Maud Maron was taken aback during her son’s recent fifth grade graduation when school administrators took a moment to acknowledge that the school building sits on land once taken from Native Americans.

“I was like, ‘yes, that is true,’” Maron recounted. “But, as it turns out, for the better part of human existence, we have stolen land from each other.”

Maron, a public defender who this year ran an unsuccessful campaign as a Democrat for New York City Council, is part of a growing contingent of parents and educators who are speaking out against the ways race, ethnicity, and diversity are addressed in K-12 schools nationwide. (Maron is still running as an independent.)

“There’s this incessant fixation on white guilt and using the terms ‘colonial’ and ‘settler’ to describe white children who are in a classroom,” said Maron, a Community Education Council member who has four children in New York City public schools. “There’s movement afoot that is changing the way our children are being spoken to.”

The changes Maron is concerned about range from discussing racial justice in academic classes (she says this takes away from time that should be spent on academics) to acknowledging that the country violently forced Indigenous peoples from their land (she finds such mentions unnecessary).

These concerns and others are often bundled together under the banner of critical race theory, a more than 40-year-old academic framework for studying institutional racism. Once only taught in higher education, CRT has become a political flashpoint, dominating headlines and school board meetings ever since the Manhattan Institute’s Christopher Rufo claimed that CRT had infiltrated the federal government and public schools, leading President Donald Trump to issue an executive order barring racial sensitivity trainings from the federal government.

While criticisms of CRT are loudest in states with conservative legislatures — some 26 states have followed Trump’s example and sought to limit the teaching of CRT, racism, or ethnic studies in public schools — the conflict has made its way to New York City.

The education department maintains that CRT is not taught in the city’s public schools, but some parents disagree. Maron, who learned about CRT while in law school, argues that the concepts from the framework are influencing the way teachers educate their students.

As an example, she pointed to a friend’s high school-aged son who was recently in a precalculus class on Zoom that discussed how the city’s subway system is implicitly racist.

“Five years ago or 10 years ago, I don’t think you would have had all of this discussion about racial justice,” she said.

Critical juncture for New York City schools

In March, New York private school parent Bion Bartning launched a national nonprofit organization, Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism, or FAIR, after he learned that Riverdale Country School, where his children attended, had developed antiracist initiatives. Upset by the school’s new “orthodoxy” about race, Bartning pulled his children out of the school. FAIR has since lobbed criticism against CRT and broadly advocates for a “human first” mindset — something critics liken to an “All Lives Matter” mentality. (All Lives Matter was a response to the Black Lives Matter movement. It sought to delegitimize the notion that Black people have been systematically discriminated against in the U.S.)

FAIR has chapters across the country, including one in New York City co-led by Maron and Yiatin Chu, a public school parent and member of the Community Education Council covering Manhattan’s Lower East Side and East Village. Both Maron and Chu also lead PLACE, or Parent Leaders for Accelerated Curriculum and Education, an organization that formed partly in protest of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s push to overhaul admissions to the city’s specialized high schools, which enroll few Black and Latino students.

Although CRT is not taught in NYC public schools, the city recently pledged multiple efforts to create a culturally responsive curriculum. Last week, city officials announced a $202 million effort to standardize English and math instruction through its universal Mosaic curriculum, which is meant to represent the diversity of the city, and the City Council this year approved $10 million in funding for an “education equity action plan” that calls for the creation of a K-12 Black studies curriculum. The education department also released a curriculum supplement in the spring that centers LGBTQ voices.

The conflict over CRT comes at a critical juncture in New York City’s education system. In September, students will return to classrooms after more than a year of disruption and chaos during the COVID pandemic. And come January, a new mayor will take control of the nation’s largest school system, managing a massive infusion of COVID relief funding and addressing the racial and socio-economic disparities that the pandemic brought to the fore.

