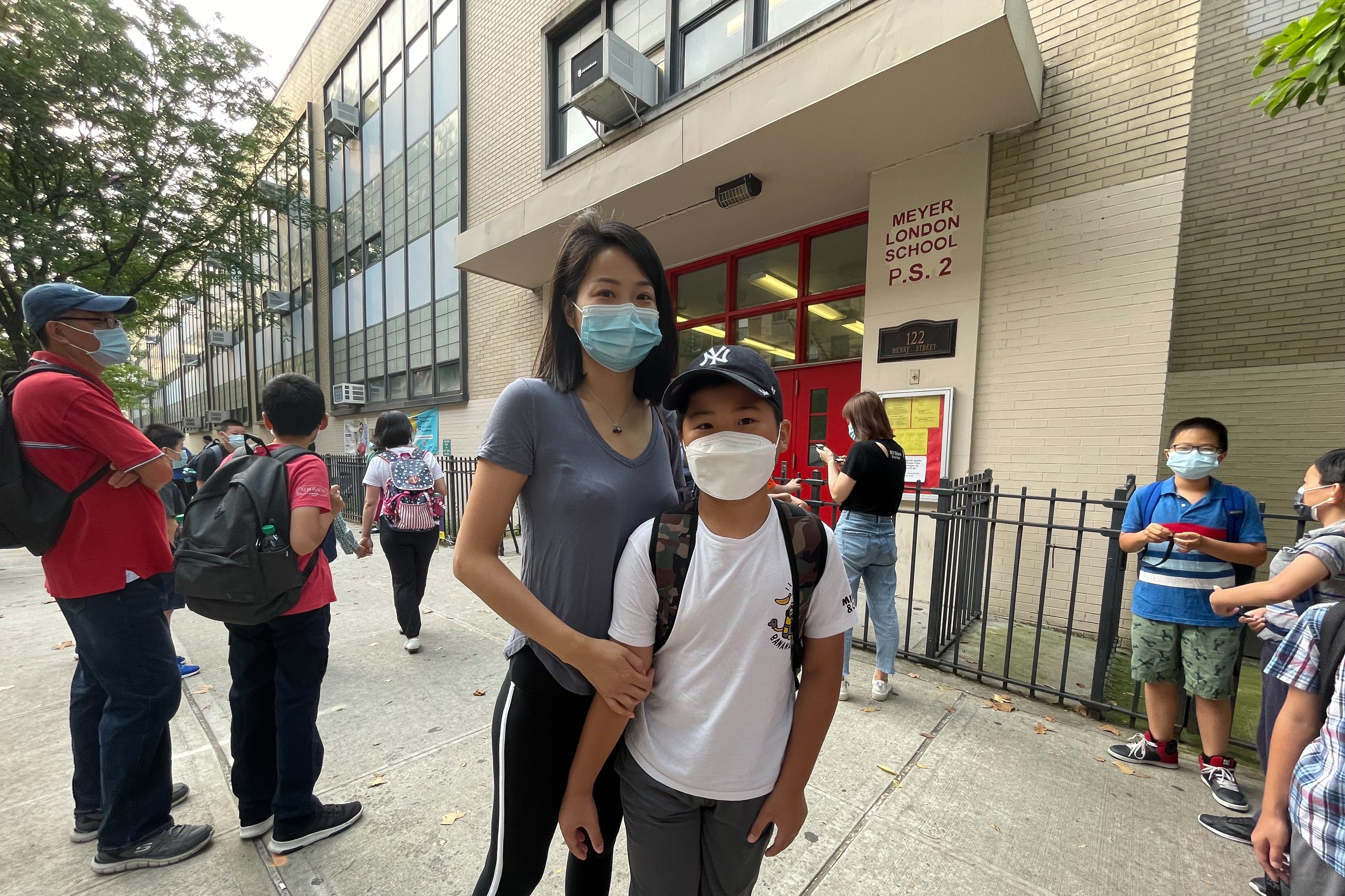

Excitement, nervousness and confusion were palpable on Henry Street in Lower Manhattan, where over a hundred parents lined up next to P.S. 2 with their children on Tuesday morning, day one of the city’s summer school program.

Some parents, like Victoria Yang, were excited that the city had opened the summer program, called Summer Rising, to all students, not just those who were behind academically. “If [my son] stays home, he’ll just play on the iPad all day long,” Yang said, adding that she was grateful her son, a rising fourth grader, would get a chance to interact with other kids after a school year marked by limited peer-to-peer interaction.

Students, too, were enthusiastic, jumping up and down and exchanging waves and jokes with friends whom they spotted in a line that extended for more than 150 feet. Other parents, though, seemed frustrated.

After completing what several parents called a confusing enrollment process with electronic glitches, parents were stuck waiting in a long line, only to be told by administrators that their children were not yet assigned a classroom.

