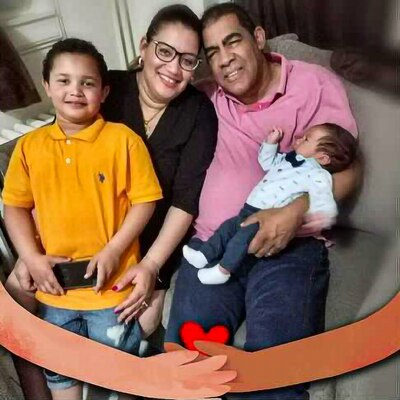

Milagros Reyes’s husband was in the first wave of New Yorkers to succumb to the coronavirus, taking his last breath in their East New York apartment. His death in April 2020 left Reyes alone with her two children, ages 3 and 10.

Reyes called 911 to retrieve her husband’s body, which was quarantined in a bedroom. But hours passed and no ambulance arrived. When the parent coordinator of her fifth grader’s school, P.S. 89, called to check on the child’s absence, Reyes explained the dire situation, setting off a series of messages to the school’s principal, district superintendent, anyone who could help.

Eventually, after 24 hours, paramedics arrived.

“For a young child, it’s a trauma. It wasn’t easy,” Reyes said in Spanish. But she is striving to move forward, leaning on her support system in the school community. “We’re fighting still.”

The grim situation was not the only time a P.S. 89 family struggled to have a relative’s body removed from a home. Those crises served as an early warning of the devastation many members of the community would experience and foreshadowed the ways in which the school would respond with an all-hands approach.

At P.S. 89, an English/Spanish dual language pre-K-8 school in Cypress Hills, the pandemic caused immense damage, including the deaths of loved ones, job losses, mental health challenges, and significant disruptions to student learning. Now, as infection rates plummet and officials promise a return to in-person learning for all students this fall, principals are grappling with how to fully reopen in September while addressing the deep emotional wounds and learning gaps students are facing.

For many families, the emotional scars and learning disruptions are intertwined. Reyes’s initial concerns were about survival after the death of her husband, Patricio Mendez, a taxi driver who enjoyed playing dominoes, Monopoly, and dropping his stepson off at school every day.

Suddenly the sole breadwinner after seven years of marriage, Reyes saw her work as a hairdresser dry up during the pandemic, and the family had to move. The upheaval quickly impacted the education of José David Sime Reyes, a fifth grader who was learning remotely full time and often missed virtual classes.

P.S. 89 officials went out of their way to re-engage José David, making special accommodations for him to return to the classroom even after the city’s deadline to sign up for in-person instruction closed, and offered him additional small group tutoring. The 10-year-old is making academic progress now that he’s back in the school building, though Reyes has started inquiring about counseling for him — and for herself — to help process everything they’ve been through.

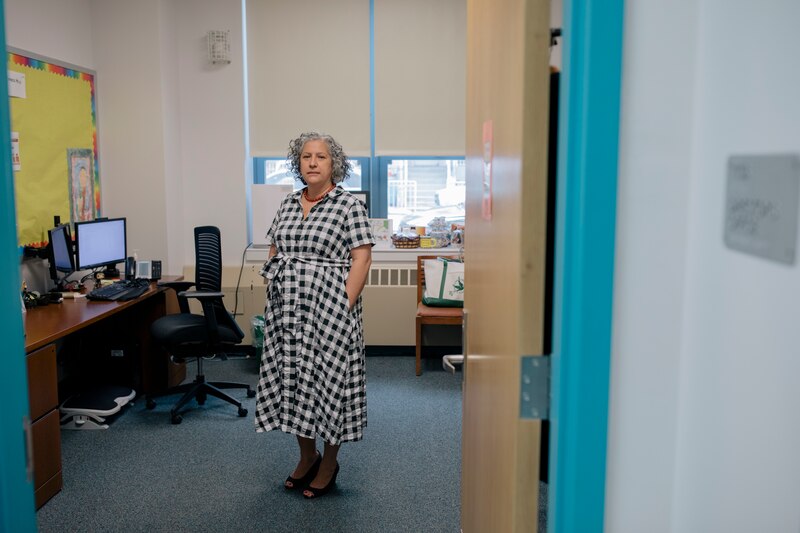

The staff at P.S. 89 knows the trauma and disruption of the past year will linger. As a school that has focused for years on fostering deep ties with families and deploying wraparound services, Principal Irene Leon is optimistic in the school’s ability to meet the moment. But with no tried-and-tested roadmap for this situation, Leon is drawing up one of her own.

