A pair of teen scientists from Queens worried that the dangers of climate change had receded from the minds of many of their peers, as COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, and anti-Asian hate crimes have defined the past year.

So Behruz Mahmudov and Kayla Wang, juniors in the Carl Sagan STEM program at Forest Hills High School, wanted to center climate in their scientific work and their activism.

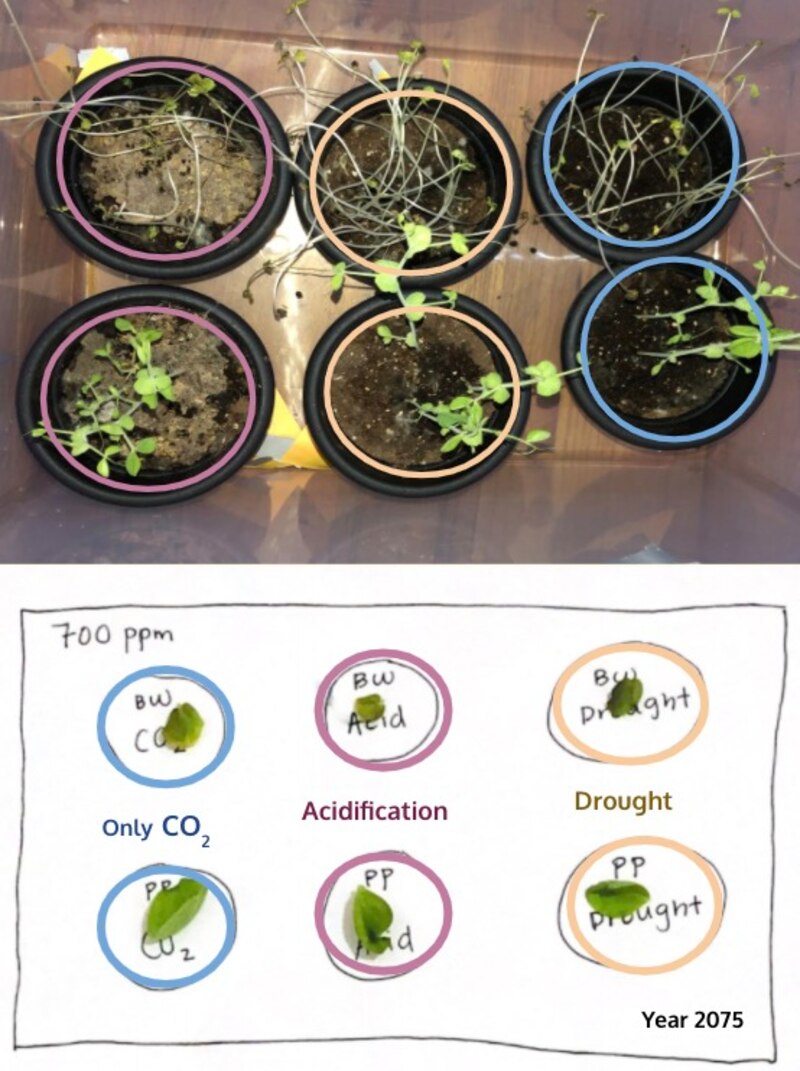

Over the summer, they began examining how future environmental conditions would affect the cell structure of stomata, which are like the lungs of a plant.

Their project, which studied how increased carbon dioxide, drought, and soil acidification affected the size and density of stomata in buckwheat and pea plants, was one of 13 finalists from the Terra New York City STEM Fair. Now they are competing in the prestigious Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair, where 1,800 students from around the world vie for nearly $5 million in awards, scholarships, and prizes. The virtual judging kicks off May 3.

“Climate change has been overshadowed by other news like the elections, Black Lives Matter, Asian American movements, and most obviously, the COVID-19 pandemic, so we thought it would be perfect to bring more attention to climate change as [carbon dioxide] levels are still rising, and time is running out,” said Mahmudov. “All of these things are important, but climate change is going to be irreversible in less than a decade. The time to act is now.”

Wang added: “We also have to recognize the intersectionality of the climate crisis in terms of environmental justice, and how that can connect back to human health.”

Just as people are talking about how COVID-19 is affecting widespread unemployment, climate change has major economic and social consequences, particularly on communities of color, she said.

“If we really think about it, the climate crisis is really affecting Black, brown, and low-income communities the most,” Wang said. “So that’s why we wanted to zoom in on one aspect of it, specifically plant physiology and the biological standpoint because autotrophic species influence our entire ecosystem.” Autotrophs, for the uninitiated, are organisms that can produce their own food using light, water, carbon dioxide, or other chemicals.

Both teens are finding ways to align their activism and interest in science. Since he was young, Mahmudov would try to recreate scientific experiments he found on YouTube, including one where the smell of burning rubber alarmed his parents. (Needless to say, don’t try that one at home.) He’s also a poet and youth activist, who has helped organize rallies related to supporting Asian Americans and the Black Lives Matter movement. Wang, who writes for a Gen Z-focused newsletter called Politically Invisible Asians, is also part of her school’s Green Team, through which she and like-minded classmates advocate for a state bill that would raise $15 billion a year from fossil fuel companies to fund green jobs.

The duo conducted their experiment as part of their Competitive Research elective class. In a year without access to their school’s lab, the students still managed to do a sophisticated experiment about climate change by being smart, scrappy, and taking advantage of their social networks.

Taking COVID-19 precautions, they set up their experiment in Wang’s backyard in Corona, Queens, where her gardening grandfather had long instilled in her a love of growing things. They borrowed microscopes from the school but hit a snag securing a carbon dioxide tank they needed. Finally, they found one through Mahmudov’s uncle, who is in the construction industry and had a connection at an industrial gas company. They also needed a measurement instrument called a porometer, enlisting their class to enter a raffle for one, only to learn the company refused to work with anyone but established scientists. They ended up pivoting by creating a different equation to conduct the measurement. Even without the tool, they could still predict and make valid conclusions.

The buckwheat plants, which tend to survive a lot of harsh environments, died after two weeks of the experiment, the teens were surprised to discover. The pea plants fared better.

“The buckwheat couldn’t adapt that fast,” Mahmudov said, “which went against one of our hypotheses: that all land plants would respond similarly to these conditions.”

They believe the results indicate that because of climate change, “We might lose some plants. They might go extinct,” according to Mahmudov. “Adaptations take years. In the past, plants were able to adapt because change wasn’t that rapid… But with climate change, changes are happening so fast, so one could argue that they can’t adapt as rapidly.”

But they’re hopeful about the clean energy investments proposed as part of the Biden administration’s $2 trillion infrastructure plan.

“That could potentially slow down climate change, giving plants enough time to kind of adapt,” Mahmudov said.