Meisha Ross Porter, who rose through the education department’s ranks as a teacher, principal, and executive superintendent, will become the first Black woman to lead the nation’s largest school system.

Her appointment comes after the surprise resignation of Chancellor Richard Carranza Friday morning and just 10 months before Mayor Bill de Blasio will leave office.

But even if Porter’s tenure may be brief, as a new mayor is likely to pick a new chancellor, she will not simply be turning out the lights on the remaining months of the mayor’s term. She is inheriting a system that has been rocked by the coronavirus pandemic, and she will immediately face enormous responsibilities: determining how much in-person instruction schools can offer in the coming months, developing a plan to catch up students whose education has been derailed by the pandemic, and gaining buy-in from bitterly fractured communities of families and educators.

“I promise we’ll do everything to reopen schools, starting with high schools, we’re ready to go,” Porter said at a news conference, hinting that she may jumpstart reopening high school campuses, which have been shut down since November, even as elementary and middle schools have reopened. “We’ll expand the learning opportunities and do more to address trauma and academic needs, because we know that that is very real.”

Porter is well respected among many of the city’s education leaders and known for building trust with parent leaders and principals, according to people who have worked with her. She also brings a deep understanding of the school system, a labyrinthine bureaucracy with roughly 150,000 employees and a $34 billion annual budget.

“For the first time in a number of chancellors, principals and superintendents are gonna feel like they have a friend, someone to talk to and someone who understands them,” said Richard Kahan, founder of Urban Assembly, a nonprofit that has created 23 public schools, and hired Porter for her first teaching job. “It hasn’t been that happy a place for principals for a long time.”

Raised in South Jamaica, Queens, Porter graduated from Queens Vocational and Technical High School, where she majored in plumbing.

Porter was about 17 and leading an anti-drug organization for teenagers when Kahan, then overseeing an urban planning effort for the Bronx, approached her to help his team craft policy ideas, he said.

Shortly after, Kahan tasked Porter with helping to plan Urban Assembly’s first school, Bronx School for Law, Government, and Justice. When the school was established, Kahan hired Porter to oversee its outside partnerships, unaware that she was studying to teach. Porter was later brought in to teach at the school, rising several years later to principal.

She was able to build relationships with students quickly and often saw opportunities to connect their learning to real-world issues, according to David Banks, the school’s founding principal.

After a student commented on a cigarette advertisement that faced the school building, Porter pushed to incorporate lessons about the effects of smoking. She also encouraged a letter-writing campaign pressuring then Mayor Rudy Giuliani to sign a bill that would ban advertisements for tobacco near school grounds, Banks said. Giuliani signed it into law, though it hit legal roadblocks.

“Those kids felt like they had something to do with it,” said Banks, who is now president of the Eagle Academy Foundation. “She’s not that traditional stuffy school leader. The kids adored her and they saw her as one of them.”

During a visit to the school when Porter was principal, Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. recalled feeling struck by how she had students settle escalating disputes: They held a trial with student attorneys, a jury, and a judge.

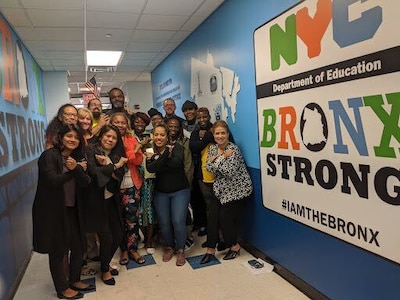

After 18 years at the school, she left her post as principal to become a regional superintendent for Bronx District 11. Three years later, in 2018, Carranza tapped her as one of his newly created executive superintendents, overseeing all Bronx schools. Porter drew some criticism in 2019, when the schools watchdog received a complaint that she had enlisted subordinates to fundraise and organize a party to celebrate her promotion. The office later dropped its investigation.

Porter’s sense of what to prioritize when the pandemic hit exemplified her leadership style, according to principals and nonprofit leaders.