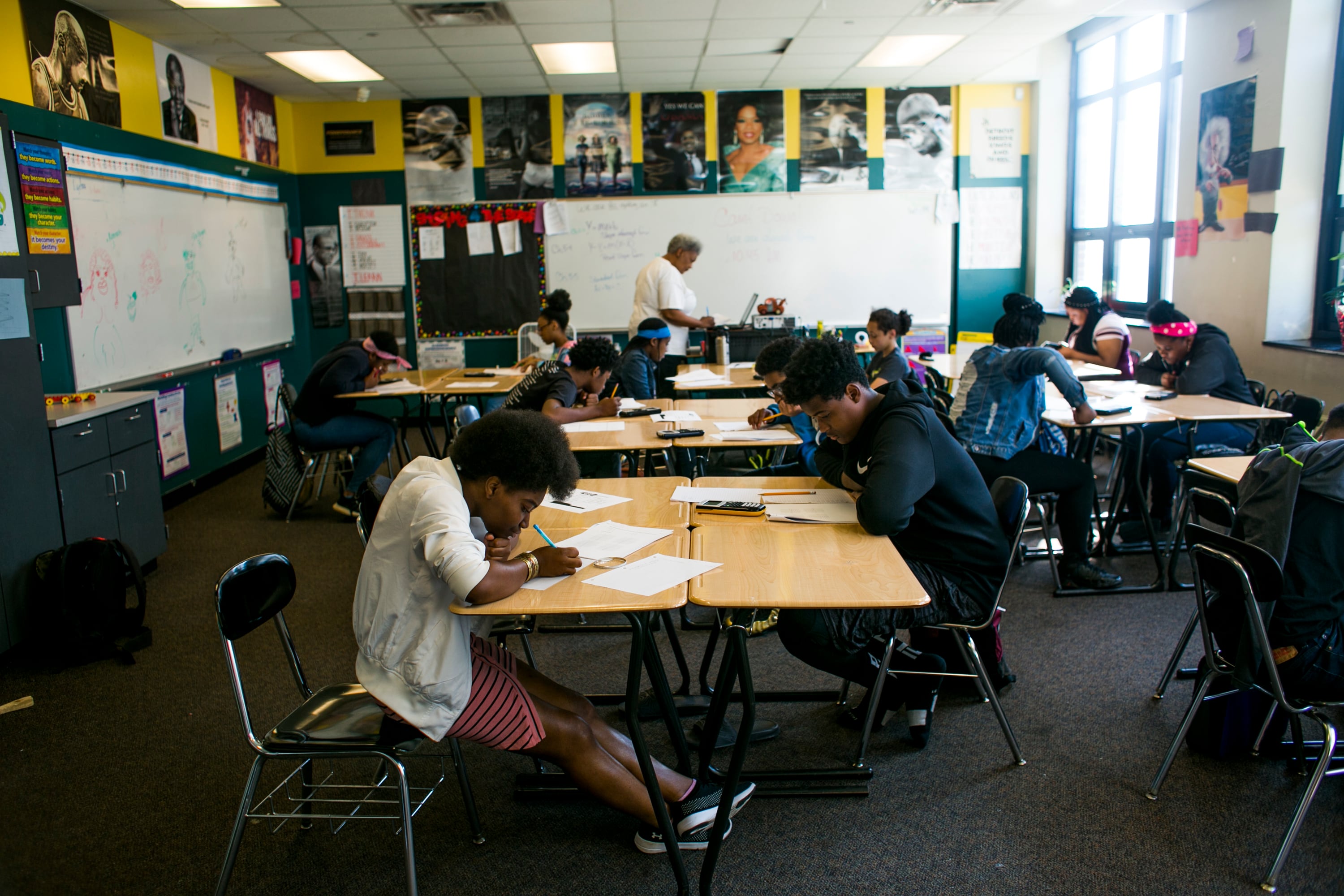

As tensions flare over racial justice nationally, the city must likewise grapple with how race will figure into the path forward for public schools. For some parents, like Maron, extended classroom discussions on race feel unnecessary, even counterproductive, to student success. Others believe that examining the nation’s history of oppression is integral to engaging the city’s nearly 1 million students, more than 80% of whom are students of color. The fight has become so polarized at times that it has left little room for civil discourse, preventing parents from hearing each other’s point of view.

The rise of critical race theory

About two months ago, Zakiyah Ansari was sitting on her couch watching television when she heard the newscaster mention critical race theory. Over the next few weeks, she saw the phrase pop up more frequently, on MSNBC, in emails with parents, and on social media. She did not know exactly what CRT was, she admits, but she knew it was something to watch.

“My ears perked up because I’ve been doing this work for so long, and I knew people were coming after something that is centered in justice,” said Ansari, advocacy director for the Alliance for Quality Education, which has been pushing for antiracism in education.

While Ansari learned more about CRT, she began to see that it was being used as a catchall term to define some of the work she had been doing for years to uplift marginalized voices. She saw criticisms of CRT as an attack on recent efforts to integrate anti-bias training and racial justice initiatives into education.

