This is part of an ongoing collaborative series between Chalkbeat and WNYC/Gothamist reporting the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on how New York students learn and on how educators teach.

Five weeks after New York City moved to remote learning, 19,000 students who requested devices still don’t have them. The education department has pledged to deliver them by the end of the month.

Department officials and educators have been mobilizing to fill the technology gap — mailing hard copies of assignments home, dropping off 175,000 devices that schools already owned, and distributing 231,0000 of 300,000 newly purchased iPads since online learning began.

Despite that massive mobilization, big challenges remain. The department is still working to ascertain the true number of students without devices. Many students have gone weeks without consistent access to schoolwork and have slipped further behind their peers. Even families who are now getting devices might have difficulty getting up to speed using them. On top of that, many low-income families may be dealing with food insecurity, job losses, and disproportionate health impacts of the coronavirus.

Six-year-old Dakari Bolton, a kindergartener who lives in a Manhattan shelter, did not receive an iPad from the education department until last week — more than a month after his school shut its doors — even though officials said they prioritized students in temporary housing for devices.

“It’s beyond frustrating,” said Keyshawn Woodbury, Dakari’s mother, noting that he receives special education services that have not completely resumed. “I want him to keep the writing up and to learn the letters.”

Though five of Dakari’s siblings received iPads, Dakari relied primarily on a paper packet of work his school sent during the first week of remote learning. When he exhausted that packet, it took days of back-and-forth communications for his school to create and send a new one.

Even then, the updated assignments weren’t easy to obtain. The school sent the worksheets to one of the education department hubs that are still open for the children of essential workers, Woodbury said, a significant walk from their shelter and out of reach.

“It’s just a lot — you’re fighting with the [education department], you’re fighting to keep a roof over your kid’s head,” Woodbury said, adding that her son’s education is “at a standstill.” She’s struggling to help her other children, too. Woodbury is not sure how to check whether they are getting assignments on their iPads.

Department officials said the delay in Dakari’s iPad was due to a data entry snafu.

The bulk purchase of iPads comes as Mayor Bill de Blasio has proposed cutting hundreds of millions of dollars from the education department’s budget amid the coronavirus pandemic. The total cost of the 300,000 devices is just over $269 million, including three months of unlimited internet access.

The department received about $42 million in discounts on the devices, cases, and internet plans and may be eligible for federal funding to help cover the cost, officials said. It comes out to about $897 per device, including the case, internet, and a three-year warranty.

“We have always said that despite financial hardships we will not spare any resource needed for learning, and we decided on iPads because Apple could commit to producing devices on a large scale in a short time frame and give students connectivity without Wi-Fi,” Miranda Barbot, an education department spokesperson, said in a statement.

It’s likely that thousands more students, who may not have initially requested devices, still need them. “We still think there are kids out there who need help and we don’t know,” de Blasio told reporters. “We’ve asked school administrators and teachers to identify any families they think may not have a device and reach out and confirm whether they do or don’t.”

[Related: Grades, attendance, devices: What you need to know about remote learning in NYC]

Many families assumed that schools would only be closed for a few weeks and figured they could rely on smartphones as a stopgap or didn’t realize they could request a device for each child, observers said.

“I don’t think the need has been satisfied by any means,” said Rachel Forsyth, who helps supervise school programs for Good Shepherd Services, a non-profit that partners with dozens of city schools. Last week alone, Good Shepherd distributed 400 laptops to students that the organization bought or were donated.

Distributing laptops isn’t just about giving students access to online learning — it can also help families locate the nearest food bank or simply give students a way of connecting to their peers and stave off feelings of isolation.

“That need for connection and belonging and being in a space with other people who you know care about you is just huge right now,” said Forsyth, whose organization has also been providing a lot of technical support to families on how to use devices.

Skylynn Lozada, a senior at West Brooklyn Community High School, struggled to complete schoolwork for weeks as she shared a single smartphone with her brother.

“It was really hard to do school work and stay focused,” she said, recalling an economics essay she tried to type out on her phone, only to realize later she was far short of the 15-page length requirement. “It’s a little screen, everything is set up differently from how it would be on an actual laptop.”

Lozada got some relief after her principal delivered one of the school’s laptops to her doorstep a couple weeks after remote learning began. But she and her brother are still relying on her smartphone for internet access, which frequently runs out of data.

She also worries about staying motivated amid all the upheaval. Her father, a construction worker, lost his income. Even though Lozada’s high school is an alternative program that specializes in serving students who have fallen behind at traditional schools, she is nervous about completing all her work.

“I wake up, and I dread it. I don’t want to stare at a screen all day,” she said. “I’m going to try to do it, but my motivation is just slowly not there.”

To help make sure students like Lozada don’t lose access, some educators have built mini logistics operations of their own.

