Class was in session Monday morning in New York City, even as school buildings were shuttered.

Teachers fired up laptops from their kitchen tables and living room couches. Students logged on to conference calls and video chatrooms. Parents reluctantly tried to teach fractions while cooped up at home.

Remote learning kicked off in the country’s largest school system with much anticipation, wracked nerves, a few technical snafus, and some pleasant surprises.

The moment required frenzied planning on the part of the system’s 75,000 teachers and their school leaders, who scrambled to distribute whatever devices they had on hand to ensure the city’s 1 million public school students could get online. Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said schools have distributed 175,000 laptops, iPads, and Chromebooks so far. For the thousands who still lack access, schools handed out printed packets of work.

It was the first of probably many days of digital teaching and learning. Campuses are slated to be closed through at least April 20, after spring break. But Mayor Bill de Blasio on Monday said it was unlikely school buildings will reopen this academic year.

Carranza said at a Monday evening press conference that teachers and students are “rising to the occasion,” but to expect road bumps.

“Today is day one of a new reality for the 1.1 million students and families in New York City,” he said. “The two operative words as we go forward are flexibility and patience.”

Here’s what the first day of (remote) school looked like for educators and parents on the front lines.

🔗‘I was incredibly heartened’: Nate Stripp, eighth-grade social studies teacher at M.S. 50

Brooklyn middle school teacher Nate Stripp logged on to Google Classroom Monday morning, surprised to see that all but two of the 18 students in his homeroom had marked themselves present.

“That’s better than homeroom attendance normally,” Stripp said, laughing.

Stripp, who teaches eighth grade social studies at Williamsburg’s M.S.50, offered his students a chance in the morning to video conference with him in case they had questions about assignments, or if they just wanted to chat. Fifteen students logged on, and he was again surprised: A few of his typically uncooperative students said they wanted to be back in school, and a few others had questions about how to complete assignments.

School leaders also held a schoolwide video conference, anticipating 15 students to join. Instead, about 100 logged on, reaching the allowed capacity for the meeting.

“I was incredibly heartened by the eagerness to work,” Stripp said.

He is in the middle of a unit on World War II and plans to stream live, virtual lessons to students on Tuesday and Thursday mornings.

In the afternoons, he will head to work at a downtown Brooklyn Regional Enrichment Center, where health care, transit, and emergency workers can send their children for care while they follow remote learning plans from their schools. Stripp volunteered because he’s healthy, young, and doesn’t have kids at home.

“It just made sense for me as someone with less to put on the table than a lot of my colleagues have,” he said.

It’s still too early to tell, but so far Stripp was “feeling OK” about virtual teaching. He previously used Google Classroom to post assignments and spent most of last week helping other teachers become familiar with the online teaching platform. He’s planned reading assignments for students through Newsela, which provides articles at five different reading levels. That’s important, he said, because his school’s students are diverse in their abilities — he estimates that about a third of his students have individualized education programs, and a third of them are learning English as a new language.

Leading up to Monday, teachers at his school drove around Brooklyn to drop off Chromebooks they already had on hand to any families in need. M.S.50 is a Title I school, which receives extra federal money because it has a large portion of low-income students. Many students there don’t have computers or WiFi access, he said.

Across the city, the education department aims to distribute about 25,000 internet-enabled iPads this week to students who have no access to technology.

“We know the DOE is planning to provide stuff, but how quickly those iPads are going to be rolled out is really up in the air,” Stripp said. “Last week, we wanted to organize and make sure kids have something to start.”

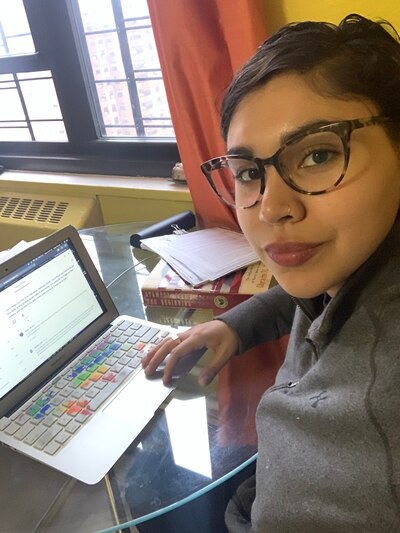

🔗‘I was terrified when I woke up’: Naomi Peña, mother of four on the Lower East Side

On the first day of remote learning citywide, Naomi Peña woke up to 25 notifications from her 10-year-old son’s classroom teacher, who was busy uploading digital assignments, unwittingly deluging parents’ email.

