It felt like a race to deliver bad news.

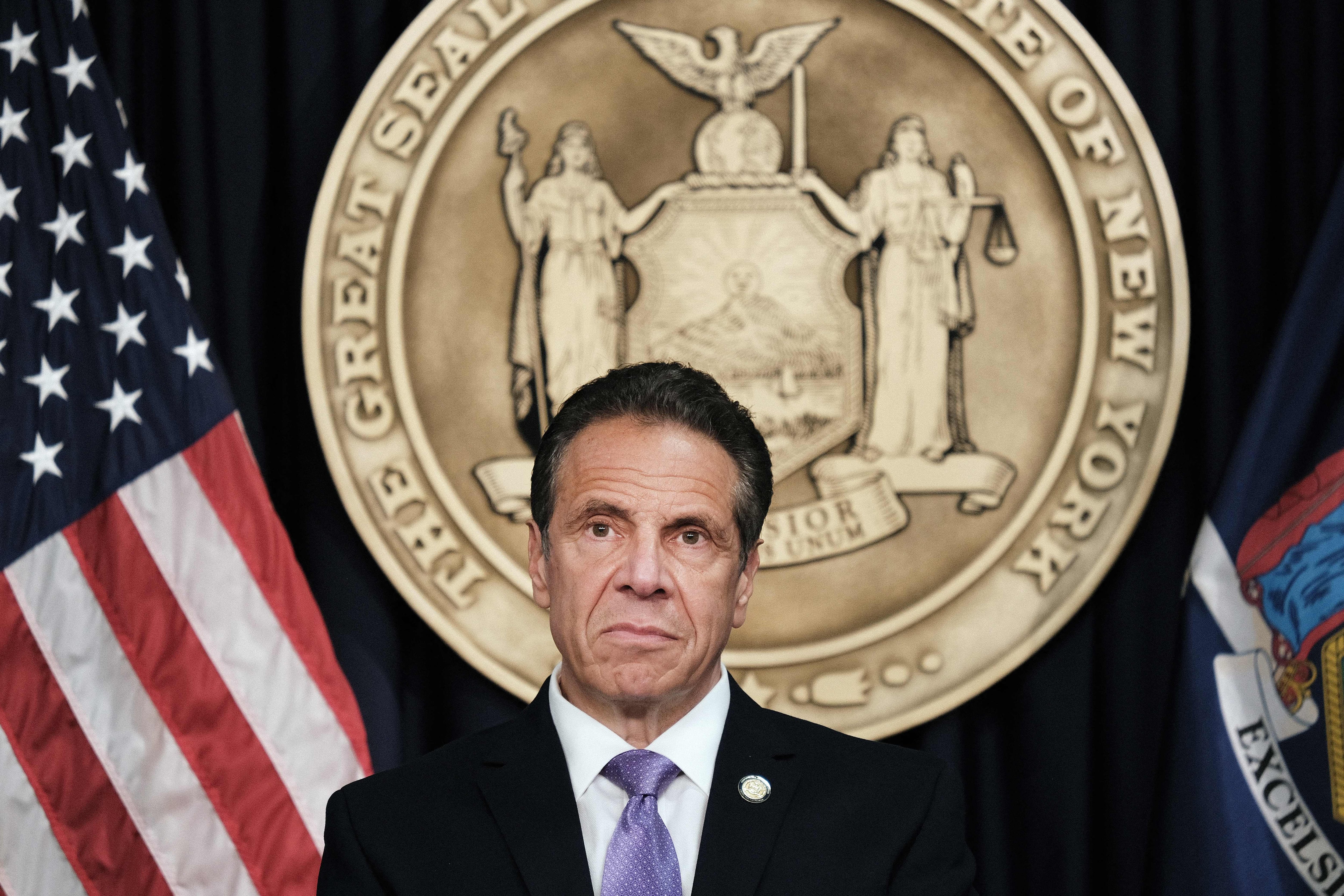

New Yorkers were waking up to the reality of how drastically coronavirus would upend daily life on March 15, 2020, when Gov. Andrew Cuomo said he would leave the decision about whether to close schools up to the state’s roughly 700 school districts.