Luis Torres, principal of P.S. 55, said Porter helped bring to life his idea to create educational programming for children on public access television station BronxNet by rallying support among schools in the borough, so that teachers and administrators could create pre-recorded lessons for the program. And when some students across the Bronx were still deviceless in January, Porter pushed elected leaders for help, said Torres, who said he has known and worked with Porter for 15 years. Torres said it helped fill the gap at his own school.

“Whatever it takes to get things done, this is what Meisha will do and I’ve seen it with my own eyes,” Torres said. “That’s why people appreciate her, because even though she was the executive superintendent, she gets her hands dirty, and she’s never forgotten where she came from.”

In another instance, Porter tapped New Visions for Public Schools, a nonprofit group that manages a network of district and charter schools, to help build out its data tools so that principals could better track whether students were failing to submit assignments in Google Classrooms or even whether they lacked devices for remote learning.

“She requested that we provide support and worked with us to make sure those supports complemented the greater work she was trying to do,” said Mark Dunetz, the president of New Visions. “She is somebody who is just very clear and effective.”

Bronx parents have praised Porter as an ally. The New Settlement Parent Action Committee, or PAC, an advocacy group based in the South Bronx, got word in 2018 that the education department was setting up new teams to focus on equity issues in District 9. The team’s goals targeted many of the same issues the committee had been focusing on for years: pushing for culturally relevant curriculum that reflects the borough’s diversity, discipline reform, and more.

PAC wanted to join the equity teams, to bring the perspectives and support of parents to the mix. But they ran into roadblocks and excuses about why they couldn’t. Until they reached out to Porter, who had recently been appointed executive superintendent.

“Meisha Ross Porter went to bat for us. She told the equity team we must be at the table — that there’s no equity team without us,” said Ronnette Summers, a parent advocate in District 9 for more than two decades. “She was just really, really receptive. Surprisingly receptive.”

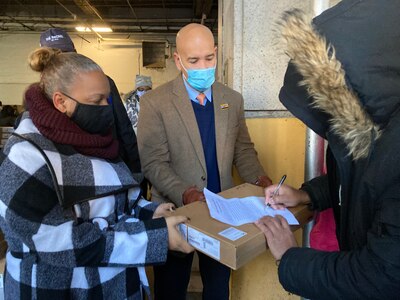

Throughout the pandemic, parents and school officials on the equity teams have worked together to make sure students have internet connections and devices, with parents passing along the names and contact information of hard-to-reach families whenever officials ran into dead ends or struggled to learn the extent of the need. Porter is a fixture at meetings and other events like town halls — a constant presence that Summers called “unheard of” in all her tenure as a parent advocate.

Aide Zainos, another member of PAC, said she is particularly appreciative of Porter’s help ensuring parents have school materials and meetings translated in their native language, whether that’s Spanish or African dialects.

“She understands the needs of families in the city,” Zainos said in Spanish, adding that the equity teams have included “all cultures and languages.”

But Porter may not have a lot of runway to execute her own vision, especially as Mayor de Blasio’s propensity to micromanage his agency chiefs is well known. One factor in Carranza’s resignation, according to the New York Times, was growing tensions with the mayor about how to handle admissions to the city’s Gifted & Talented program.

At a press conference on Friday morning, Carranza left her with one piece of parting advice: “Do you, be you, lead with the heart that you’ve led in every one of the assignments that you’ve had in New York City.”

Summers credited the outgoing chancellor with helping Bronx parents advance issues important to them, even in the face of “pushback from some of the affluent places that weren’t ready to give up stuff.” Throughout his tenure, Carranza, who is Mexican-American, faced racist rhetoric while pushing for school diversity and anti-bias training for teachers.

Summers predicted that Porter will come up against some of the same challenges, but said the new chancellor won’t stand alone.

“There’s going to be a lot of pushback for her being a woman, and a woman of color. But I think she’s capable of taking that on,” Summers said. “We’re going to have her back.”