“I was terrified when I woke up,” Peña said. “I was completely overwhelmed.”

Her 10-year-old daughter’s teacher, by contrast, made sure each child had an email account, access to video tutorials, and detailed color-coded schedules for parents to follow, including assignments that should be completed on a given day (labeled in pink).

The twins attend the same school, but their classroom teachers have varying comfort levels with technology. “My daughter’s teacher has got it together,” said Peña. “My [10-year-old] son’s teacher is not there yet — everyone is learning from each other.”

Peña, a mother of four who works as an administrator at a tech company, said the schools have generally been helpful in preparing for the transition. Her seventh-grade son’s school trained parents to use Google Classroom, and Peña has received multiple phone calls from their schools to check in and make sure she feels supported.

“Oftentimes you feel like you’re alone in this process, but every single teacher called me and, if they didn’t get a response, they called again,” said Peña, who is also a parent council leader in Manhattan’s District 1. So far, her children’s coursework mostly involves assignments that can be completed throughout the day and don’t require logging in at an appointed time.

Despite that support, Peña is still nervous about morphing from parent to homeschool teacher. Two of her children have dyslexia and one of them receives more structured reading instruction and math tutoring at programs outside of school multiple times a week; now those programs are indefinitely on hold.

Two of her children also receive extra services including speech and occupational therapy. Her children’s therapists have been in touch to continue those services virtually, but it’s unclear when they will begin, Peña said.

“I wasn’t trained in these skills that these other professionals have to help him,” referring to her 10-year-old son.

She’s also worried about what happens if closures stretch for the rest of the school year. “Are we going to have to invest an entire school year on catching kids up?”

🔗‘I miss my students’: Noah Garcia, sixth-grade English teacher at M.S. 447

Noah Garcia spent much of her morning answering a steady stream of questions coming in from her sixth-grade students at M.S. 447 in Brooklyn.

In a thread of about 90 messages in Google Classroom, the students from her English class wanted to know how to edit their responses and whether they could move on to a new assignment. Some just posted to say that they missed their classmates. “I don’t know if we anticipated all of our students to get on at the same time but it definitely worked out that way,” she said.

The English department at M.S. 447 is easing its students into online learning. Day one was a review of expectations now that classes are online, and what each day’s schedule would look like. By 2:45 p.m., almost all of Garcia’s students had submitted their assignments for the day.

For those who didn’t, Garcia planned an early evening phone call to nudge them along. It’s not about giving failing grades, but about checking in with students and families, she said. Her school plans to be as flexible as it can.

“If a student reaches out and says, ‘Hey my WiFi is choppy,’ or, ‘My parents are online,’ then we’re going to be understanding,” Garcia said. “We still want them to learn and not be deterred from getting online.”

Garcia, who teaches classes that mix students with disabilities alongside general education students, spent the past week in a mad dash of preparations. She collaborated with her colleagues to create slideshows, add recorded audio to lessons, and reach out to students who have disabilities and might need reading materials that are on a lower grade level or narrated by a teacher, among other accommodations.

“I think it’s really important to recognize in this time how hard teachers are working and how emotionally invested teachers are in these students,” Garcia said.

Though the lead up to Monday was a blur, there were moments when the emotional toll of having to leave behind her classroom began to set in. It hit her as she went to the library alone and hand-picked books based on her students’ tastes to send home, and again when she realized she’d have to bring home the class betta fish, Elmo.

“It’s unexplainable. We don’t know if we’re going to go back to school,” she said. “I miss my students.”

