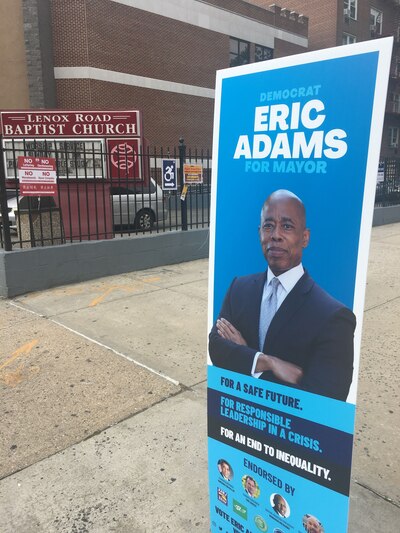

Eric Adams — who might want to keep schools open year round and have a permanent remote learning option — snagged the most first-place votes in the Democratic primary for New York City mayor Tuesday. But the winner remains uncertain since the race won’t be officially called for weeks.

Adams led the pack of Democratic mayoral hopefuls with 31% of the votes based on 85% of the ballots cast in-person on Primary Day and the nine-day stretch of early voting.

The Brooklyn borough president has talked about keeping school buildings open year-round and providing child care and STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) programming during the summer. Adams would also create a long-term remote learning option — though he would not put 400 children with one virtual teacher, as he said at one point, raising eyebrows and ire across the city. He would fund online schooling by levying a data tax on big tech companies that sell private data to advertisers and others.

The winner of the Democratic primary is largely assumed to become the next mayor in this overwhelmingly Democratic city. But the city may not have an official Democratic mayoral primary winner for weeks as tens of thousands of absentee ballots must still be counted, as the pandemic allowed for any voter to request a mail-in ballot. There’s another complicating layer with ranked-choice voting. For the first time, voters were able to rank up to five candidates in order of preference. Only their first-choice candidates are immediately being counted, but their No. 2’s and beyond could be consequential as the ultimate winner might not be the person with the most votes in the top slot. Ranked choice votes are expected to be counted on June 29.

Though the new mayor won’t take office until the middle of the next school year, the timing will still be consequential. After more than a year of disrupted learning and an influx of federal COVID relief funds set to be spent over the next few years, the next mayor — and their schools chancellor — will likely have an outsized influence on schools.

Chalkbeat previously compiled where Adams stands on some of the most pressing school issues, based on interviews and his education platform.

Integration efforts, Specialized High School Admissions Test and gifted and talented programs

New York City has the most racially segregated schools in the nation, and Bill de Blasio’s administration has taken a piecemeal approach to address this.

Adams has said he would add more selective high schools, and has argued that expanding gifted classes to more communities will lead to a more representative group of students being admitted to the city’s competitive schools. He has also said he would create more slots in the specialized high schools for the top performers from every middle school.

When it comes to the Specialized High School Admissions Test, an exam that is the sole admission criteria for eight of the city’s specialized high schools, Adams would not remove it. He said the state must determine the fate of the SHSAT, which is mandated by the Hecht-Calandra law.

Adams also said he would keep the admissions test for 4-year-olds for seats in the city’s gifted and talented, or G&T, programs, serving roughly 16,000 elementary school students.

White and Asian students make up the majority of specialized high school programs as well as G&T, even though the city’s school system is majority Black and Latino.

Police in schools

New York City trails behind some other school districts in rethinking its approach to police in schools, though de Blasio promised to transfer oversight of school safety agents from the NYPD to the education department.

Adams, who was in the NYPD for 22 years, has indicated that he wants safety agents to remain, but there should not be a “police culture” in schools.

Charters

Often a political lightning rod, charter schools serve roughly 140,000 NYC students.

While they have not been a central component of Adams’ education plan, he has indicated on multiple occasions that he supports them. (A pro-charter school advocate started a political action committee to raise money for Adams.)

He has indicated that he favors keeping the cap on charters. At the same time, he has said successful charters should be duplicated while failing ones shut down. He also said he supports unionizing charters.

Plan for English language learners

More than 150,000 NYC students, or 15%, are designated as English Language Learners.

Adams recognizes that NYC is not an English-only city, and he is committed to hiring more bilingual educators and aides, particularly for the roughly 4,000 students who require bilingual special education. Adams would also create a professional development program to ensure teachers are responsive to ELL students.

“Teachers will be trained in how to adapt to the cultural perspectives their students may bring to the classroom, ensuring that students from all backgrounds are given an equal opportunity to succeed,” Adams’ platform states.

Plan for students with disabilities

More than 200,000 students, or 20%, are classified as having disabilities that legally entitle them to receive special services in school. About 25,000 of these students who require more intensive support are in District 75, which exclusively serves students with special needs.

