Rosario Gonzalez, a 91-year-old paraprofessional who cared tenderly for children in an East Harlem special education program, rarely missed a day of work in more than three decades.

Claudia Shirley continued to teach in Bushwick even after retiring, and loved her job so much that she inspired her two daughters to become educators themselves.

Carol King-Grant, a special education teacher in the South Bronx, was known for her love of sudoku and beautiful singing voice.

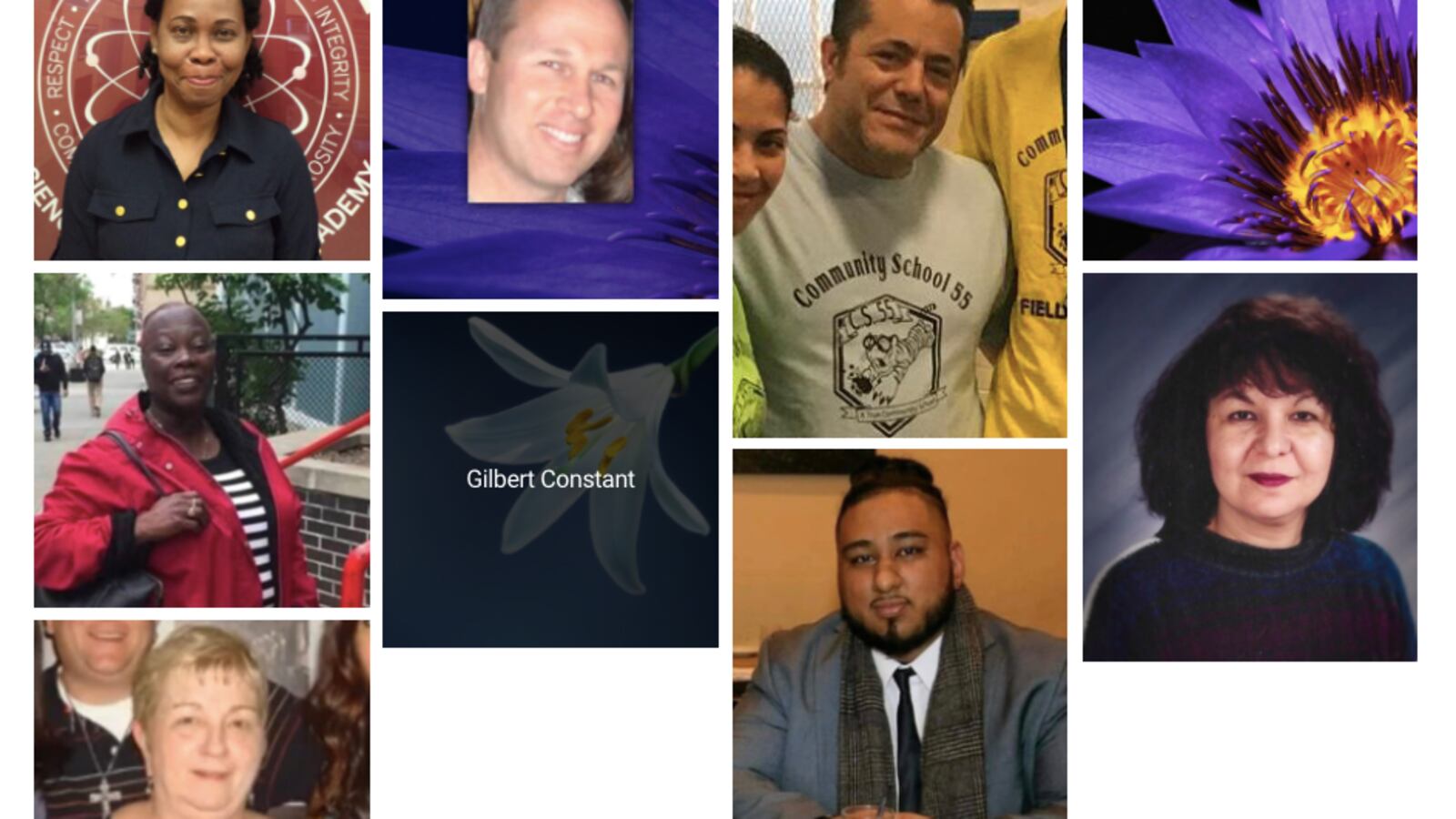

All died in recent weeks from suspected cases of the coronavirus, according to the United Federation of Teachers. The union announced that, as of Friday, it knew of more than 40 of its members presumed to have been claimed by the pandemic, including both active educators and retirees.

