Whenever New York City is ready to begin reopening its economy after months of sheltering in place, child care will be essential for families returning to work. But independent preschools like Andre Farrell’s warn they might not be able to hold on that long.

Just three weeks after preschools and daycares were ordered to close as the coronavirus pandemic engulfed New York City, Farrell hit a financial wall. The director and owner of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Katmint Learning Initiative had no choice but to permanently shut down two of his three schools.

Katmint quickly shifted to online classes, but many families had logged off. The program is serving fewer than half the typical enrollment and Farrell has slashed tuition.

Child care in New York is a $4.2 billion industry, just over a third of which is supported by public dollars. While fundraising campaigns for restaurant workers and other sectors have grabbed attention, preschool programs say their struggles as small business owners has gone under the radar.

Many pre-K centers feel like they’ve been left to fend for themselves to keep their staff paid and, for those who manage to stay afloat, figure out what it might look like to finally reopen. They are turning to each other for help: The leaders of about 50 centers and schools have banded together to create the Brooklyn Coalition of Early Childhood Programs, a new advocacy group that is fighting for public support and recognition they say they have so far lacked.

“We feel totally alone,” Farrell said. “Do people even care? Do people even understand what we do for every neighborhood — not just in New York, but in every neighborhood in America?”

In New York City, roughly 40 preschools and daycares contracted with the education department are currently open to serve the children of front line workers. The rest were ordered to close on April 6. Schools that participate in public programs like universal pre-K have continued to receive their full payments, but independent centers like Farrell’s say they are in dire financial straits.

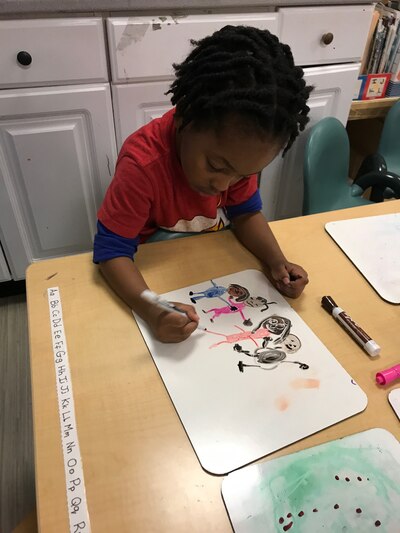

Farrell opened his first preschool about seven years ago in Bed-Stuy, where he grew up and is raising his own family now. Many parents felt like they had to leave the neighborhood to find a quality program, Farrell said, so he decided to create one himself — hand-picking teachers, building a curriculum that celebrates the culture of the surrounding historically black neighborhood, and offering extended hours to better serve the area’s working families.

After the coronavirus shuttered the centers, Farrell’s teachers tossed their “no screen time” rule and switched quickly to virtual learning, offering art classes and Spanish. Still, with parents now at home with their children, and many losing their jobs, enrollment plummeted from about 100 students to 40. Their staff of about 15 fell to just eight teachers.

Running a preschool or daycare is rarely a money-maker, even without a pandemic to contend with. Summers, especially, can be difficult to staff as families often sign up for care at the last minute. This summer will be the hardest yet, with in-person programs seemingly out of the question as the health crisis drags on.

Honeybirds Playschool, serving over a dozen children in a Bedford-Stuyvesant home, was already staring down a budget gap this year. Construction on the backyard play area set the program back $7,000. Then came the order to shut down.

“I really question how we’re going to pay our teachers, and how we’re going to be able to prepare for reopening — if and when that comes,” said Juliana Pinto McKeen, director of the school. “I don’t know what’s going to happen, frankly.”

Both Farrell and Pinto McKeen will be able to hold on for a little while longer thanks to the federal Paycheck Protection Program. Intended to help small businesses continue to pay their employees, both received a chunk of the $660 billion stimulus.

Though the loans can be forgivable, a national survey found that many child care providers are worried that taking the money could be risky when it comes to navigating the fine print and parsing out the rules attached.

Most independent operators are responsible for both instruction and running their businesses — everything from changing diapers to balancing the business ledger. They often lack the kind of back-office support that would help them make sense of a byzantine government program rolled out in a hurry.

Farrell was an accountant before getting into the business of early childhood education, and he still has had trouble understanding the terms of the program. And for all the headache of figuring it out, the financial boost is short-lived, covering about eight weeks.

“What happens to July, August, September, if we’re still not allowed to open?” he asked.

Besides the forgivable loans, the federal stimulus package called the CARES Act earmarked $3.5 billion specifically for the nation’s child care sector — a small fraction of more than $2 trillion in stimulus spending. New York was awarded nearly $164 million, and is using it to subsidize child care costs for low-income frontline workers, as well as to help centers pay for cleaning supplies and protective gear.

Lawmakers are negotiating the next round of federal spending. So far, $7 billion is expected for child care and preschools. That amount would only keep the country’s child care sector afloat for less than a month, said Rebecca Ullrich, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy, and anti-poverty advocacy group.

Public money will be crucial to helping preschools and daycares reopen their doors because families are already tapped dry, Ullrich said. New York has among the highest childcare costs in the nation: Sending an infant to daycare can cost more than public college tuition. Now, with the economy shut down, one in three parents of young children in the state say they are skipping or reducing their meals.

“If we leave child care behind as a system now, we will be paying for it, in terms of our recovery, for years ahead,” Ullrich said. “If child care does not survive the crisis, there will be no going back to work… because people need child care to go to work.”

Compounding the financial pressure, city preschools and daycares feel like they have been left alone to try and figure out what a return to class might look like, without much guidance or communication from the Department of Health, which regulates child care facilities.

Pre-pandemic, the relationship with providers and the health department could often be fraught. Recently, centers faced shortages of critical staff members because of a months-long wait in getting background checks cleared for teachers, therapists, and others. The backlog could make it a nightmare to rehire staff to make up for any layoffs, center directors fear.

Then there are countless other unknowns about welcoming students back to school. Will they need to change pick up and drop off routines? Who needs to wear masks, and when? What happens if someone at a preschool tests positive for the virus?

“We need guidance and support and from our licensing agencies — and from our city and from our country,” said Wendy Jo Cole, director of the Maple Street School in Prospect Lefferts Gardens.

It is almost certain that reopening will not mark a return to normal, which will only add to financial pressures, with centers potentially operating at a fraction of regular capacity.

Cole had to cancel two of the school’s main fundraisers this year, which typically bring in more than $100,000 for scholarships for families, in an effort to make sure enrollment reflects the borough’s rich diversity. She is now thinking creatively about how to shore up her school’s budget, including developing online subscription packages, while anxiously awaiting the day they can reopen.

Even buying cleaning supplies will add to the bottom line — if providers can manage to secure them.

“Getting paper towels and bleach right now is not easy. Preschools are full of sneezes,” Cole said. “I love our school and it saddens me so deeply that we are in this place that we don’t know how, when, and if we can open.”