New York City students will begin to return to their school buildings on Monday, and they face a mountain of worries and unanswered questions.

Next week marks the first time that schools will reopen since the city became the epicenter of the coronavirus this spring, forcing its 1 million public school students to learn online. The city is attempting to become the only school district out of the top 12 largest in the country to re-open for in person learning. But education department leaders, principals, teachers, and parents are still scrambling to figure out what schooling during a pandemic will look like.

The unknowns are dizzying: Will the airflow in schools be working well enough to curb the spread of the coronavirus? Will school buses roll on time for students who need transportation, many of whom have special needs? How will students be disciplined for acting out over Zoom? How much live interaction will students have with their teachers on the days they’re learning online?

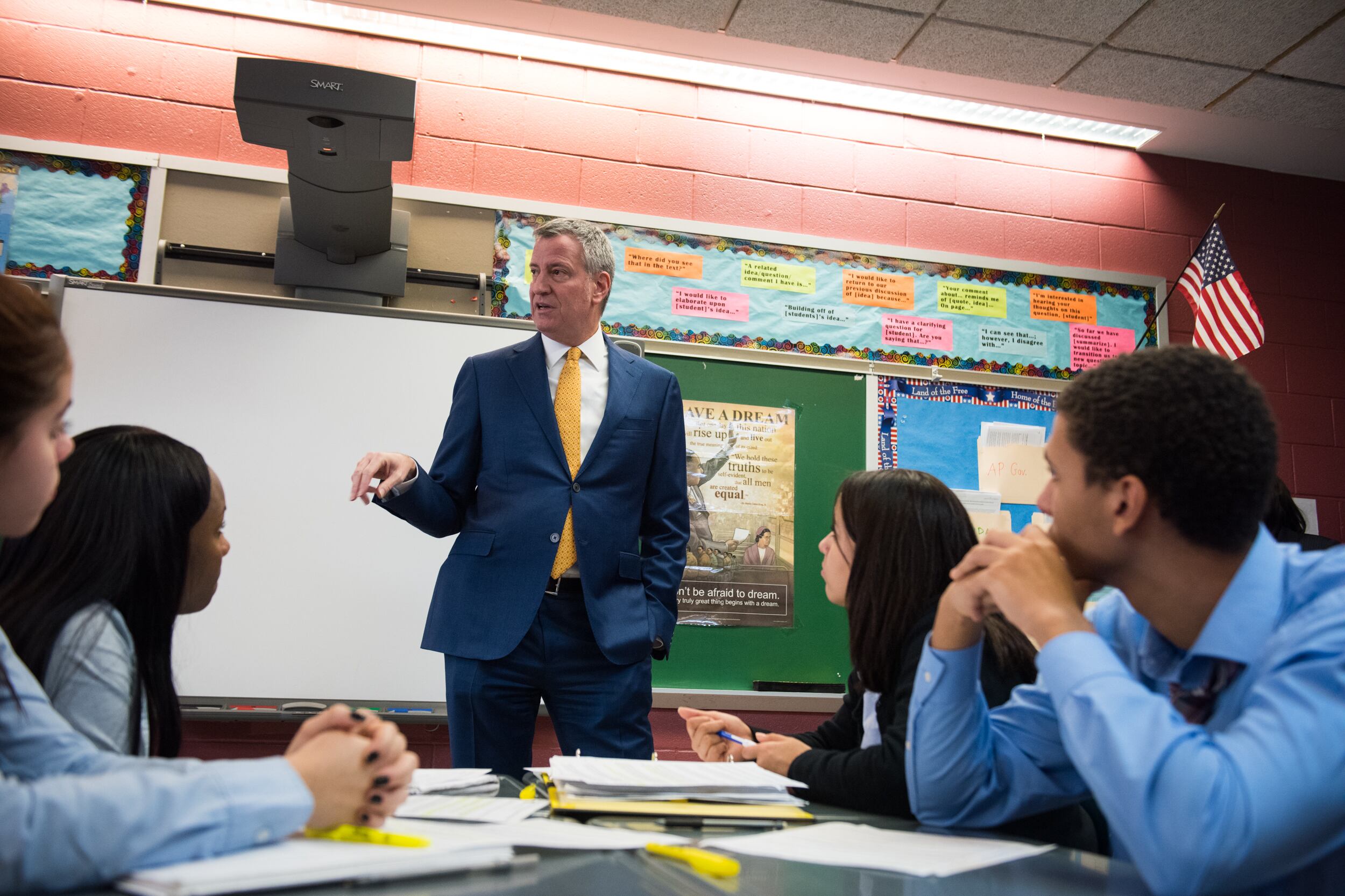

While coronavirus cases soared in the spring, New York City now has rates hovering around 1% over several weeks. Because of that, many public health experts support reopening schools. Mayor Bill de Blasio pledged to shut down the nation’s largest school system again, though, if more than 3% of coronavirus tests come back positive over a seven-day period.

