Inside a century-old red brick building on the edge of Manhattan’s Chinatown, Joanne O’Neill and her custodial staff have been hustling.

In the morning, two hours before students arrived for summer camp, approximately 70 window air conditioning units were flipped on, and all windows – the primary source of ventilation in the building – were opened. Once classrooms were occupied, O’Neill’s team checked carbon dioxide levels, a proxy for a space’s air quality and its concentration of aerosols. Throughout the day, the team would complete other maintenance tasks, such as installing new MERV-13 filters in window units and disinfecting high-touch surfaces like door knobs and light switches. At night, every room had to be properly sanitized. The routine will likely be the same when school opens Sept. 13.

“We strive to get buildings to a point where parents, teachers, and administrators feel comfortable coming in – that’s kind of our mission,” said O’Neill, custodial engineer at P.S. 42, which serves about 500 students from pre-kindergarten through fifth grade. “We’re doing the best we can.”

After COVID upended lives in March 2020, ventilation — whether through mechanical systems, natural air flow through windows, or a combination of the two — emerged as a critical tool to curb the spread of the virus in indoor spaces. The city launched an intensive effort to inspect every classroom’s ventilation system ahead of last fall’s reopening. The resulting ventilation reports were less detailed than many teachers had hoped and showed that many rooms had documented problems with air supply or exhaust components.

The education department has since invested millions of dollars to improve ventilation by, for example, committing two air purifiers to each classroom, installing 110,000 MERV-13 filters to help remove small airborne particles, repairing supply and exhaust fans where needed, and equipping all custodial engineers with carbon dioxide monitors. The education department recently amended its parent-facing ventilation portal, adding the total number of rooms in each school lacking mechanical ventilation, after Chalkbeat raised questions about the accessibility of its publicly available information.

Overwhelmingly, city data shows classrooms have working ventilation whether through HVAC systems or windows: Nearly all of the city’s 56,000 classrooms are currently classified as “operational” or under repair, according to Chalkbeat’s analysis of education department data as of Aug. 20. Only 177 classrooms are listed in the data as having “no mechanical ventilation,” which means they have not been cleared for occupancy. Education department officials, however, disputed the data, claiming that only 35 rooms are presently off limits, and said they are aiming to fix those rooms by Sept. 13.

The city’s improvements in ventilation and its public-facing portal have been heralded by experts. Some skeptics, however, remain concerned that the publicly available data remains difficult to parse and leaves out crucial information as to whether a room’s ventilation is sufficiently turning over enough air. A report from the Harvard School of Public Health recommends four to five air exchanges per hour for “good” ventilation and six air exchanges for “ideal” air flow. The city’s portal simply says if a room has working ventilation without any indication of how well it is working.

“My issue now and moving forward is, do we have accountability from the Division of School Facilities? From the DOE?” said Dermott Myrie, who teaches at M.S. 391 in the Bronx and is a part of MORE, a caucus within the teachers union that focuses on social justice issues. Myrie added that he wanted transparent information on air exchange rates and carbon dioxide levels. “Parents should be able to see when the air quality was tested,” he said. “It should not be controversial.”

Based on Chalkbeat’s analysis of publicly available ventilation data and conversations with air quality experts, here’s what we know – and still don’t know – about air quality in NYC schools:

The education department says it posts classroom-level ventilation status updates in real time.

The education department’s classroom ventilation status reports provide information on individual rooms across the city. The data details which rooms are operational, which are under repair and which lack mechanical ventilation. But these designations are not clear cut. Rooms under repair can still be operational, education department officials said. Further muddying the designations, classrooms do not need mechanical ventilation to be considered operational.

If more than 50% of windows in a classroom can open and the room has two air purifiers, it is declared operational, according to education department standards.

Reports also contain outdated information, even though officials emphasize that they are updated in real time.

The report for P.S. 42, where O’Neill works, states that nearly all the windows in the building are either inoperable or not designed to open. O’Neill confirmed that windows were previously nailed shut or difficult to open, but have been fixed.

“That [publicly available] Excel spreadsheet really needs to go because nobody will understand that,” O’Neill said about the outdated information.

But the data can be a useful advocacy tool. At Urban Assembly Maker Academy, a group of families who called themselves Parents for 100% Safety pushed the education department to improve ventilation before reopening last September. Parents were repeatedly told that their building, the fortress-like six-story Murry Bergtraum campus in Lower Manhattan, was adequately ventilated, but industrial hygienists who examined the department’s ventilation reports said otherwise, multiple parents at the school said. More than two-thirds of the rooms in that building lack windows, according to department data.

After months of activism — and enlisting support from Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and City Council members — the education department said fixes were needed.

By the time the parents participated in a walk-through of the school this past spring, the education department had made a number of changes. With those safety measures in place, the parents seem comfortable sending their kids back to school this fall. Still, they remain frustrated that it took months of activism to get necessary upgrades.

“It’s unsettling to say the least,” Tracey Scronic, a parent at the school, said of the education department’s initial claims that everything was OK.

Most classrooms are ‘operational’ by education department standards.

The education department defines “operational” as having functional ventilation according to the building’s original code. This standard is not based on the air quality scientists recommend to curb COVID. Instead, it is the baseline ventilation required for school buildings to be up to code, said Senior Director of the Division of School Facilities Joe Lazarus.

“At this moment, there’s no COVID ventilation, there’s just ventilation,” Lazarus said during a District 15 Community Education Council meeting in June. He said his team’s objective this past year has been to get schools “back to their original design.”