Hours later, he pivoted, telling New York City officials that they should close early that week and had 24 hours to come up with plans. It was 30 minutes before Mayor Bill de Blasio’s scheduled press conference to announce a closure of the nation’s largest district. Cuomo stole the mayor’s thunder: city schools, he announced, would close.

Seventeen months later, as Cuomo’s political future comes crashing down, his administration has declined to provide any COVID safety guidelines to schools as they prepare to reopen while a highly contagious variant of the virus spreads.

That push and pull is representative of how Cuomo — who announced he would resign following a state investigation that found he sexually harassed 11 women and fostered a toxic work environment — approached education policy over his decade in office. Early on he revealed an aggressive reform agenda only to pull back in the face of backlash, resisted massive increases in education spending only to relent, and made national headlines with a proposal to fund “free college” that was ultimately more flash than substance.

After initially refusing to step down, Cuomo announced Tuesday his departure from office would take effect Aug. 24. His resignation comes after prominent Democrats, including President Joe Biden, and powerful labor leaders, including the state and New York City teachers unions, said he was unfit for office, as well as threat of impeachment. Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul, from Buffalo, will take over and become the state’s first female governor.

Cuomo’s greatest power over schools came through the budget process — affecting funding levels for every public school in the state. His decade in office included some significant early attempts to alter schools across New York and included perennial fights about how much money the state should direct to classrooms.

But with the budget process wrapped up for this fiscal year, the sudden downfall of the three-term governor is unlikely to have an immediate impact on New York City’s schools. Cuomo is also not leaving any big unfinished education agenda items. He has generally focused on other policy areas in recent years, leaving behind contentious fights about teacher evaluations and charter schools, which have fallen out of favor among Democrats nationally. In recent years he has supported union-friendly initiatives such as embedding schools with wraparound services and offering free tuition at public universities.

Moreover, the state’s education department is not controlled by the governor; it is overseen by the Board of Regents, whose members are appointed by the legislature and set education policy for the state’s school districts.

Still, Cuomo did leave a stamp on schools across the state and in New York City, helping to boost the charter sector and playing an outsized role in how much state funding rolled into district coffers.

Here’s what you should know about the education legacies Cuomo leaves behind:

He tried to overhaul teacher evaluations, but that effort fell apart

One of Cuomo’s most aggressive education proposals was an effort to overhaul the state’s teacher evaluation system, which he famously said was “baloney” because virtually all teachers are rated effective despite most students scoring below grade level on state reading and math tests.

He successfully pushed in 2015 to significantly increase the role of state test scores in teacher evaluations. But those changes came as the state’s standardized tests were also shifting to align with the Common Core standards. Educators and teachers unions argued that the tests weren’t designed to measure teacher performance and that many educators were still adapting to the new standards. It also prompted concerns that schools would overemphasize teaching to the tests.

The opposition to the plan ultimately sparked a massive “opt-out” movement across the state in which one in five students boycotted the tests. Those students are more likely to be white and from more affluent districts, and the percentage of test refusals has generally been much lower in New York City. But the revolt had a big political impact.

“Hitching your wagon to state tests didn’t work out well because the public lost confidence in those tests and was wary about them being used for purposes other than what they were designed [for], which was measuring student performance,” said Aaron Pallas, a professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

Cuomo ultimately reversed his stance on using state tests to evaluate teachers, and the Board of Regents placed a moratorium on using the grades 3-8 Math and ELA tests in teacher evaluations. The legislature ultimately scrapped the testing requirement entirely, allowing local districts and teacher unions to hash out what assessments to use.

Cuomo fought bitterly with Mayor Bill de Blasio over charters, and more recently on school reopening

Cuomo’s longstanding feud with de Blasio occasionally spilled into education policymaking — and some of the roots of that dispute can be traced to disagreements whether the state should raise taxes to pay for the mayor’s signature education promise: universal pre-K.

