Danielle Guggenheim missed her physical classroom so much, she took on a weekend volunteer shift at her neighborhood farmers market in the Bronx.

Every Saturday this past year, weather permitting, Guggenheim has sat outside and read books aloud to any children that wanted to stop and listen while their families shopped. Guggenheim said she is grateful to have the option to work remotely during the COVID-19 crisis, but she misses in-person interactions intensely.

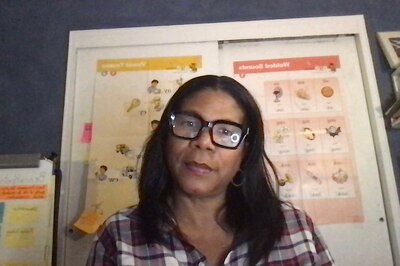

Guggenheim has been an elementary special education teacher at P.S. 200, The James McCune Smith School, in Harlem for six years and an educator in New York City for more than two decades. She describes this pandemic year as “the most difficult in teaching and in mothering” — she shares an at-home workspace with her 12-year-old daughter.

Still, Guggenheim believes the core of her work hasn’t changed despite the difficult switch to remote learning: To care for students and their parents as if they are family. She spoke with Chalkbeat recently about why she encourages her families to take on the role of “parent coaches,” what she does weekly to keep anxiety at bay, and lessons she hopes education leaders will take with them post-pandemic.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity. This is part of an ongoing, collaborative series between Chalkbeat and THE CITY investigating learning differences, special education and other education challenges in city schools.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

My uncle says from the time I was 4 or 5 that I was teaching. Which I guess is not surprising, because I come from a family of educators. My father was a teacher and my mom, a retired principal. I have an aunt who was a professor in the Black Studies program at the City College of New York. I don’t think I decided, I think it was a calling.

What does a typical day look like for you now?

I start every morning with a walk. After months of our country’s pandemic crisis and then George Floyd’s murder — I realized I was experiencing severe anxiety attacks. To alleviate my anxiety, I started to walk around a reservoir in my neighborhood daily, and I immediately realized that it had a calming effect on me. This is how I start every day before logging on for classes and small group check-ins with my students. I’m on the computer all day and then I make calls to parents or help my daughter with her work. It’s difficult — that daily walk is so key to my mental health.

What challenges do you face teaching students with disabilities during this year?

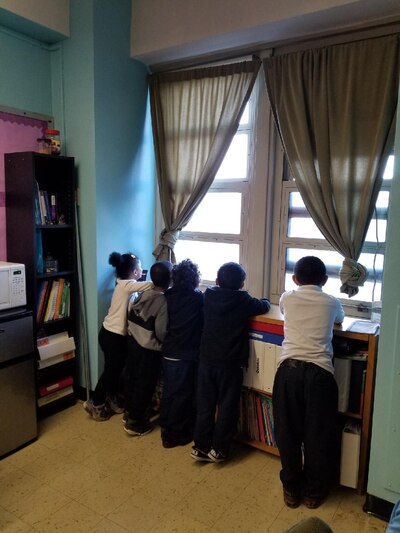

I’m also learning as we go. I’ve been in a physical classroom for 20 years, I’m great at that. With technology, it’s a steep learning curve to be online. I’m not sure I have been able to replicate that hands-on learning experience that’s key to teaching young students with disabilities. I’m also not able to get them to play with one another or interact with each other online in the same way.

I work with students on the autism spectrum, and one of the challenging behaviors I would work on with the parents is limiting the usage of the devices. Now that we are relying on them so heavily, I’m a bit concerned. What will be the long-term impact of so much screen time?

What’s your advice for great parent relationships?

I have to get to know my kids. And knowing them means that I also have to get to know my families, the caregivers. At the start of every year, I make the time to listen to their stories and find out what their goals are for their children. I was taught that my teachers were extended members of my family. I really feel that children learn best when they are in a village of love. I love my kids, and I come to love their parents as well. We’re family, your kid is mine. I take that seriously.

After I listen to my parents and understand their hopes and concerns, I teach them how to work with their children. I model for them a lesson and explain why I am teaching this way. Parents are their child’s first teacher. I find that in the community I work in, the parents don’t always feel empowered. People don’t appreciate the assets that they have. I feel that it is my job as an educator to teach my students to be gifted learners, yes, but also to teach my families how to work with me as parent coaches, as co-teachers in their home classrooms.

How has this work with students and their families changed during the pandemic?

Relationships are everything, and that hasn’t diminished this past year, despite so much change. I’m still accessible, and I work with parents on certain lessons, so they know how to best help their child. For example, if I’m working on a kindergarten lesson, I explain why it’s important for kids to be able to know the letter sounds, isolate the letter sounds, and blend them. That helps them with decoding, literacy, with fluency. Parents become so invested when they understand the science or philosophy behind a lesson, they see it as something they can help with at home rather than just work we do at school. It’s not just a lesson — it’s setting up their child to read and speak.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your school?

I live in the Bronx, in an underserved community that things “happen to.” You look up and a building has been torn down, but your community didn’t know that was happening. You’re not at the table where decisions are made about your community. This brings me to why schools, especially in urban areas, need to put community members at the decision-making table.

And we will tell you that the way we view school needs to change, before this pandemic and after. In taking my daily walks for my mental health, I realized that being outdoors helped my state of mind and that my neighborhood and school lack open green spaces. This year, I started doing read-alouds at the farmers market in my neighborhood because I realized children were gathering there.

I did it more for me than anything else, but I realized how much better it was to sit in the sunshine, feel the grass, and learn without having to sit at a desk for hours. I do hope this pandemic has shown us the potential for more outdoor learning, and if we could prioritize this, I believe students like mine would benefit greatly.

This story is part of a collaboration supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.