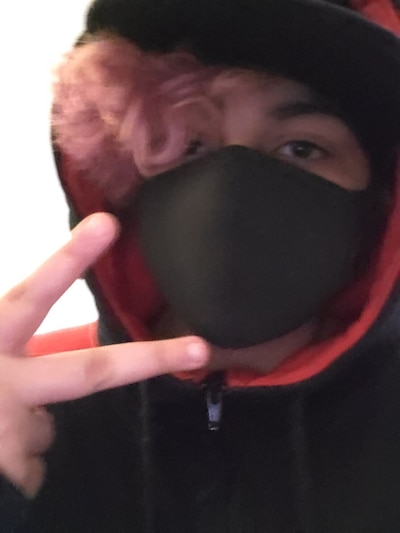

Remote learning has been tough on 16-year-old Tai Muñoz. The freshman at Brooklyn’s Sunset Park High School, who strongly prefers hands-on instruction and is struggling with depression, has been mostly out of contact with school staff.

But after George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis police custody, Tai felt compelled to reach out to a trusted teacher.

“Hello, I know this is very out of the blue, but it needs to be said. If possible, can you please shed light on the recent death of George Floyd?” Tai wrote in an email to Abbey Kornhauser, their advisor and social studies teacher.

Many students and educators across the five boroughs were already dealing with the trauma of illness ravaging their communities and the isolation of being forced out of school buildings due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Now, while apart from their school communities, they’re trying to make sense of Floyd’s death and other recent police killings of black people that have sparked protests and an 8 p.m. curfew in New York City through June 7. New York City’s protests have largely been peaceful but have also resulted in some violent clashes between police and protestors, hundreds of arrests, and incidents of looting.

Students and educators alike are struggling with how to reckon with what’s happening and have important, but difficult conversations about race and violence.

Not only is it a challenge to have these conversations remotely, but it’s difficult to process what’s happening on the city streets as some students, as well as educators, are unable to participate in the protests because of fears of possible health risks. Others who are protesting remain isolated from support systems at their schools.

Here are stories from educators and students about how they’re trying to meet this moment.

‘Don’t give us just a worksheet’

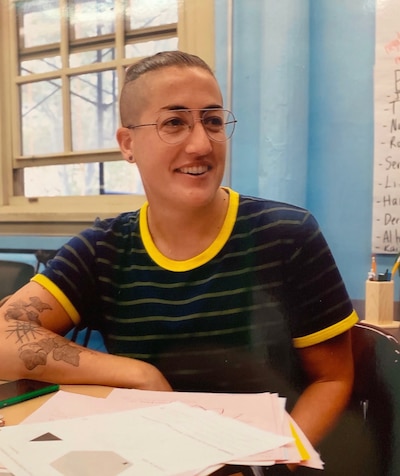

Kornhauser was still processing the recent news and unrest when she received the request from Tai, which came as a surprise after a prolonged silence from the student. She had planned to create lessons about the recent unrest but Tai’s email sped things up, she said.

It was “kind of overwhelming” to find a way in, “especially as a white educator. You don’t want to be someone posting traumatizing videos of black and brown people being killed, so it’s a fine line,” she said.

Since last Thursday, Kornhauser has asked students in her advisory period to talk about what they’ve seen, what they’ve heard, and what questions they have. Some students said they’ve seen many images of looting, while others have talked about concerns about police harassing protesters.

“What I want to do is [provide] the definition of what is looting, what is a riot [and] poke some holes in some of our mainstream understandings of protest,” Kornhauser said.

“I want to offer a counter-narrative to a lot of the images of the demonization of protestors, particularly black and brown protestors.”

Tai, who is Puerto Rican and uses they/their pronouns, said they are passionate about civil rights issues and the Black Lives Matter movement. Some of Tai’s awareness comes from stories their father told of growing up in New York City and being searched by police officers on the street. They wanted to attend protests, but their parents believe it’s too dangerous for safety and public health reasons amid the coronavirus. That’s why Tai turned to Kornhauser.

“I want people to see what is happening,” Tai said in an interview. “I want people to understand it. I want to be very much in the loop of what’s happening, and I feel like if a lot of young people start talking about it, then our new generation can help more than all the people before us.”

Kornhauser wants to share a list of resources her colleagues created giving students an overview of what’s happening and describes “actions they can take from home,” such as how to support student advocacy groups or advocacy campaigns, but is waiting for approval from her school administration.

