For the first six years of my life, I grew up on the island of Trinidad.

I spoke with an accent, pronouncing three as “tree.” I ate Caribbean food, such as roti, aloo pies, and pelau. I was accustomed to drinking water straight out of a coconut, eating mangoes from my grandfather’s mango tree, encountering snakes and lizards, and seeing houses in every color of the rainbow.

Then I immigrated to the United States with my mother, and we haven’t been able to visit Trinidad since. I enrolled in elementary school, where students made fun of my “trees” and teachers corrected them.

School lunches here tasted like they were made to feed as many mouths as possible rather than to be enjoyed. They mostly consisted of fast food with a side of canned fruit poured into a plastic cup and milk as our only option for hydration. And here, people dried their clothes in a dryer, not outside on a line. There were no vines with berries to pick, no roaming animals — just cars, crowds, and busyness. It was hard to feel at home among the drab concrete buildings.

I soon made friends with the kids from Caribbean countries. We reminisced about authentic Caribbean food, laughed at each other’s impressions of Caribbean dialects, and listened to calypso. Being with them and doing these things made me feel closer to home. Eventually, though, I got used to the way those around me spoke and mimicked it with the aid of American TV shows like “Good Luck Charlie” and musicians like Mariah Carey. I learned to pronounce my H’s and soon spoke with what I took to be an American accent.

Some adjustments were harder. There was one girl who compared my skin tone to mud. Another girl, who despite being Black herself, often told me “how much lighter” her skin was than mine, which “made her more beautiful.” I also had white friends who told me how pretty I would look with straight hair.

American beauty standards made me self-conscious about how I looked for the first time. In Trinidad, most people living there are either Black or South Asian, and I did not experience racism around skin color. Now, I found myself wanting to be lighter.

At the same time, I noticed that I didn’t feel any connection to my African American classmates or my African Caribbean classmates who had adapted to African American culture. I wanted to be friends with other Black students at my school, but I couldn’t relate to them. After all, we weren’t interested in the same sports, music, or clothing brands. I didn’t speak African American Vernacular English. I ate different foods at home and didn’t celebrate the same holidays, like Juneteenth.

While examining my disconnect from African American culture, I began to think a lot about my African ancestors, whose own history was disrupted by colonization and the slave trade in the Americas. I became more aware of what I shared with so many African Americans.

I continue to explore more about the connections among African, Caribbean, and Black American cultures, and I plan to teach parts of those cultures to my children one day. For example, I watched videos about cooking soul food and its cultural importance, and I saw traces of it in Caribbean dishes, such as macaroni pie. I watched American Black family sitcoms like “Black-ish” and read books that centered Black families, such as “Piecing Me Together” by Renee Watson. Like those in the Caribbean, many African Americans are religious and churchgoing, as is my family. All around me, I now see people who share my dark skin and extremely curly hair, which, despite my white friends’ comments, I’ve grown to love.

I’ve started to connect with more classmates and made friends by teaching them Trinidadian versions of American words, like bacchanal instead of chaos or drama. I show them fruits we eat there that aren’t popular in the U.S., like chennet, which is a little bit like an orange. In return, I learn about popular meals here and family traditions around holidays like Juneteenth.

I don’t know what African region or tribe I come from. That is a deep wound for me. I can’t help but wonder what customs and traditions I would have been raised with if my family knew our African ancestral roots. What language would I speak? What traditional clothing would I wear? What dances would I partake in, and what holidays would I celebrate? That’s why I plan to take a DNA test and find out where my African ancestors are from. It is my heritage to claim — connecting me to and differentiating me from others all at once.

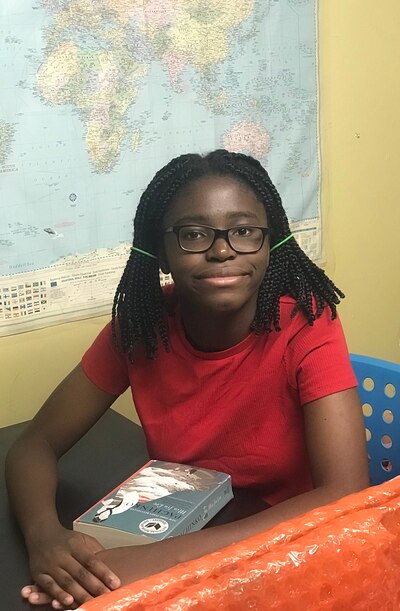

Etana Williams is a 16-year-old from Brooklyn. She is a student at Brooklyn Technical High School, and she enjoys crocheting, reading, and playing the guitar in her free time.

A version of this essay originally appeared in YouthComm magazine.