Social media has the power to inspire in ways big and small. But engaging online also means resisting comparisons.

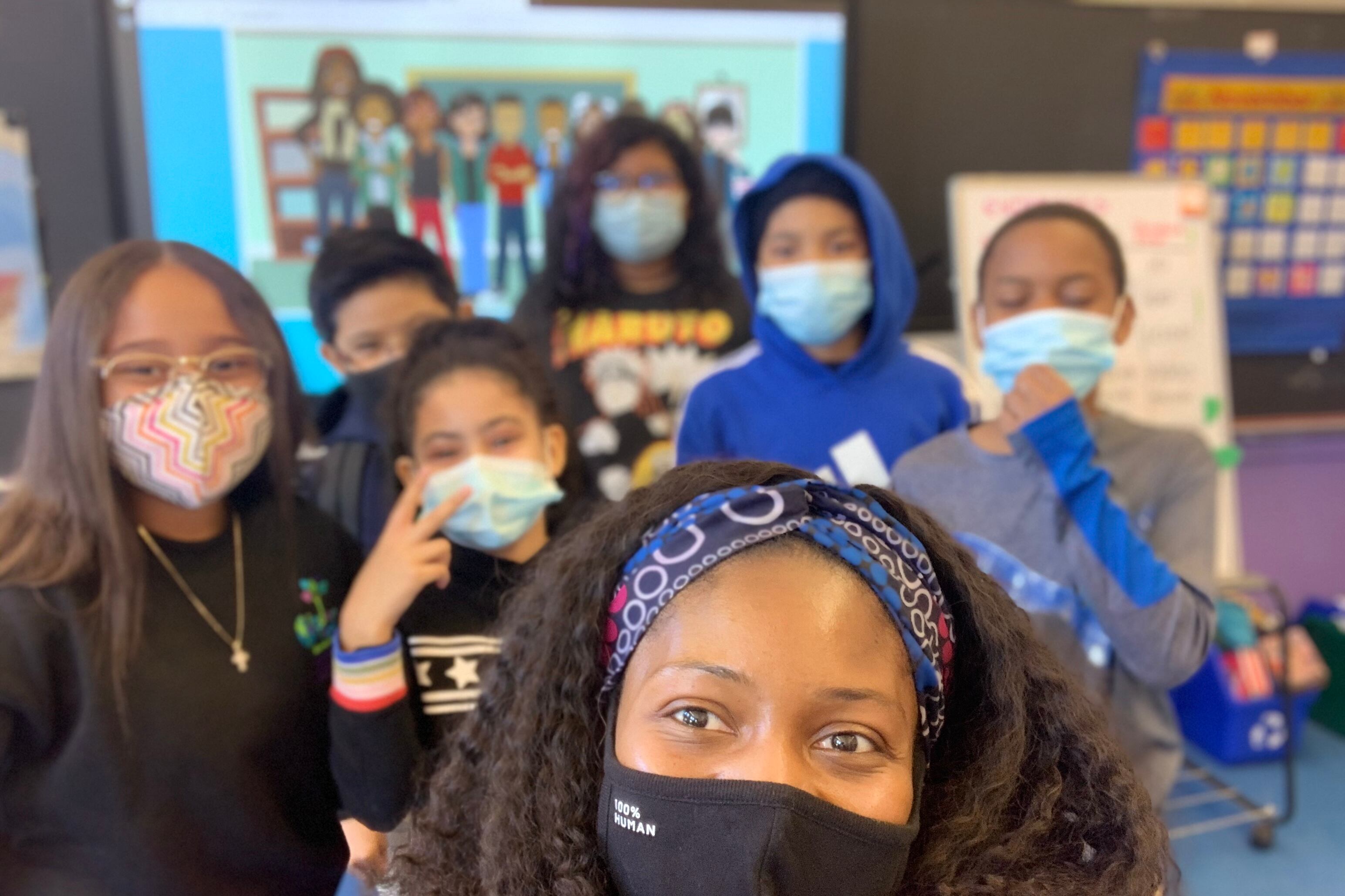

That goes for young people who have grown up with social platforms and for their teachers who have learned to embrace them, too. “Especially now with social media, where everyone is posting their classrooms and teaching practices online, it’s so easy for educators to fall into imposter syndrome and to doubt our talents,” said Islah Tauheed, who teaches fifth grade English Language Arts at P.S. 567 Linden Tree Elementary School in the Bronx.

Which is why she takes comfort in the words of the feminist writer Audre Lorde about defining herself for herself, rather than according to others’ expectations. If that means her classroom is a bit louder or messier or more musical than that of her colleagues, that’s more than OK. “I don’t teach for likes or for followers or to post pretty pictures on Instagram,” Tauheed said. “I teach for the children in front of me, so they feel safe and loved and affirmed in this classroom space.”

Tauheed spoke recently with Chalkbeat New York.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What led you to a career in education?

