Crouched over laptops and sitting in lawn chairs, teachers at a handful of New York City schools on Monday refused to enter their classrooms and instead worked on their back-to-school plans outside in a show of protest. Others picketed in the morning, waving signs at honking cars and chanting, “Not until it’s safe!”

The demonstrations showed the serious stress Mayor Bill de Blasio’s reopening plans face with just one week left before students are scheduled to return. New York City stands alone among the country’s largest school systems in attempting to launch in-person learning in September, and it is arguably the most consequential decision of de Blasio’s political career.

The mayor pledged Monday to activate a “situation room” to respond swiftly to positive coronavirus cases in schools. He also promised to have an additional 2,000 teachers available to meet the demand of teaching students both in-person and online. Still, educators wondered why the rapid response team wasn’t ready when they returned last week, and the union representing principals said that 10,000 teachers are needed to fill staffing gaps.

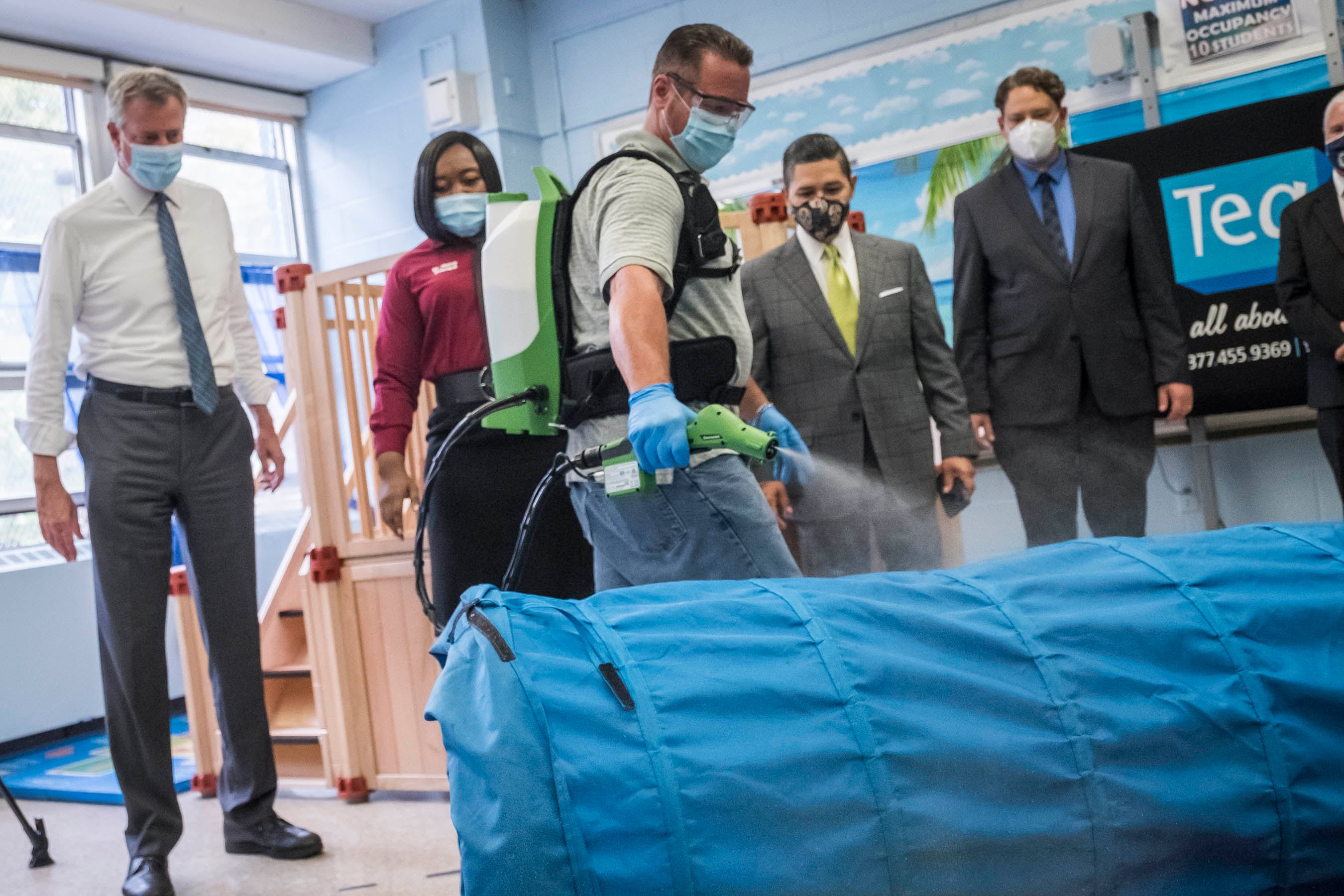

The city is forging ahead with plans to bring students back into buildings on Sept. 21 with a hybrid schedule, where most students attend classes up to three days a week and learn online the rest of the time. Already, the restart of in-person learning was delayed by about two weeks after mounting pressure from educators who said they needed more time. The mayor, who has framed reopening as a social justice issue for public school students and their families, said the city is taking steps to assuage educators’ fears.

With an infection rate hovering around 1%, public health experts say the city is in an excellent position to bring back students — especially as reams of evidence, and many families’ own experiences in the spring, suggest that remote-only schooling could pose a major setback for many of the city’s most vulnerable children.

“We’re completely reinventing the wheel on what public education looks like while we continue to navigate this pandemic,” education department spokesperson Miranda Barbot said in a statement. “These unprecedented circumstances are exactly why we pushed back the first day for students — to give staff more time to work together and plan for the year ahead. We continue to work closely with our labor partners to address any concerns they have.”