“It is overwhelming to think about what the needs are going to be next year when you have everyone in the building,” Leon said. “How do we rebuild a sense of community?”

Road to recovery in the new school year

Since March of 2020, roughly half of the school’s students have been learning completely virtually, disrupting social rhythms and making it difficult for teachers to get to know their students. As city officials plan to require all students to attend school in person this fall, Leon is planning to waste no time recreating a sense of belonging.

P.S. 89 will launch a weeklong set of outdoor team-building activities at the nearby Highland Park, a space where the school can gather more of the community at once, given uncertainty about social distancing rules within schools this fall. She hopes the outdoor activities will ease students back and help them form social bonds that may have atrophied during the pandemic.

Those activities will also give the staff a sense of where students are emotionally and what their interests may be. Although P.S. 89 has a longstanding advisory program for its middle school students, Leon is hoping to tweak the program to group students more intentionally by their passions or needs based on what staff glean in that initial week, boosting the odds that students will quickly form bonds with each other and at least one caring adult.

Once they settle into classrooms, some will find they have two teachers instead of one, thanks to a boost in the school’s budget and money that Leon was able to roll over from last year. The school plans to deploy the additional staff to reach students in grades K-2, so that most of them will take classes that are co-taught, a popular model for serving students with disabilities that is rarer in traditional classrooms. As students will return at widely varying reading levels, with some struggling to master letters and their sounds, Leon is hoping that additional teachers will work with students who need extra help while also nudging along students who are farther ahead.

After a twice delayed school year and frequent closures due to positive coronavirus cases, school officials are also trying to build in ample time to catch students up. P.S. 89 is planning to assess students at the beginning reading and math sequences, leaving as much as a week or two between each unit to tackle material students may have missed the previous year.

“The year was shortened, no matter how you look at it,” Leon said. “It’s important that we address those skills that they missed that they haven’t mastered.”

But Leon isn’t measuring the success of this fall primarily on how quickly teachers can catch students up, or whether test scores rise. She said the truest measure of the school’s success next fall is about how students feel when they walk through the school doors: “The biggest sign is that kids are happy,” she said.

There are still a dizzying array of unknowns that will shape the coming school year. The city has earmarked $500 million for an “academic recovery program,” though it is not yet clear how that will filter down to schools.

The school may receive additional funding to become part of the city’s official “community school” program, which provides wraparound services similar to what P.S. 89 has been providing for years — though the school will likely not find out until later this summer.

At the same time, key details about how schools will operate this fall are up in the air, including health and safety rules. Those regulations could have big implications since they will determine how many students fit in a room, which affects scheduling and how many teachers a school needs.

And there are other immediate planning needs, including an expanded summer school program that launches next month and which many principals like Leon are responsible for organizing.

“It just takes a lot of planning to do it well, and I feel like I’m doing two jobs right now,” she added.

Student mental health includes working with families

P.S. 89 may be better situated than most schools to tackle the emotional and academic needs students will have in the fall. Its deep relationships with parents proved essential during the pandemic and may be a key to its recovery.

Founded in 1997 by a group of parents in concert with a local nonprofit organization, P.S. 89 was an early pioneer of the idea that schools could help knock down out-of-school barriers to learning like hunger or unstable housing by directly embedding wraparound support and social services. The school’s partnership with the Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation gives families easier access to housing services, job training or other social support. The organization also runs P.S. 89’s after-school program.

“We have been doing all of this for more than 20 years, we were prepared, we knew our families, we knew what type of questions to ask,” said Sasha Rincon, a guidance counselor.

The school also has the benefit of a unique leadership structure with a parent co-director in addition to a parent coordinator, who helps orient families and organize workshops on topics like healthy eating.