In other words, the goal was simply to give classrooms the ventilation they were supposed to have when they were built.

Building codes vary according to the age of the structure, so there is not a uniform standard for ventilation. Newer buildings typically require working mechanical ventilation, which can include HVAC systems and supply and exhaust fans. Some older buildings like P.S. 42 rely on windows, which in recent years have not been fully functional according to reports as well as the city’s teachers union.

“Progressively, over the years [the windows] have gotten worse,” O’Neill said about her school. “They wouldn’t close. You’d have to use your imagination and your know-how to try and make sure they stayed where they are supposed to be.”

Is ‘operational’ sufficient for COVID?

To some ventilation experts, the education department’s standards for adequate ventilation are not stringent or specific enough. More than 5,000 classrooms rely solely on one or more windows for ventilation, Chalkbeat found. More than 8,000 classrooms rely on one or more windows and an exhaust fan. In these cases, air flow may or may not be sufficient, experts said. The amount of air flow from a window is largely dependent on weather conditions.

Although the education department’s definition of “adequate ventilation” does not require COVID-specific measures, the department has taken steps to provide an extra layer of ventilation.

By the time schools reopen on Sept. 13, every classroom will have two air purifiers.

The devices provide a maximum of 150 cubic feet per minute of airflow when on their highest setting, according to the company website. Having two of these purifiers on the highest setting would create roughly two air exchanges per hour, though that number can vary depending on the size of the classroom. A recent independent test of the product found it is among the least efficient air purifiers out of a dozen tested. It ranked ninth in terms of its clean air delivery rate, which measures how often the purifier turns air over in a room.

That amount of air exchange could be sufficient, said Dr. William P. Bahnfleth, a professor and the chair of the Epidemic Task Force at The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, which has issued ventilation guidance for schools that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has adopted.

“But it bothers me that [the education department] doesn’t seem to have any kind of target,” he added. “I would have thought that somebody would run some simple numbers to be able to explain what they are doing.”

Custodial engineers have carbon dioxide meters. But they might not be using them regularly.

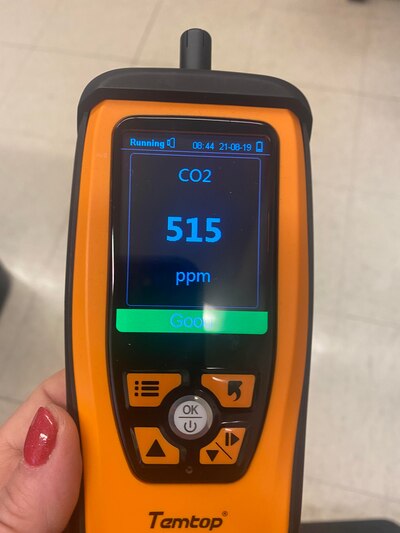

All custodial engineers have been equipped with handheld carbon dioxide monitors that quickly estimate the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Carbon dioxide is emitted when people exhale, so levels of the gas naturally rise as the number of occupants in a room increases. Along with carbon dioxide, people also exhale tiny aerosol particles that can carry the virus. Because there is no easy way to measure aerosol levels, checking carbon dioxide levels can be a proxy for aerosol particles.

Typically, when carbon dioxide levels rise, aerosol levels rise, increasing the risk of COVID transmission if a person infected with the virus is in the room. Outdoor carbon dioxide levels are generally around 450 parts per million (ppm). An indoor space with good ventilation has around 450 ppm to 1,000 ppm of carbon dioxide, according to experts.

Although custodial engineers have carbon dioxide monitors, they have only been instructed to use them at a principal’s request, multiple custodial engineers said.

O’Neill said her team checks carbon dioxide levels every morning in occupied classrooms. The levels have always been within an acceptable range, but she continues to check for “peace of mind.”

“I do it because I’m in an older building and I don’t have the HVAC,” she said.

Two miles away at P.S. 276, which occupies a newer building in Battery Park that is equipped with an HVAC system, custodial engineer Theresa DeChristi said she only occasionally checks carbon dioxide levels.

Regardless of whether carbon dioxide levels are checked or not, the measurements are not available for public viewing. Some teachers and parents have said they’d like to see a dashboard where they can check the carbon dioxide levels in students’ classrooms.

“The CO2 monitor is a tool for public transparency,” said Alex Huffman, a professor in the chemistry and biochemistry department at the University of Denver, who suggested schools set it up in one classroom at a time for three days to see how the numbers change. He also offered ideas on how it could be used in classroom experiments, looking at the spike and then drop of carbon dioxide from dry ice to help understand a room’s air exchange rate.

We do not know the air exchange rate in each classroom.

The air exchange rate, or how many times air turns over in a room each hour, is not available in the education department’s ventilation reports.

A spokesperson for the education department said all custodial engineers are supplied with anemometers, which measure air flow, but at least one custodial engineer said she had not received one. Education department officials did not state whether air exchange rates would be regularly calculated or whether they will be shared with the public.

The air exchange rate can be calculated by taking the volumetric flow of air (measured through an anemometer) and dividing it by the volume of the classroom. If all custodial engineers have anemometers, finding the air exchange rate in each room should not be complicated, experts said.

“You’ve got to know the number of air exchanges in each room,” said Monona Rossol, an industrial ventilation expert who has consulted on the planning of over 80 buildings, “and that’s just a simple measurement.”

Amy Zimmer contributed.