In 2018, after several years of advocacy on the part of parents and others like Ansari, New York officials allocated $23 million to support anti-bias education for the city’s teachers. Now, the city is investing $200 million to create a culturally responsive curriculum expected to be used in the city’s roughly 1,600 schools by the fall of 2023. And last month the city approved a budget with $10 million set aside for a K-12 Black studies curriculum along with a professional development program to implement it.

Amid these changes, those critical of bringing race into the classroom have become louder, with many taking on leadership positions. During the recent Community Education Council elections, a slate of candidates endorsed by PLACE won seats. These parent-led councils have the power to change or create school zones, and they are a primary mode of bringing parent voices to the attention of the schools chancellor. Several of them have also led integration efforts, something that PLACE has historically not supported.

“What we are hearing from some of these new parent leaders [endorsed by PLACE] is that we need to stop talking about race and talk about academic excellence, as if those are not the same thing,” said Ansari. “That’s a problem.”

The crux of the conflict

Ansari’s comment points to the fundamental disconnect between people who are lambasting CRT — or something they are labeling as CRT — and those who are pushing for a culturally responsive education. While the former view anti-bias training and curriculum changes as a distraction from academic rigor, the latter say it is a necessary ingredient to drive student success.

At a press conference announcing Mosaic, Porter said “students are more engaged when they see themselves in the lessons and the curriculum. [Mosaic] will be a comprehensive curriculum that accelerates student learning and prepares them for success in school and in life.”

While some groups, such as the Coalition for Educational Justice, lauded Mosaic as a critical step in standing against racism and oppression, others decried the investment. PLACE leader Chu tweeted in response: “What excuses will be left after we spend ‘historic’ $$$$ w/CRSE [Culturally Responsive & Sustaining Education] standardized curriculum and half of NYC kids still do not read at grade level?”

In a statement, PLACE referred to “including and affirming” as “a nondescript platitude that, while perhaps well-intentioned, does nothing to improve academic outcomes.”

Chu and others argue that NYC schools are failing their students: Less than half of third grade students scored proficient on 2019 state math and reading assessments. PLACE believes that fixing the city’s failing schools requires redoubling efforts on academics — creating rigorous curriculums for all students and investing more money in gifted and talented programs.

PLACE also denies that systemic racism contributes to New York City’s underperforming public schools. “To say that students aren’t performing because our schools are racist is just too blunt and not true,” Chu said in an interview.

Meanwhile, proponents of culturally responsive education say that schools are disproportionately failing students of color, a problem that stems from structural racism. Creating a culturally responsive education, they say, is necessary for students to succeed.

“We can’t improve education, rigor, and all the other things that we’ve been talking about if we have structural barriers in the way,” said David E. Kirkland, executive director of the NYU Metro Center, which researches solutions for issues facing public schools. “We have to have these courageous conversations.”

“One of the main reasons that we see inequity is because our children don’t know who they are and where they came from. They don’t understand their history,” said City Council member Adrienne Adams, who championed the education equity action plan.

Recent research suggests that student engagement is higher when classes include conversations about racism and bigotry. For instance, one study found that Black boys who took a class focused on Black history and culture were less likely to drop out from high school. And another study in Tucson found that a Mexican American studies course boosted test scores and high school graduation rates.

A story of racial division or racial triumph?

Last month, FAIR released a set of learning standards meant to provide guidance for teaching and learning about the history of people from diverse cultural backgrounds in the United States. The standards, called “pro-human,” include specific grade-level outcomes, or expectations, for student development on “humanity,” “diversity” and “fairness.”

For instance, students in grades 3-5 are expected to be able to “discuss specific people from history who drew power from their humanity, culture, and American ideals to fight racism and intolerance.” And high school students are supposed to know how to “treat each person’s life and story as irreducibly unique.”

Maron pointed to the learning standards as evidence that FAIR is not against teaching the history of Black people or Indigenous peoples; what they are against is reducing individuals to their race.

Although Maron could not confirm whether the learning standards were shared with the New York City education department, she said their purpose is to address parent concerns by helping guide conversations on diversity.

But for critics, the standards symbolize the political right’s push to gloss over the less forgiving parts of American history.

“If students ask questions about racism and discrimination, they will say that in the past, things happened at an episodic level, not at a structural level,” Kirkland said. “And that the story of America is not a story of racial division but of racial triumph.”

“It’s not that we are not a human race,” Kirkland continued. “It’s that the country was constructed on the idea that there are people of different races, with whites on the top and Blacks on the bottom. And that narrative continues today.”