Students are expected to attend classes between one and three times a week, and learn online the rest of the time. City officials already delayed the start of school to give teachers and principals more time to plan for a year filled with new social distancing rules and staffing conundrums. In that time, fresh worries have sprung up as coronavirus cases were uncovered among staff who returned to buildings last week. Already, some teachers are refusing to enter their school buildings, working outside instead to demonstrate their distrust for the city’s back-to-school plans.

“We’re going to keep making improvements as we go along, we’re going to keep adjusting and figuring out what we need in terms of staffing,” de Blasio told reporters on Wednesday. “We’ve come this far. We’re going to keep doing what we have to do to make it better every single day.”

Here’s what we know — and what we don’t — about the start of the school year.

Has the city invested enough in improving remote teaching?

Much of the focus on reopening schools has centered on health and safety issues, which are crucial for in-person learning. But the majority of instruction this school year will be conducted virtually, since most students will only be allowed to attend school one to three days a week, and 42% of students — and counting — have opted for fully virtual learning.

While much of the reopening logistics focused on personal protective equipment, cleaning supplies, and ventilation, comparatively little energy has been spent adapting curriculum to suit the remote learning environment. And without the education department providing a wide array of materials and templates for strong remote teaching, schools are largely coming up with their own strategies. That will likely produce uneven results, experts say.

“The operational only accounts for at most half of the problem, and we have to talk about instructional quality as well,” said Tom Liam Lynch, who runs the website InsideSchools and has previously consulted with the education department on instructional technology. “There isn’t a lot of direction or leadership when it comes to this part of the conversation.”

Education department officials have said parents should expect to find a better virtual learning experience than when the system abruptly shut down in March. The city has held training sessions for teachers on a range of topics, including how to adapt core academic subjects like reading math and how to set up virtual science classrooms. And teachers now have a few months of remote teaching under their belts.

But some teachers said they were less excited in the training sessions the department was offering — if they’d heard about them at all — and were more interested in opportunities to learn best practices from each other.

“I wish there wasn’t so much reinventing of the wheel,” said Lynn Shon, a science teacher at Brooklyn’s M.S. 88. “We’re all busting our tails making different versions of the same thing.”

Will schools have enough teachers?

Staffing remains one of the biggest challenges for school leaders. In-person classes will be smaller because of social distancing requirements, and students learning remotely from home also need instruction. Meanwhile, educators have gotten medical accommodations to work from home or requested family leave to take care of children or high-risk relatives.

The union representing principals and other administrators said schools are short 10,000 teachers. The mayor said this week the city plans to shift 2,000 education department employees into school teaching positions to address the staffing shortage, and the education department said it’s searching for other ways to fill gaps. During a town hall with District 15 parents Wednesday night, Carranza said the city is working with the City University of New York to place adjunct professors and graduate students at schools. The city also backpedaled on its promise to offer live instruction to the hybrid students on their remote days — a shift that reduces some of the staffing pressure.

The math still doesn’t add up, and it remains to be seen how the flux of students from in-person to full remote, which students can opt into at any time, will affect the impossible puzzle of creating class schedules — another conundrum Carranza has acknowledged.

Students continued to opt into remote-only learning even as online teacher check-ins kicked off Wednesday, educators said.

On top of the staffing shortage, will we see teacher layoffs?

New Yorkers are bracing for a wave of layoffs to hit the public sector. As the city faces a $9 billion budget hole over two years, de Blasio was expected to send layoff notices this month to about 22,000 public workers across all city agencies. He backed off at the last minute at the urging of union leaders, the Wall Street Journal reported.

Those layoffs might still happen if state lawmakers don’t give the city permission to borrow $5 billion or if the city doesn’t get help from the federal government. City officials have refused to specify how many at the education department could lose their jobs.

Separately, the city is also facing a budget squeeze from the state, which is temporarily withholding 20% of regular payments to districts across New York but announced Wednesday that it won’t withhold any money at the end of this month. If Gov. Andrew Cuomo decides to make these temporary cuts permanent, that could result in $2.3 billion of cuts for city schools, and the city could see 9,000 teachers laid off, according to Chancellor Richard Carranza. Such a loss would force the school system to revert to full remote learning, Carranza has said.

