As a new teacher in Arizona 20 years ago, I found myself in the middle of a campaign against bilingual education.

Arizona voters had recently passed Proposition 203 restricting bilingual education and English as a Second Language instruction, as it was called then, following a campaign by the conservative businessman Ron Unz. I was told by seasoned teachers only to speak English to students and to only send letters home in English. Any administrator could write us up for speaking another language, I was told, and I could even be fired.

I worked with other teachers who saw the white supremacy in this initiative, though, who continued to use Spanish to communicate with students and their Spanish-speaking families. That experience taught me that there will always be someone trying to standardize teaching and issue misguided, top-down directives. But it’s my job to provide my students what they actually need — and I need to bring my whole self to the job to do that.

Last year, in my 21st year working in education and after eight years working in school leadership, I found myself back in the classroom, relearning those lessons. It was the fall of 2020, and the students in my mixed-age class of fourth and fifth graders had questions about the history of voting in the United States. How does voting work? What is the “electoral college”? Wait, Black people weren’t allowed to vote? Why did Black people have to march and pay taxes and take literacy tests just to vote?

Mix in the Black Lives Matter movement, and our conversations and history lessons expanded to include discussions about current events, debates, and commitments to using their voices to resist discrimination. Students wrote about “Democracy Heroes,” a term that my co-teacher used to describe folks from various racial, ethnic, gender, and class groups who have fought against oppression.

Virtual learning added more difficulty. When I changed to a mixed-age kindergarten and first grade class, It became clear that picking a picture book that would spark curiosity in a 5-year-old was key to keeping that child’s interest on Zoom. Having that student’s race reflected in the text was one way to do that. And writing? There is no way anyone ages 5-10 will write if they are not interested in the content — and that’s true when they’re getting regular, in-person instruction. Teaching and learning remotely meant that writing prompts had to include our students’ lives and realities.

That is why critical race theory is not something I will shy away from, even as lawmakers across half of our country ban certain kinds of discussions of race and racism.

Using texts that include our students’ lives and realities centers their experiences as raced people, a tenet of critical race theory. By engaging in research about “Democracy Heroes” and using picture books that focus on characters of color, Whiteness is decentered — another educational tenet of critical race theory. Finally, we all thought of how to sustain our cultures and our integrity through storytelling — another educational tenet of critical race theory. Critical race theory is interwoven in all that I do.

It happens that New York City parents are OK with that. I know this because I am also a doctoral student and member of the Urban Education Research Collective at the CUNY Graduate Center. Our project focused on listening to New York City parents voice their concerns and share their perspectives about schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic and the country’s increased focus on racial justice. They told us that more parent and community engagement is needed to shape school policies; that their children’s social-emotional and mental health deserves more attention; and that New York City schools should use a more anti-racist and inclusive curriculum.

Teachers need the freedom to do what we have been charged to do – to educate. As we get deeper into the 21st century, we have to leave the tools of and perceived “normalcy” of White supremacy behind us, too.

To do my job last year, I needed an environment that let me use all of my tools to figure out how to teach reading, writing, and math, and hold space for all of the kids’ questions. I needed space to be a teacher who was racially literate and racially radical, who could both answer students’ questions about the world we live in now and help them imagine a world where racism does not shape their life opportunities.

I had that space, but not all educators do. Please, just let us all educate — and let us be our whole selves.

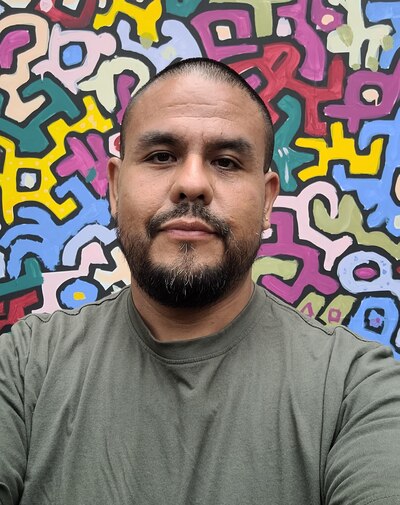

David R. Rosas is a first-generation, bilingual, queer-identified, Indigenous, Native New Yorker from Hell’s Kitchen, pre-gentrification, and is now an assistant principal at the Castle Bridge School in Washington Heights. David has been an educator for 21 years and has worked as a teacher in grades K-7, an instructional coach, assistant principal, and principal in elementary schools. Additionally, he advises pre-service school leaders at Bank Street College of Education and Teachers College, Columbia University.