I truly believe I was born to teach. My mother was a special education teacher. Other kids would skip school to go to the mall. I would skip and come to my mother’s class. Her colleagues were my “aunties.” Like other kids, I played school as a child, but by the time I was 9, I went to my mother in distress because I was worried I wouldn’t have enough credits to graduate and become a teacher. She laughed and assured me I had plenty of time. A career in education also continues the legacy of my grandparents, who were denied access to equal education. As a result, many of my grandparents had trouble reading and writing. When they had children, they were strong and vocal advocates in my hometown for public education. My grandmother was often featured in my hometown’s newspaper for comments she made at city meetings. I very consciously carry my grandparents’ mission as I walk in my mother’s footsteps while simultaneously forging my own path as an educational leader.

I read something you wrote about radical empathy. Why is empathy a radical act, and how do you teach students to be empathic?

I read this quote from the writer Isabel Wilkerson:

“Empathy is not pity or sympathy in which you are — pity, you’re looking down on someone and feeling sorry for them. Sympathy, you may be looking across at someone and feeling bad for them. Empathy means getting inside of them, and understanding their reality, and looking at their situation and saying not, ‘What would I do if I were in their position?’ but, ‘What are they doing? Why are they doing what they’re doing from the perspective of what they have endured?’ And that is an additional step. There are multiple steps that a person has to take to really be open to that.”

Empathy is not passive like pity. Empathy requires questioning oneself. Empathy takes a willingness to shift your mind into perspectives that aren’t your own. Empathy is an action, and I think all actions that you take that lead you out of your comfort zone are radical.

When I taught first and second grade, I assumed teaching empathy would be easy because I thought little children were naturally empathetic. However, they are very much still in their ego phase. A lot of the teaching is centered on actively listening. We practiced on picture book characters. We practiced identifying how the character was feeling and how we could tell. Last, we wrote and role-played words we could say or actions we could take to support that character.

How do you approach current events in the classroom?

Since going remote in 2020, there have been so many big events that came up, like the Breonna Taylor verdict or the presidential election. This year, I have used Sara K. Ahmed’s “What’s in Your News” lesson from her book “Being The Change.” I love the framing because students have a chance to show us exactly what’s on their minds instead of us making assumptions. Reading through their responses gives me a starting point for the conversation.

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

Fun fact about me: I never went to public school! I went to a private Muslim school from preschool to 12th grade. I went to school in my hometown of Newark. My mother was one of the founders of my elementary school. All of my teachers were Black, the nurses were Black, the principal was Black. There was a large focus on celebrating Black history.

It shaped me in ways I didn’t realize until I was an adult and realized that most Black people don’t have this experience. I never had to question who I was at school. I never had to question whether I was being treated differently because of my race. I never experienced tokenism. As a result, at a young age, I was very confident in who I was and that my skills and accomplishments were earned of my own merit. I didn’t limit my dreams because I had representation right in front of me.

As a result, I am adamant about creating classroom spaces where students can thrive while being themselves. Even more than instruction, building that safe, loving classroom culture is my priority. I want students to have that strong sense of confidence and belonging that I had.

What’s one thing you’ve read that has made you a better educator?

Honestly, tweets and texts. Tweets from Lorena German, Aeriale Johnson, and Akiea Gross have been especially influential this year. Lorena and Aeriale remind me that “learning loss” is a myth and that our students are learning in so many ways this year. Educators just have to give students the freedom to show what they know beyond the constraints of state exams or curriculum essays. Akiea has pushed me to be more inclusive in my speech by using non-gendered language and checking my resources to make sure I’m not leaving out contributions of queer people of color from the narratives I’m sharing.

What’s the best advice you ever received — and how have you put it into action?

”If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” — Audre Lorde.

Especially now with social media, where everyone is posting their classrooms and teaching practices online, it’s so easy for educators to fall into imposter syndrome and to doubt our talents. While I will never diminish the voices and needs of the students and families I serve, I have to define my style as a teacher for myself. I have to teach in the style that is authentically me. I have to be myself and teach like myself, knowing that the things I carry with me are my assets. This includes using African American Vernacular English, or AAVE, in my instruction. This includes playing my grandfather’s jazz music as children complete classwork. This includes having a classroom that’s a little noisier and a little less put together than people may expect an elementary classroom to look. I have to constantly reflect on why I teach. I don’t teach for likes or for followers or to post pretty pictures on Instagram. I teach for the children in front of me, so they feel safe and loved and affirmed in this classroom space.

What do you want people to know about your students?

They are brilliant, thoughtful, inspiring, and hopeful. When I asked them what they were most proud of this year, they replied that when the pandemic began, they were so nervous to learn from home because they are used to being in a room with a teacher at their side to call on whenever they need help. However, they got through the year with levels of independence they weren’t aware of. They are very proud of that. I also asked them about their hopes for next school year, and each student wished for a teacher who is kind and “sweet” and understands that they’ve spent the entire year remote. They want their teachers to be patient as they re-enter the buildings and understand if they do things more slowly.