Yet confidence seems to be eroding not only among educators, but families as well. On Monday, the number of children choosing to do all-remote school ticked up to 42% citywide. School leaders, meanwhile, have only grown more alarmed over a massive staffing shortage.

Educators reported back to buildings for the first time last week, and some found filthy classrooms, broken sinks, locked-shut windows, and rumors of positive coronavirus cases among staff going uninvestigated by the city’s contact tracers.

When Monday came around, teachers at P.S. 139 in Brooklyn ran extension cords outside and went to work in socially distanced groups that fanned across the school’s front yard and playgrounds. Administrators made snacks and water available, and the school’s tech support worker made rounds, making sure everyone could connect to the Wi-Fi.

“We have staff members who lost family members. We have staff members who lost neighbors. This is serious,” said Megan Jonynas, a music teacher and the union chapter leader at P.S. 139.

“We realized we could not in good faith — for our communities, for ourselves, for our children — return to the building unless our basic needs were taken care of,” said Jonynas.

Her colleagues became concerned throughout last week when it became clear that promised deep-cleanings were not happening, with garbage left in classrooms overnight. Then news spread that a staffer had tested positive for the virus on Friday, but the school community was not officially informed until Sunday.

With the new “COVID Response Situation Room,” de Blasio promised a “rapid response” to positive cases that crop up in schools. The idea is to put multiple arms of the bureaucracy in the same physical room, including the health and education departments along with contact tracers — though it’s unclear to what extent that will speed the process.

“Some people will test positive, and those folks will immediately get support,” de Blasio told reporters. “They’ll be helped to get home, to safely separate. The contact tracing will go into effect right away.”

De Blasio also pointed to the data: 55 staff members in schools as of Monday registered positive tests, or just 0.32% of nearly 17,000 tests — substantially below the city’s average rate of infection.

The mayor’s message, however, was overshadowed by panic the previous week, when reports of positive cases at schools were tallied on social media, days before the education department eventually released its own statistics. At the time, the mayor insisted that more information about infections would be provided “once school begins” — seemingly brushing aside the fact that thousands of educators had already started reporting to school buildings.

De Blasio’s promise of swift contract tracing appeared to be strained even with a relatively low number of cases. At Brooklyn’s M.S. 88, which registered a single confirmed coronavirus case last week, some educators began to hear from contact tracers inquiring about possible exposure to their infected colleague days after the city sent them a letter saying the investigation had concluded and the building was safe for teachers to return. (Barbot, the education department spokesperson, indicated that tracers were made aware of additional close contacts of the teacher who tested positive after its initial round of interviews — something that is “not uncommon,” she said.)

The initially slow response might be difficult to overcome. Top union officials representing teachers and principals raised concerns about delays in confirming positive cases and quickly investigating them to determine which staff members needed to quarantine at home. United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew said it was reminiscent of the spring, when schools stayed open even amid reports of staff members testing positive for the virus.

“Serious issues are still arising from when we get a reported case to when they confirm it. A two- to three-day lag of confirmation of a case is just unacceptable,” Mulgrew said Monday during a virtual press conference. “We’re not going to go back to March.”

At Urban Assembly Maker Academy, teachers marched outside the Lower Manhattan campus before the work day officially started. Joined by their principal and some parents, they unfurled a banner with a list of safety demands and planned another demonstration on their lunch break.

Ventilation inspections released by the city show that the campus, which houses four schools, has about half its supply and exhaust fans working. Those are some of the main components of an effective ventilation system, with supply fans bringing fresh air inside the building, and exhaust fans sucking stale air out. Principal Luke Bauer said that only two bathrooms within the six-story campus have been deemed safe to use.

He and his staff want an update on repairs made to the campus since the city’s last inspection, Bauer said. They also want to see airflow calculations that show how much air is actually coming in and out of classrooms — something the education department has not released. Meanwhile, Bauer said the education department rejected a proposal from the school to phase in students for in-person learning to make sure all of the safety protocols are working.

Roughly 90% of Maker Academy families have chosen remote-only classes for the fall, said the principal, who spent the summer communicating with families about their safety concerns.

“It’s unfortunate that it takes events like parents and teachers picketing to draw attention to something that we’ve been talking about for the last few weeks,” he said. “We all want to be in school. And there’s a way to do that safely. But I’m worried that this way is not safe.”

Health precautions are top of mind for educators, but there are also gaping staffing holes that will need to be filled if buildings are to reopen.

City leaders and the teachers union struck an agreement that teachers should not be responsible for both in-person and remote classes — and has since railed on the city for not filling needed positions, even while facing a gaping budget hole caused by the virus’ economic fallout. Over the weekend, the UFT emailed its members that chapter leaders would be filing reports in cases where teachers were being given assignments that flout the agreement, saying “staffing and scheduling are becoming a nightmare.”

“This staffing dilemma is not yours to solve,” the email assured members.

The mayor has offered only 2,000 credentialed educators, pulled from all corners of the system, to fill shortages. Meanwhile, the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, which represents principals, said that schools will need 10,000 staffers for in-person and remote classes. The CSA derided the city’s staffing agreement with the teacher’s union as “irresponsible” and said that superintendents are telling principals they simply will not be able to fill the need.

“There is now a week to go before students return to schools, and the City and DOE clearly have no comprehensive plan to fully staff our schools,” CSA President Mark Cannizzaro said in a statement.

Meanwhile, de Blasio has not backed down. Facing reporters at a press conference on Monday, the mayor was asked how certain he is that New York City schools will reopen for in-person learning on Sept. 21. His answer was blunt.

“Of course it will open,” de Blasio said.