Tai is craving even more, including more details about topics they believe teachers would think are too sensitive, such as unwarranted police violence toward protestors.

“I want to see actual talks, not just prompts or ‘How do you feel about this?’ Don’t give us just a worksheet,” Tai said. “I want to see everyone’s ideas, what they think of this. I just want to build a community since [for] a lot of us, our parents don’t let us out, but we can be an online presence.”

Activism as artistic expression

In the aftermath of Floyd’s killing, La’Toya Beecham’s South Bronx high school didn’t miss a beat. Officials at Health, Education, and Research Occupations High School immediately sent an email encouraging students to reach out if they needed to talk, encouraged smaller advisory groups to have discussions, and held a virtual town hall that was open to families.

“It was just everybody debriefing as a school,” the 16-year-old said about the town hall. “It was nice to have that place to talk; no one was really judging you.”

Some students asked about how to safely participate in protests or whether it is responsible to participate if a student’s parents are undocumented. Beecham shared a spoken word piece that touched on themes of police violence, race, and colonialism.

She noted some school staffers have encouraged artistic expression as a form of activism, especially among students who are undocumented or have relatives who are and might face more serious consequences of being tangled up with law enforcement. Beecham has not felt safe going to the protests given the police response, though she hopes to attend one later this month with her uncle and brother.

Beecham said schools should use this moment to place a greater emphasis on the history of oppression of black people, ranging from Jim Crow laws to Colin Kaepernick. And she is taking her own advice: When a school counselor recently asked if she wanted to read and discuss The New Jim Crow, a book about mass incarceration, Beecham jumped at the chance.

“I feel like if you’re educated there’s nothing that can stop you because there’s nothing more threatening than an educated black person,” she said.

Calls for more counselors instead of school safety agents

As Elisha Martin watched the video of a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck, the 15-year-old immediately began thinking about how anyone who looks like him is constantly under threat of police violence.

“It feels like I could die at any time for just walking in the street or looking suspicious because I’m young and I’m black,” said the sophomore at Transit Tech Career and Technical Education High School in Brooklyn where teachers and counselors have been offering to talk to students about everything that’s happening.

Under normal circumstances, Martin might have joined protests in New York City as he did last year to call for the firing of the New York police officer who choked Eric Garner to death. But fears over the coronavirus have left him more comfortable participating in activism on social media.

Martin said he sees parallels between the concerns of protestors, who have called out racist policing in communities of color, with the way his own school is policed. In New York City, school security is operated by the police department, and school safety agents have the power to make arrests or issue summonses. Martin must pass through a metal detector every day when he arrives at school.

“We’ve been talking about putting a stop to putting more police presence in schools,” said Martin. “I have like 10 police officers in my school, and it’s a lot. And we don’t have as many guidance counselors, or as many therapists.”

Watching students find their voices

Teachers at Forsyth Satellite Academy, a transfer school serving overage and under credited students on the Lower East Side, have Instagram accounts for their advisory periods where they post questions or discussion prompts as another way to reach students during remote learning.

In the last week, as those accounts focused on recent protests, Floyd, and the Black Lives Matter movement, math teacher Kaitlin Ruggiero received a response from one student that was different from the others: “I think all lives matter,” the student wrote.

If they were in school together, that student’s classmates would probably have chimed in before Ruggiero, she said, to explain the “Black Lives Matter” movement. But confined to their homes, Ruggiero did what the student felt most comfortable with — she texted with him.

“It was a very tense 26 hours waiting for a response from him,” Ruggiero said. “He responded and said, ‘I understand your point. I think we don’t agree about this right now.’ So I offered to be there if he wanted to talk about it more with me.”

That interaction underscores how difficult it can be to have conversations about race and police violence when students and teachers are not in the same room. In this case, Ruggiero said the student hasn’t lost interest — he is still viewing the Instagram account every day.

Another challenge for Ruggiero has been offering advice to students who are out protesting in the middle of a pandemic, most often to those who don’t feel comfortable talking to their parents. This weekend she received pictures from two students who attended protests. One described running home after things got “really scary.”

“They’re returning to spaces where I don’t think they always have a full chance to work through what their experience was,” Ruggiero said.

She tells students to be aware of their surroundings, leave when they feel unsafe, and to wear a mask.

“It’s kind of beautiful to watch some of these students find their voice and use their voice and that sort of thing, but it’s also scary because we’re in the middle of a pandemic,” she said. “So it’s like, ‘OK, I’m so proud of you. Please wear a mask.’”