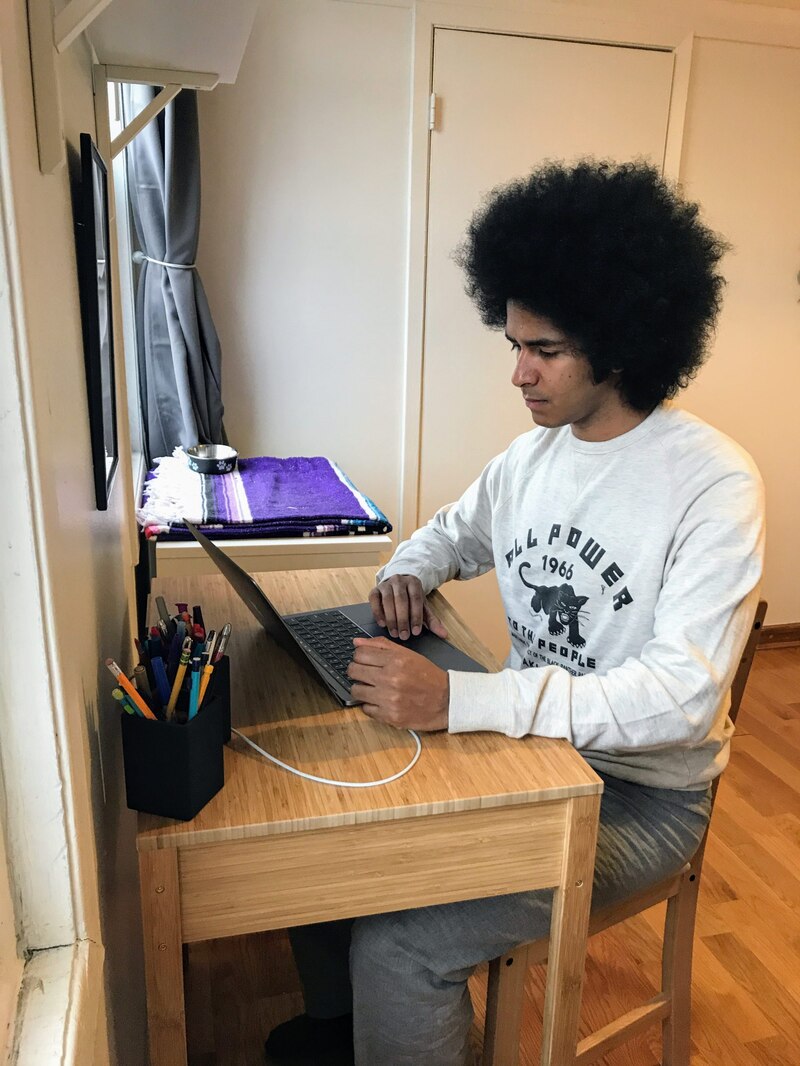

🔗‘We have to kind of improvise’: Ronnie Almonte, biology teacher at Edward R. Murrow High School

Biology teacher Ronnie Almonte is trying to teach his students about gene expression, but he is having them submit answers to questions using Google Forms instead of pencil and paper.

“In some ways, it’s not so different from what I’d do in the building,” said Almonte, who teaches at Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn.

He largely spent the day devising assignments, uploading them to Google Classroom, and reviewing student work. For an AP Biology class, he reviewed changes to the exam, which can now be taken online and has been shortened to 45 minutes.

Almonte is still expecting his students to complete regular assignments that take between 30 minutes and one hour, and he is planning to hold virtual office hours for students who have questions or need more direction. He hopes what they turn in can be graded pass/fail, but has not yet received clear grading guidance for online learning.

“Everything has been thrown at us, and we have to kind of improvise,” he said.

Almonte is also concerned about what the shift to online learning will mean for his students, especially those with disabilities. He teaches a freshman integrated co-teaching class — with two teachers and a mix of special education and general education students — and is worried that students who need help understanding assignments will struggle.

“It’s not the same as being in class and having that dialogue,” he said.

And he’s also hoping for answers soon on whether he should still be preparing his “living environment” class to take the Regents exam with the same name. State officials have canceled standardized tests for students in grades 3-8, but have not said whether the Regents, a state graduation requirement, will continue as planned this year.

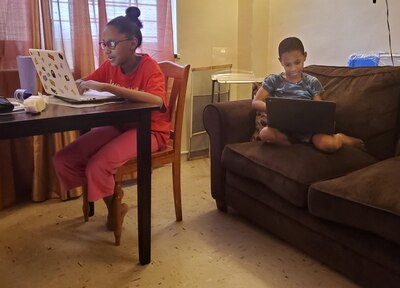

🔗‘This online thing, it’s not working’: Magdalena Garcia, mother of two in East Harlem

The school day got started late in Magdalena Garcia’s East Harlem home. Her two children — a daughter in fifth grade and a second-grade son — slept in and didn’t log into their laptops by 9:30 a.m., as their teachers had asked.

Garcia said she struggles with depression and panic attacks, expected it to be hard to homeschool. On Monday, she learned just how hard.

