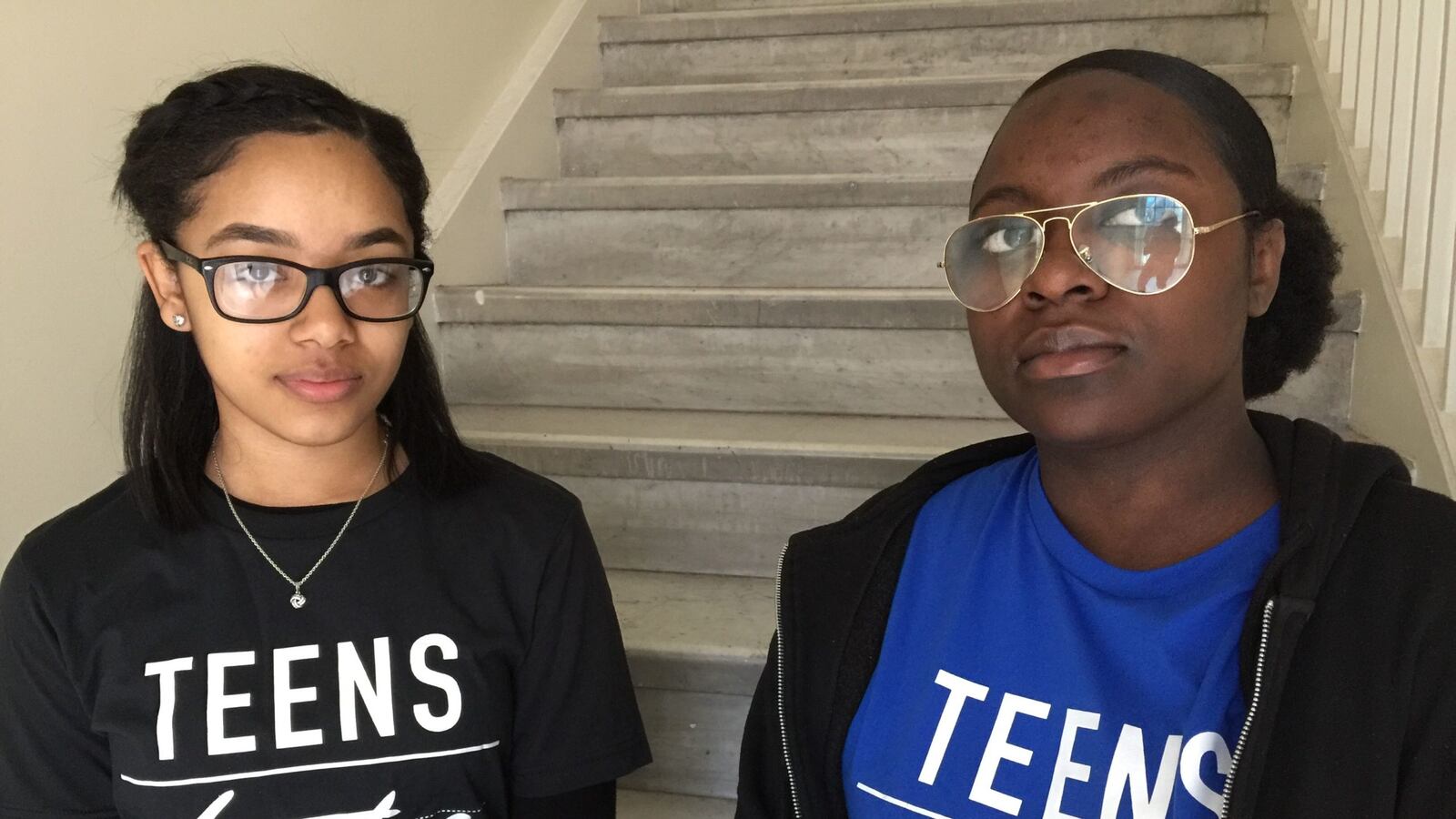

“When there are over 30 students in a room with a single teacher, all struggling yet unable to receive the attention they need, we begin to understand how black and Latinx students are consistently left behind,” said Torres, a member of Teens Take Charge, a student-led group focused on improving equity for the nation’s largest school district.

