Happy Juneteenth. Millions of Americans, myself included, are commemorating the symbolic end of slavery 155 years ago on June 19.

I say “symbolic” because slavery technically ended with President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, some two-and-a-half years earlier. But with Southern states in rebellion, enslavement of Black and brown people continued until April 1865, when Gen. Robert E. Lee ended the Civil War by surrendering at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. But word of slavery’s end spread slowly in the South. It took more than two months — until June 19, 1865 — before the last slaves living in Texas learned they were free.

Juneteenth isn’t a federal holiday. But New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo just this week signed an executive order declaring it a paid holiday for state employees, as it is for workers at some private companies.

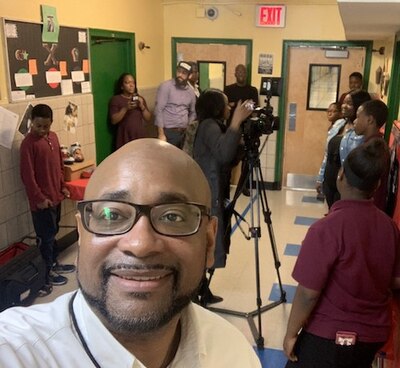

At Meyer Levin Middle School in New York City, where I’m principal, we’re gearing up to celebrate Juneteenth for the fifth year — although this year our celebration will be virtual. The holiday falls about a month after our students take their end-of-grade tests, giving us the perfect window before summer break to focus on Black history — before, during and after slavery.

In years past, we’ve linked the Juneteenth celebration to our Yellowbrick sneaker-design course. This new curriculum helps students design, mold, and market their own pair of kicks, transforming them from consumers to entrepreneurs. Their sneaker design work begins on the heels of our school-wide Juneteenth-related studies. Each student is given a plain pair of sneakers and takes elements of Black history, interprets and internalizes it, and then designs a shoe that represents what they’ve learned.

Last year, one pair symbolized the lost wealth of African Americans over the course of American history. The shoe’s color, bright red, depicted the blood of slaves who put in a century of labor with no benefit or profit. Another pair placed blue Mardi Gras beads on their sneakers to represent Hurricane Katrina’s flood waters, which devastated neighborhoods long home to Black New Orleans residents.

Americans have been obsessed with sneakers for decades. Michael Jordan’s famous “It’s Gotta Be the Shoes” campaign for Air Jordans in 1989 was a pivotal moment in this cultural phenomenon. But in the Black community, particularly in New York City, sneakers are more than a fad. They’re an expression of our students’ culture and aspirations, a way for them to communicate who they are and what they hope to become. Fashion is rooted in the music our students listen to and influenced by the celebrities they follow. Sneakers connect students to the people and ideas they admire.

I first learned about the sneaker program through my friend and colleague Dr. Shango Blake, a principal renowned for tapping into hip-hop culture to improve academic, social and emotional outcomes. He believes that by validating something that holds meaning for students, educators increase the likelihood of engaging them in learning. And that cultural connection helps students understand how mastering the subjects in school can set them up for success in life and enable them to pursue their passions.

There’s no shortage of passion during the Juneteenth and sneaker units. During normal times, kids gather in groups — collecting research, sharing interesting discoveries, developing opinions — before collaborating on a sneaker design that brings the lessons to life. When school buildings were open, they met in classrooms, hallways, the cafeteria, chatting excitedly about ... history.

What role do our teachers play in this process? They’re no longer authority figures depositing knowledge, but rather facilitators tasked with assisting highly motivated learners. Incorporating culture into the classroom better connects them to students, they report, which is the very definition of social-emotional learning.

This year, the Juneteenth curriculum has even more cultural relevance because of massive demonstrations for racial justice taking place. Because of their studies, our students are better equipped to understand the historical underpinnings of what’s going on in the streets and to put the demands being made in context. Some classes have incorporated into this year’s Juneteenth research project the effects of a global pandemic — they are researching which communities are impacted by significant job losses and deaths — and reactions to the killings of black Americans, including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

During a recent remote learning session a student said, “Mr. Patterson, it doesn’t seem to matter if it’s slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, a global pandemic, or racial terror such as police killings. We need to fix this!” His prescription: “Our communities need more business owners and entrepreneurs. We need to learn how to love each other. I’m not with the rioters, but sometimes people have to know you are willing to take it there.” His passion, ability to understand community needs, and desire for love was impressive.

This isn’t just schooling, this is education.

Unfortunately, this year’s Juneteenth celebration will be muted because of the coronavirus. It may not involve sneakers, but students still created projects based on African American history and current events. The level of student engagement and quality of research speaks to the students’ passion for what they are learning. It amplifies not only the importance of exposing them to a culturally relevant, student-centered curriculum but exploring what’s underneath the surface. The goal: giving them the academic and social-emotional support they need.

George Patterson is the principal of Meyer Levin School for the Performing Arts, a school for grades six through eight in Brooklyn’s East Flatbush neighborhood.