More than 200,000 students are enrolled in summer programming, according to city figures. About 98,000 students in kindergarten to eighth grade are participating in programming that includes a mix of academic work and enrichment activities in the afternoon. Roughly 14,000 students in grades K-8 were mandated to participate because of their academic performance; about 2,000 of them opted to participate remotely.

About 80,000 high school students were enrolled in the Summer Rising program. Another 23,000 students with disabilities, who are entitled to year-round schooling, were expected to participate in summer programming as well. Officials said 10% of students and staff would be randomly tested for the coronavirus during the summer program every other week. (During the school year, 20% of students and staff were tested weekly.)

The opening days of summer school represent a test of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s overhaul to summer programming that he hopes will be a model for future years. In light of disruptions to learning caused by the pandemic, any city student was allowed to sign up for full-day summer school, which combines traditional academic offerings with afternoon enrichment activities provided by nonprofit community organizations.

For the second year in a row, the city has struggled to plan and launch its summer offerings, leaving some crucial decisions until the last minute, including how to handle transportation for homeless students and those with disabilities and where to enroll students who had been waitlisted or turned away from sites that were oversubscribed.

It was not until last week that Dolly Del Rosario found out that her son had gotten off of the Summer Rising waiting list and had been placed at P.S. 2, one of the city’s 800 sites for the program. But when Del Rosario arrived at P.S. 2 on Tuesday morning, it seemed that the school was not prepared to accommodate her son.

An administrator told her, along with several other parents, that due to staffing shortages, those students would be sitting in the school’s auditorium all day while the education department worked to supply sufficient staff, according to conversations that were witnessed by a Chalkbeat reporter.

Parents were told that the students in the auditorium would have structured activities to complete under adult supervision, but parents were also given the option to take their kids home on Tuesday and return on Wednesday, when additional staff would be in place. (Education department spokesperson Sarah Casasnovas disputed that students would spend the day in the auditorium and said they would be sent to classrooms.)

According to one administrator at P.S. 2, that location had initially set aside 220 seats. On Tuesday, approximately 370 students were enrolled.

“We have a good team and we are going to make it work,” that administrator said. “It’s a bumpy start, but I know it’s going to be a great summer.”

Last week, city officials began telling principals that summer sites should expect to enroll “all students interested in the site’s program,” including those who had been placed on waitlists, sending more students than some sites were immediately prepared to serve. The directive drew intense criticism from the head of the union that represents principals and other administrators.

On Tuesday, de Blasio said the city saw a “surge of interest” in the program and acknowledged “we had to make some additional staffing additions to be able to keep up.” He added that the staffing situation “may take a few days to all sort out in a few schools, but overwhelmingly I think we’ve got what we need.” An education department spokesperson said there would be “large numbers of subs and staff” on hand in the event that community organizations had more students than they were contracted to serve.

Some community organizations said the opening day of the summer program was going well. Maurice Rawls, who oversees three Manhattan summer school sites operated in partnership with the Grand St. Settlement, said even though two of his sites were oversubscribed, the number of students who actually showed up was manageable.

Rawls’ staff will help oversee the afternoon enrichment portion of the day and deploy a range of activities, including chess, soccer, craft projects and graphic design lessons. The organization will also offer meditation and other opportunities for students to check in and talk about their feelings.

“It is something that is needed after COVID,” Rawls said. “They’re being engaged. A lot of these kids were isolated from their friends.”

Other nonprofits said they were facing a bumpy rollout, with one Queens staffer saying logistical challenges will likely continue throughout the week, as students who might be returning from the three-day weekend will likely continue to drop in over the coming days.

“Now, because the DOE is trying to appease all parents, we are scrambling to order more supplies or amend our planning,” said the nonprofit leader, who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak publicly. “We also have a space capacity because of COVID and the DOE is stretching that very thin. To me that is a big concern.”

Chanté Brown, the division director for Good Shepherd Services, a nonprofit organization operating the afternoon session at 11 different Summer Rising sites in the Bronx, similarly said staffing shortages were a problem across her sites. She had asked for 38 paraprofessionals across the sites, but only 17 showed up. As a result, the ratio of students to teachers, which she said should be 15 to 1, was higher.

“We had to call out some of our staff from our reserves who do other things and tell them we needed them onsite,” Brown said. “It’s a little bit scary.” Brown found herself leading some of the afternoon activities, which included a jazz dance class, an art project and board games.

Brown added that the paraprofessionals are only slated to work until 4 p.m. but the elementary school program runs until 6 p.m. This could pose a problem for some students with disabilities who need individual help.

De Blasio indicated that some bumps were inevitable given the city’s efforts to quickly scale up the program but added that he believes they will be smoothed out.

“This is a big endeavor on top of another very big endeavor, which was ending the school year we were in,” he said. “We definitely had to learn some things to do better based on what parents were telling us, but I feel good that the pieces are coming together now in a way that will work.”