Bill de Blasio pledged to lower class sizes when he campaigned for mayor in 2013. But he never delivered on that promise. New York City classes remain, on average, 15% to 30% larger than those in the rest of the state. Classes are currently capped at 25 in kindergarten, 32 for elementary grades, 33 in middle schools (though it’s 30 for some of them) and 34 in high schools.

Nearly a third of New York City students were in classes of 30 or more students this fall, according to advocacy group Class Size Matters. The number of kindergarten classes with 25 or more has increased 68% since 2007, and the number of children in grades one through three in classes of 30 or more has increased by nearly 3,000%.

Many parents, educators and academics testified about the problems of overcrowding in schools — and ironically, many were barred from the hearing room because it was too crowded. Several blamed the class-size issue on the state for failing to live up to a decade-old court mandate to provide more funding to New York City.

Some pointed out that the city’s priciest private schools tend to have small classes, and public schools with powerhouse PTAs often fundraise for assistant teachers in the lower grades. Meanwhile, teachers in overcrowded classes with high-needs students can often miss important signs of dyslexia or other learning disabilities, parents and educators said.

Brooklyn City Council member and former teacher Mark Treyger said that he and many others left the teaching profession because large class sizes burned them out. That’s what happened to him when he had 34 students who were all English language learners.

“I think this is an issue that disproportionately affects a vulnerable population,” he said.

Although the state wasn’t fully funding the school system, he said, “at the same time, we can’t let the city off the hook.”

Class Size Matters called on City Council to earmark $100 million in next year’s budget to reduce class size, starting in the early grades and in struggling schools. The amount represents less than 0.3% of the education department’s $34 billion budget, noted Leonie Haimson, who runs the advocacy group. The group says it would pay for about 1,000 new teachers, and it could reduce class size in as many as 4,000 rooms.

The most influential study on class size was conducted in Tennessee during the late 1980s. The Student Teacher Achievement Ratio, or STAR, study randomly assigned students and teachers to a small class, with an average of 15 students, or to a regular class, with an average of 22 students. The achievement of students in the smaller classes translated into about three additional months of schooling four years later, according to Brookings.

Stanford’s Erik Hanushek, however, has challenged this study, noting research hasn’t proven academic benefits of class size reduction. He also pointed out that the study isn’t widely applicable, since most schools can’t get to 15 students.

New York City has never undertaken its own study on class size, Deputy Chancellor Karin Goldmark said, though she acknowledged that there is “strong” research showing the correlation between small class size and improved student outcomes. She also noted that teachers and families often cite class size as a top concern on annual school surveys.

“Do we wish class size was lower across New York City?” Goldmark asked. “We do. Do we think we can do that with the funding that we have? We don’t.”

Class size depends not only on the classrooms available, but also the education department’s ability to recruit and retain teaching staff, Goldmark said.

“It is also an issue of funding resources. It is important to note that the current budget outlook at the state and local level is very concerning,” she said. “Achieving class size reduction is contingent on funding, in particular from the state.”

The state has failed to fully fund a “sound, basic education,” as required by a New York State Court of Appeals decision in the Campaign for Fiscal Equity more than a decade ago, she said, saying the state owes the city $1.1 billion this year alone.

City officials said the administration allocated $640 million to reduce class size in the two 5-year capital plans under the de Blasio administration. The city’s schools with the highest concentration of poverty have an average class size of 23.8 while those with the lowest concentration of need have an average class size of 28.4.

Additionally, the current five-year capital plan provides $18.8 billion to create approximately 88 new school buildings and more than 57,000 seats, officials said.

But the city needs the money owed from the state to further reduce class size, Goldmark said. (The state disagrees with this interpretation and Gov. Andrew Cuomo wants to change the funding formula entirely.)

Goldmark is also a former teacher. Her first year, she taught a class of 36 students. Later in her career, she had a class of 18. There was indeed a “big” difference.

“I wish it could have been the reverse,” she said, explaining how she would have found it easier as a new teacher with a smaller class, and said that principals often make those kinds of decisions on the school level — when they’re able to.

The education department this year charged superintendents with responding faster to class size issues, since enrollment projections sometimes fall short of the actual number of students who register at many schools.

“You never quite know how many children you will have on the first day,” Goldmark said. “Every year we have more children in some schools and fewer in others.”