City Hall did not respond to Chalkbeat’s questions about potential layoffs or when the mayor will make a final decision. Freeman Klopott, a spokesman for the state’s budget office, declined to say when exactly Cuomo will decide on whether to make the 20% funding cuts permanent.

How will students be graded?

This was a major flashpoint in the spring, when school buildings first shut down because of the coronavirus.

Many argued that the abrupt shift to remote learning left behind students lacking stable home environments, reliable internet connections, or laptops. The struggle to keep up was only exacerbated by the health crisis, which fell disproportionately on Black and Latino communities, and poor neighborhoods. For those reasons and others, parents, and advocates pushed to suspend traditional grading.

Others, however, argued that children who managed to do well under tough circumstances should be recognized with high marks. This was especially true for parents eyeing competitive middle and high school placements for their children, since grades are a major factor in winning admission.

In the end, the city moved to a system more like pass or fail.

The education department has not yet said whether that policy will stick this year, or if schools will be allowed to design their own grading scales.

How will middle and high school admissions work?

More schools in New York City use “screens,” or competitive admissions standards, than anywhere else in the country. The competitive admissions process helps drive New York City’s status as one of the most segregated school systems in the country, and many parents, educators, and students have been advocating to end or pare back screening well before the coronavirus hit.

Competitive schools often use grades, in addition to state test scores and attendance records, to make admissions decisions. But the city nixed traditional grades at the end of last year, state tests were canceled, and schools could not consider attendance records for admission decisions.

Without those most commonly used screens this year, it remains unclear how students will be selected for sixth and ninth grade.

Some parents have insisted that schools be allowed to look at students’ academic records from before buildings were shuttered because of the pandemic, or even from the year prior — when students were only in third and sixth grades. Others have argued that would be unfair, and the education department has released data that shows those measures are often not reflective of students’ performance later in their school careers.

The city promised to announce a decision by this summer on how admissions would work for rising middle and high schoolers. But parents, students, and schools are still waiting. The department, which has held multiple virtual meetings on the topic, has gathered “important ideas and feedback” and is still working to create a “fair and equitable” plan, a spokesperson said Wednesday.

Meanwhile, the application process typically kicks off as soon as classes begin, with open house tours, and sign-ups for interviews and tests.

When will families find out if they score free child care seats?

Because of space constraints and social distancing mandates, children who attend school in person will only be in classrooms for 5.5 hours, one to three days a week. Parents trying to head back to work — or just get more work done from home — will face the same child care challenges as when schools first shut down.

De Blasio promised free child care for 100,000 students on the days they are not learning in school buildings, much like the city did throughout the course of pandemic for the children of essential workers. However, only 30,000 spots will open by the first day of in-person classes. And parents have yet to learn whether they’ve snagged a seat.

“We are finalizing assignments and will have more information to share with families over the next few days,” a city spokesperson said Wednesday.

Charter school students are not eligible to enroll, the New York Times reported, which leaves out about 13% of the city’s public school enrollment.

Those who do land a spot could still have a child care crunch: Getting to and from the centers may be difficult, as officials have not said whether transportation will be provided. And after-care will be offered on a site-by-site basis, but is not guaranteed.

Will all children have a device when school starts?

Families can request devices online here, which will be routed to their schools, or call 311, schools officials said.

When remote learning started in the spring, schools gave students devices from their own stockpiles. Additionally, over several months, the education department purchased and distributed more than 320,000 internet-connected iPads to students who lacked reliable internet access or technology. Some 30,000 iPads remained in the department’s coffers at the end of July, but officials did not say how many are left now. All of these devices can also now operate as hotspots, officials said, which can provide internet connection for up to five other devices.

The responsibility of purchasing laptops and tablets will fall once again to principals this year, as will the job of redistributing the DOE-issued iPads from the spring. School leaders and their union are concerned about having to buy new devices as they’re dealing with smaller budgets this year. They’re worried about meeting the demand — while many of their returning students may be set with devices from the spring, school leaders must account for newly enrolled students or students who no longer want to share one device between multiple siblings.

“I know that our schools, as they’re preparing for the start of the school year, have reached out to families and students to make sure that they do have a device, they do have connectivity,” Carranza told reporters Wednesday. “And if they don’t, then we’re in communication with them to provide them those, either devices or connectivity.”