The union is naming names, and releasing a tally of the lives lost at a time that the education department has refused to do so. The department’s silence has sparked an uproar among teachers, who feel the lack of recognition is a smack in the face, particularly as they continued to report for work even after the danger of COVID-19 was well known.

Deaths of union members are typically tracked, whether related to the coronavirus or not, to ensure that survivors receive the benefits they’re entitled to. On Friday, President Michael Mulgrew said the union and its national affiliate are lobbying to ensure that families of victims have their insurance costs covered in the next federal recovery bill.

The union’s count of coronavirus-related deaths is based on reports by family members. It provides a glimpse into the virus’s toll on the country’s largest school system and one of its largest workforces. There are about 75,000 teachers in New York City, with the ranks swelling to about 200,000 including retirees and other members.

The union is collecting the stories of members who have passed on a new website, honoring their lives virtually while the threat of the virus prevents mourners from coming together in person.

Additionally, at least two school administrators have passed away. Mark Cannizzaro, president of the union that represents school leaders, said the education department “should release the names of those lost and should publicly honor each individual for their service to the City.” He added that the union also supports efforts to extend benefits to families “of those who die while in service.”

The education department has kept mum on the number of cases within its ranks even as other public agencies, including the police department and transportation authority, have released figures. However, the education department stopped confirming cases as community spread became rampant and the health department told New Yorkers to assume they have been exposed.

“We understand there is a lot of uncertainty across the City surrounding COVID-19,” education department spokesperson Miranda Barbot told Chalkbeat on April 2. “School employees are sometimes reporting information to their principals and superintendents, and we are determining how best to collect this information in one place.”

Teachers have demanded that the city publicly disclose deaths among their colleagues. In the absence of official information about the disease’s spread within school communities, teachers have taken it upon themselves to inform their co-workers of positive cases. They have blasted the city for keeping campuses open even as the number of sickened New Yorkers skyrocketed.

Union records show that principals are required to log cases of suspected coronavirus diagnoses by writing to an education department email address and contacting the health department, and filling in a separate education department database.

Schools chancellor Richard Carranza has sometimes acknowledged deaths publicly — but without disclosing identities. He said “it’s a little more complicated” to know the true numbers within the education department and also balance the need for privacy than other public agencies.

“We have to respect and recognize the wishes of families during these trying times. Some families don’t want us to publish the names of their family members who have been affected by COVID-19,” he said at an April 2 press conference. “So we want to respect the wishes of the families, but we also want to be transparent as much as possible.”

Brooklyn City Councilmember Mark Treyger, who chairs the education committee, has said he is considering legislation that would require the city to release information regarding cases of COVID-19 among educators.

“Still no transparency available to educators and school families. The buck stops at the top and City Hall needs to release” figures, Treyger recently tweeted.

Separately, the union is advocating in Washington for the next recovery bill to cover insurance premiums, as families may lose coverage after their loved ones die.

“The pandemic has already left dozens of families of UFT members without a major breadwinner. At the same time, tens of thousands of New Yorkers are now out of work,” Mulgrew, the union president, said in a joint statement with the national American Federation of Teachers. “The federal government needs to step in to ensure that deaths or job losses don’t also mean the loss of family medical coverage.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story reported that Anton Updale, a Staten Island teacher, had died due to the coronavirus. He is included on the teachers union coronavirus-related memorial page, but the cause of death was not immediately clear on Friday, according to his school’s principal.