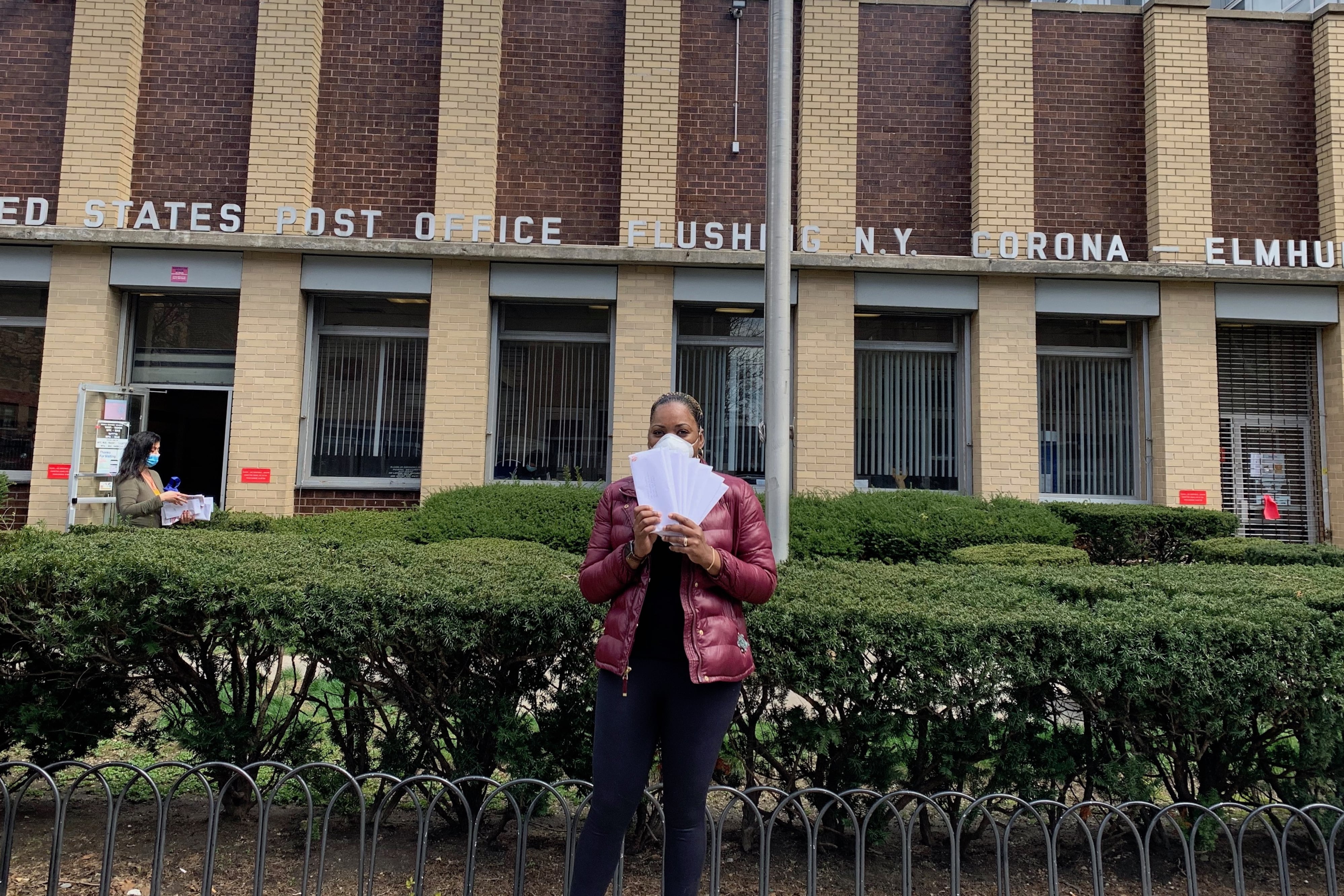

Queens teacher Monique Lee has been mailing out paper packets to students every week for the last month. She estimates that about a quarter of students at the High School for Construction Trades, Engineering and Architecture didn’t have a device when her school building shut down.

“I found out which kids we hadn’t been hearing from, and I thought, ‘Hey, old school mail always works,’” Lee said.

She makes a trip to the post office on Thursdays and said students snap photos and send her pictures of completed worksheets. “The biggest obstacle is me wearing my N95 mask while my glasses get fogged.”

In Brooklyn, M.S. 88 science teacher Lynn Shon has amplified her students’ need for devices on social media with links to a Google spreadsheet — and has had success matching her students with donated computers.

But as her efforts have expanded to other students in her school, it’s begun to feel a bit like whack-a-mole.

“I got a device for a student only to find out he had three siblings who didn’t have one,” she said. “Multiple school age children in a household with one device is a big barrier as well.” She said she has now matched 33 students with devices and continues to field requests.

“I don’t want to send the message to the world that it’s the responsibility of the teacher to be a social worker, to be the tech provider. But I can’t watch my students not participate in school because they don’t have a device,” she said.

“We’re all searching for comfort right now, and for me, comfort comes from knowing I’m doing the best I can.”

Reema Amin contributed