The governor also repeatedly needled the mayor on his resistance to charters, publicly funded but privately managed schools that Cuomo was seeking to expand across the state. When de Blasio took office in 2014, he vowed to rein in co-locations in which charter schools received free space in district school buildings, and even tried to quash a handful that were already in the works.

The governor responded by supporting legislation that ultimately required the city to provide charter schools space free of charge, or else subsidize their rent in private buildings, a significant blow to de Blasio’s efforts.

Early in the pandemic, the two clashed over school reopening and closing decisions, with the governor big-footing or second-guessing the mayor’s decisions. More recently, Cuomo has been content to let de Blasio make politically contentious calls about reopening schools.

Advocates played an annual school funding tug-of-war with the governor

Cuomo initially cut funding for schools when he took office in 2011, promising to rein in state spending and close a large budget gap. Over time he boosted spending, with roughly $1 billion in increases for all districts each of the last few years before the pandemic. New York spends more per pupil than any other state.

But Cuomo refused to fully fund Foundation Aid, a state funding formula that sends more money to high needs schools.

That formula was the result of a long-running lawsuit that successfully argued the state was not providing a “sound, basic education” to New York City schools. The recession hit shortly after the formula was created, eventually leading to cuts. The state never fully funded Foundation Aid, amounting to more than $4 billion for all New York districts this year. New York City officials say they’re owed about $1 billion in Foundation Aid.

Cuomo has argued the state had already fulfilled the minimum required funding from the lawsuit, but that does not satisfy what the formula actually calls for, advocates and education officials have contended. (State law allows officials to tweak the formula as they want every year.) Instead Cuomo attempted multiple times, unsuccessfully, to revamp Foundation Aid. But Cuomo would go on to change his tune about funding, touting the need for “historic” state spending — though still below what advocates and education officials wanted.

State lawmakers passed a budget last year during the start of the pandemic that used federal coronavirus relief dollars to backfill cuts to school districts instead of using them to bolster state aid. As a result, districts like New York City that have higher shares of low-income students were left with deeper funding holes.

But this year, as Cuomo initially came under fire for allegations of both sexual harassment and a cover-up of COVID nursing home deaths, he stunningly agreed to a budget that would fully phase-in Foundation Aid dollars to school districts by 2023, with increases starting this April.

That budget was aided by billions of federal coronavirus relief dollars, as well as a tax hike that progressive Democrats pushed for. Cuomo had previously resisted such a hike, but buckled to it under pressure, said Michael Rebell, the leading attorney on the case that created Foundation Aid and the director of the Center For Educational Equity at Teachers College.

“It is clear as day to me that the only reason the Foundation Aid [increases] got through the legislature and was approved this year is because Gov. Cuomo was in a weakened state,” Rebell said.

Cuomo launched a free college program, but it came with fine print

In 2017, Cuomo announced a first-in-the-nation program that offered free tuition at any of the state’s four-year public colleges. Called the Excelsior Scholarship, it is open to students from households that earn less than $125,000.

The new program was celebrated but it also came with a big catch: students must live and work in New York for as many years as they received free tuition, and if they left, they’d have to pay the scholarship off as a loan. That could result in more student debt or force graduates to stay unemployed in order to avoid the penalty, experts said at the time.

Critics also questioned the program’s requirement for students to take a full-time course load of 30 credits a year or risk losing their scholarship. While that’s the average to graduate on time, it may not be feasible for the very students who need the scholarship, as they may be juggling work or family obligations.

A state spokesperson for the Higher Education Services Corporation, which oversees the scholarship, did not respond with the latest number of students taking advantage of the program or the number of people that have lost their scholarship. An older analysis found that just over 25,000 students had received the Excelsior Scholarship in 2018, a 23% jump from the previous year. That represented just 4% of all undergraduates in New York.