“They have their own separate schedules, with different things to do at different times,” she said. “I’m going to be honest: I couldn’t keep up.”

For her son, Garcia has to help navigate multiple online programs, like Zearn and Brain Pop. Her daughter is trying to learn fractions by emailing and messaging her teachers.

“Even though the lines of communication are open and she’s able to ask the teachers the questions she needs, it’s still different than face-to-face,” Garcia said, noting her daughter has been struggling with the day’s material.

She’s worried about her children being held back — especially her daughter, who is supposed to head to middle school next year. Garcia said she lost steam after just a few hours of online classes and plans to ask their teachers for printed packets of work instead.

“It has nothing to do with the teacher. It has to do with the way my children learn,” Garcia said. “And this online thing, it’s not working for them. It’s not working for me.”

🔗‘It was nice to see how excited and engaged my students were’: Stephanie Edmonds, 10th-grade global history teacher at Bronx High School for Law and Community Service

On Monday, high school teacher Stephanie Edmonds started a new balancing act. She woke up at 6 a.m. and posted the day’s assignments to Google Classroom for her sophomore Global History students along with explainer videos. Then she turned her attention to her 4-year-old son, who would usually be in a pre-K class.

They played educational games for a few hours, until his nap time at 1 p.m. A half-hour later, it was time for Edmond’s first official Zoom session, open to all 65 of her students. About 25 people logged on for the extra-credit session focusing on the coronavirus pandemic, which walked students through an assignment that is due tomorrow.

There was one hiccup. A few students used unidentifiable user names in Zoom and typed swear words in the chatbox, she said. She booted them out and wants to require students to identify themselves properly tomorrow to discourage acting out.

For the most part, the session went well, she said. Even her students who were too shy to turn on their cameras were using the chat to share their thoughts. Edmonds thought she and her co-teacher had the same teaching rhythm they have in person.

“It was nice to see how excited and engaged my students were in wanting to participate,” she said. “We’ll see at the end of today how many students got in their assignments.”

She plans to check in on students who don’t submit their lessons on time, not to “punish” them, but to see if they need help or if they had trouble accessing Google Classroom. Now that some of her students are home, they’re also spending time watching younger siblings — some of whom made a guest appearance on Monday’s Zoom session, she said.

Edmonds was also in touch with a few students who had not yet checked into Google Classroom since last week. One of them told her that she didn’t have internet access for her school-issued laptop. Edmonds told her about the 60-day free WiFi options from Spectrum and Optimum but hasn’t heard from that student since. If she doesn’t hear back soon, Edmonds will turn to a school counselor for help.

That’s why Edmonds thinks that constant communication will be key.

“Reaching out to the kids who didn’t turn anything in, making sure they saw the assignment, making sure they understood it,” Edmonds said. “I don’t want them to get two days behind.”

🔗‘When you have lemons, make lemonade’: Anthony Cosentino, principal of P.S. 21 in Staten Island

For all the uncertainties of the last two weeks, Monday felt like a good day to Anthony Cosentino, principal of P.S. 21 in Staten Island.

Students were meeting teachers virtually. Teachers have offered one-on-one appointments to students so they can connect and offer feedback. Cosentino spent the day checking in with teachers, paraprofessionals, and other support staff and peeking into some of the video conferences that teachers were holding.

He heard from parents and even a couple of students who liked the instructional videos that were posted to Google Classroom.

But as he’d expected, there are some kinks to work out. Teachers were working “tirelessly” to help families troubleshoot a variety of issues — whether it was signing in or getting familiar with the online learning platform, he said. Many families had never used it before, and P.S. 21’s youngest students, such as kindergartners, need their parents’ help to access the program.

He said the school provided tutorials on their website and on social media, in both English and Spanish. Still, learning the platform takes time, which might be a scarce commodity for parents.

“If you have two working parents who are supporting one or more children in remote learning at home, it’s really challenging, right?” Cosentino said.

He believes that with time, “trust and patience,” families and students will get used to it. And if schools are closed past April 20, Cosentino said he expects his students to become well-versed in it.

Despite the troubleshooting, families, teachers, and children have said they like Google Classroom and “want to move forward” with it, he said.

“That was something really nice to see — using the cliche, when you have lemons, make lemonade,” Cosentino said.

This article answers questions raised by our readers. Share your coronavirus-related questions, concerns, and ideas by emailing us at community@chalkbeat.org, and keep up with our reporting on COVID-19 here.