Adams would prioritize real-time tracking to measure which students with disabilities are not receiving all of their services so that those situations could be addressed before the year is over. Adams said he would hire more bilingual special education teachers to address chronic gaps. He would also make dyslexia screenings universal.

Plan for students in temporary housing and in foster care

Roughly one in 10 students in NYC are homeless or live in temporary housing. To help homeless students, Adams has committed to ensuring high-speed internet access in every homeless shelter.

For youth in the foster care system, who are among the system’s most vulnerable, Adams would develop a mentorship program while also investing in employment programs.

Child care access

While New York City has made dramatic strides in expanding access to preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds, challenges remain for many working families.

It can still be a struggle to find quality care for younger children. New York City has an estimated 15 slots for infant and toddler care per 100 children. Capacity went down in middle-income communities between 2011 to 2017, according to the advocacy group Raising NY.

And even those with children in the city’s free pre-K programs may face a child care crunch after the traditional school day ends around 2 p.m. and during summer break. City-subsidized preschool programs have pushed for more seats in centers that provide longer hours and care year-round.

Adams called himself a “big believer” in opening up school buildings beyond the regular day, pointing to his efforts as Brooklyn Borough president to give free space on school campuses to organizations that provide after-school programming. But he did not have specific plans for providing extended hours for child care.

Child care affordability

The expansion of universal pre-K for 4-year-olds saves New York City families an estimated $10,000 a year, according to the de Blasio administration. More and more students are also enrolling in free preschool for 3-year-olds, as the city expands its 3-K program to every school district next year. De Blasio is relying on one-time federal stimulus for the latest expansion, which still leaves the city about 20,000 seats short of reaching every 3-year-old.

Still, care for younger children remains one of the most expensive line items in families’ budgets, accounting for 31% of median household income for those with young children. In some Bronx neighborhoods, the cost can consume 65% of a household’s income.

Meanwhile, a Byzantine approval process and bureaucratic backlog in getting families approved for subsidized care leave many waiting for vouchers to help pay for child care — even while seats in centers go empty.

Adams hopes that providing free or low-cost space for child care programs will result in cost savings that get passed on to families. But he also wants to expand the city’s earned income tax credit, though he does not say by how much. Adams also proposes to expand the voucher program, but his plan doesn’t say by how many slots or whether eligibility might change.

As for the city’s current voucher landscape, Adams said the city needs to do a better job communicating with families about availability. He suggested tapping into the city’s census outreach teams, which hosted teach-ins and conducted phone- and text-banks to help spread the word in ways that resonate across languages and cultures.

“We should be using these teams year-round to continually push out information,” he said.

Early childhood education workforce

Some preschool teachers who work in the city’s privately run, publicly subsidized pre-K programs are paid dramatically less than their counterparts in public schools, which can cause retention and recruitment challenges for programs. New York City has taken steps to address these gaps by boosting some teachers’ salaries by as much as $20,000 after educators threatened a strike.

But large disparities remain. Teachers who work for community-run pre-K sites don’t get the same pay bumps for longevity as public school teachers, and many work longer hours and throughout the summer. And the latest pay deals did not include teachers in certain special education pre-K programs, making those who work with some of the most vulnerable students among the lowest-paid teachers.

Adams said he supports the push for pay parity, and that includes equal benefits for teachers. He said he wants to compensate teachers for their years of experience and provide financial incentives for them to get credentialed but didn’t provide specifics about how to do that.

“It’s almost humiliating what we are paying these professionals,” he said.

He said the city should direct an influx of state and federal money to pay for the increases. If elected, Adams said there should be a clear path towards parity within one to two years of his term as mayor.

After-school and youth programs

Nonprofits that provide after-school and summer youth programs typically have to fight each year for their funding to be included in the city’s budget. Those programs have also been the target of cuts: When the pandemic first struck, the city slashed some 40,000 slots from the summer youth employment program, which provides paid internships to teens and young adults. The mayor’s proposed budget would restore funding for this summer.

Advocates have called for more stable funding for these programs to be built into the city’s budgets, so they and families can plan ahead. Many would also like to see summer youth employment expanded to become universal for any teen who wants a job, and for after-school care to be open to any student who needs it.

As borough president, Adams said he allocated $2 million towards a pilot program to provide community organizations space in school buildings. He wants to expand that program, which will allow nonprofits to provide after-school opportunities like sports, especially in underserved areas. “Because when you really think about the cost, rental of space, use of a space — that is really some of the largest parts of actually having an overhead,” he said.

Adams has also called for schools to be open year-round with services for students and families. In addition, he would like to see a universal tutoring program but didn’t say how he would make it happen.

Reema Amin, Amy Zimmer, and Alex Zimmerman contributed.