This past year, the school bolstered its staff to help meet families’ needs, including a new social worker in addition to its two existing guidance counselors. Rincon is already laying out plans this coming year to make sure students get the support they need outside the classroom, and she’s anticipating more acute challenges with following directions, motivation, bullying, dealing with romantic rejection, and processing grief. She’s looking forward to restarting the school’s peer mediation program, where students take the lead in resolving interpersonal conflicts.

Based on what school staff have learned about students’ individual circumstances this year, she’s already identifying students who may need counseling, including those in temporary housing, a group she expects will be larger this year as the economic fallout will continue to reverberate in a neighborhood already suffering from housing instability. She’s hoping to partner with the city’s health department to run a group focused on grief for a handful of students who lost parents or faced other trauma including abuse.

Still, efforts to address trauma and help students catch up academically can only work if they actually show up.

The school has historically posted impressive attendance rates, despite a high-needs population: About 41% of the school’s students are English learners and 91% come from low-income families, far higher than the city average.

Before the pandemic, about 11% of the school’s students were chronically absent, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year, according to city data. That’s significantly lower than the citywide chronic absenteeism rate of about 21%.

Despite its track record of high attendance, P.S. 89 found itself in a similar situation as other schools, struggling to keep all of its students engaged over the past year. Although attendance remained high on paper, some students were missing a significant amount of virtual instruction. (Any interaction with the school on a remote day, however brief, meant a student was counted as present, according to the city’s policy.)

As some middle school students began skipping morning classes, P.S. 89 staffers conducted wake-up calls. It was often difficult to reach students directly, especially those who were home alone and didn’t answer their phones, Rincon said. As work dried up or parents struggled with the logistics of remote learning while holding down jobs, some students moved out of Brooklyn or returned to their home countries such as Mexico, Ecuador and the Dominican Republic, with a handful of these children learning remotely from outside the country. (In all, the school’s enrollment fell about 4% this year, in line with the city average.)

Even though school officials had resisted attendance incentive programs, the school launched one for the first time, with rewards for improved attendance like pencils and hoodies — or, in some cases, McDonald’s and Amazon gift cards.

Come September, students won’t have the option to learn from home, which has sparked criticism from some parents across the city, who said they weren’t consulted before the mayor changed his mind about the need for virtual options, and want to ease back into classrooms at their own pace or simply see advantages to remote instruction.

For her part, Leon indicated that parents at P.S. 89 have not clamored for a remote option, and multiple families said they are looking forward to sending their children back to school in person full time.

“I think parents want to come back,” Leon said. “I think the kids want to come back.”

Jumping in with hands-on projects

Many crucial decisions about how to welcome students this September will fall to teachers.

P.S. 89 art teacher Elizabeth Velazquez is beginning to think about what her classroom will look like next year — and how to restructure her lessons to engage students who may have had negative experiences with school this year.

Instead of beginning with structured lessons about specific artists or techniques, she’s planning to just give her students space to draw, paint, or make collages on their own.

“I feel like they’ve been held back from materials and play for so long, like playing outside, playing with each other, they need that movement,” she said. “I want them to immediately come into the classroom and start making things.”

Remote instruction was particularly difficult for art teachers like Velazquez, who couldn’t count on families having materials at home. She coached them to make paints with cabbage, turmeric and other household items, and noted some students found art as an outlet for the pain and confusion they felt during the pandemic. She also took advantage of the remote setup to make it easier to attract guest speakers, including George Ibañez, a well-known graffiti artist who has deep roots in New York.

For many students, though, art class felt optional, especially those who were overwhelmed by the pandemic and keeping up with virtual assignments in other classes. Velazquez was also pulled in different directions this year, as complicated scheduling arrangements and safety rules meant that she also helped facilitate everything from gym to humanities classes.

Velazquez is hoping that unleashing students on blank pages will help ease them back into the classroom and spark a little joy. It’s an experiment, and how her students respond remains uncertain. But if there’s one thing she took away from this past year, it’s that she may not have complete control over how the year unfolds.

“I’m not sure exactly how things are going to be,” she said. “I’m holding on to the joy that I know exists with my students and bringing that to confront any of the challenges that come into being in this new year.”

Christina Veiga and Amy Zimmer contributed reporting.

Chalkbeat produced this Pandemic 360 series in partnership with Univision 41.