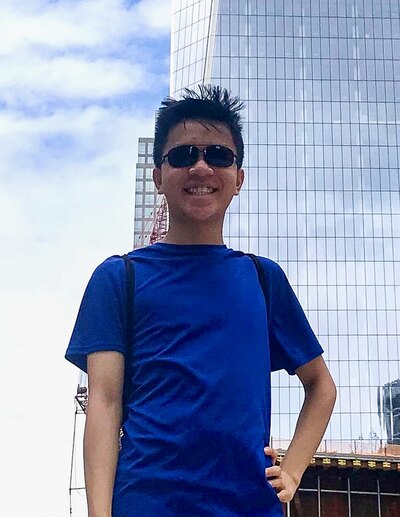

It’s not just the delta variant that makes Zhenghao Lin, a Chinese immigrant, nervous about returning to school next month.

Zhenghao, a rising senior at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School in Brooklyn, said he has been subjected to racist comments at school since he arrived in New York City as a fourth grader. His anxiousness about interacting with non-Asian peers only grew over the course of the pandemic.

“After what I’ve seen on social media and about the Asian American hate crimes in New York City, I do not feel safe going back to school physically,” Zhenghao said. “I may have to deal with the occasional bat-eater comment or, ‘You guys started it’ comment, or any of those microaggressions. If I go on the bus or take the subway, I might have to deal with those comments, too.”

After a rise in hate crimes against Asians in the spring, advocates have heard similar concerns from Asian American families and students about commuting from afar to school and what they may have to endure inside of the classroom when school buildings reopen Sept. 13. For some students, that anxious feeling is compounded by years of microaggressions — subtle, intentional or unintentional actions or statements about a marginalized group — or racist comments they’ve experienced in and outside of school.

In New York City this year, confirmed hate crimes against Asians jumped from four cases in February to 34 the following month, with just over half of those involving assault charges, according to the New York Police Department. The number of incidents has declined since the spring but remains higher than the same period last year.

Cases first spiked the same month when six women of Asian descent were killed in Atlanta, which cast a new spotlight on violence and racism against Asian Americans across the nation. Some violent crimes in New York City were caught on video and circulated on social media, heightening fear among members of the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

Kaveri Sengupta, education policy coordinator with Coalition for Asian American Children and Families, or CACF, said families have shared fears that range from potential hate crimes to microaggressions at school, adding to the nervousness of returning to in-person school for the first time in 18 months.

Sengupta’s coalition has heard from students in high-performing schools with large Asian-American populations who say that their administrators don’t really talk to students about their mental health needs. That can perpetuate the “model minority” myth — that all Asian Americans are high achievers — and ignores these students’ diverse needs that reach beyond academics, she said.

“That whole thing is swept under the rug because the outcomes are good, but what is that actually doing for students’ sense of self, confidence, all of those things?” Sengupta said.

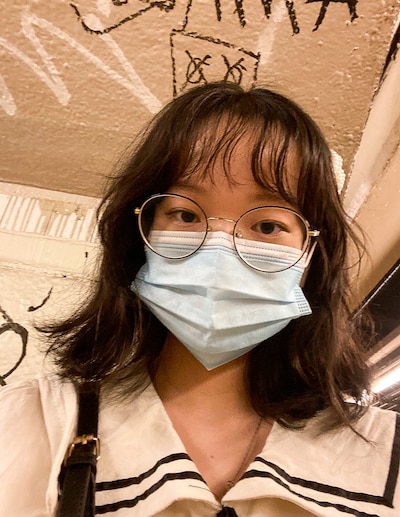

Karen Zhang, 17, decided to stick with remote learning last school year largely because she and her family were worried about her picking up the virus on her 90-minute commute from her Flushing home.

Learning from home became taxing on Karen’s concentration, so she considered returning to Stuyvesant in the spring, when the city offered students another chance to opt into in-person learning. But that’s right when hate crimes were rising against Asian Americans in New York and gaining a resurgence of media attention. Even if her dad dropped her off on his way to work, she would have to wait for an hour outside of the school before the doors opened.

“I decided not to go because it didn’t feel safe physically, but also in terms of health, as well,” Karen said.

Karen said she’s never been physically harmed because of her race but has dealt with many microaggressions, especially in middle school on the Upper West Side, where the Asian student population was small. She recalls her peers making faces when they smelled the dumplings she would eat for lunch. Classmates would ask her to do origami for them even though she didn’t know how. She didn’t realize she was being stereotyped until recently. One of the best things schools could do to make nervous students feel better is to prioritize education about what anti-Asian harassment and microaggressions look like, Karen said.

“Education is a huge, huge, huge thing when it comes to addressing anti-Asian violence,” she said. “A lot of the hate crimes happened because people don’t see Asian Americans as Americans — just seen as a perpetual foreigner.”

When he first moved to the United States, Zhenghao said he would make fun of himself in order to make others laugh and earn their acceptance, but sometimes in response his peers called him a “dumb Asian.” His freshman year of high school, some students in his gym class would block Zhenghao and his Asian friends from serving when they played volleyball. They were often cut in line at lunch, and once, a student barred Zhenghao from entering the boys locker room, saying, “Look at this Chinese n - - - -,” referring to a slur for Black people.

In the weeks before schools closed, Zhenghao and his friends were exiting the locker room when another student said, “Holy crap they all look the same.” He wasn’t sure if that was directed at his group, but “there were indeed a lot of Chinese-looking people out in the locker room,” Zhenghao said.

Zhenghao chose a fully remote schedule last school year in part because of virus concerns, but also because he continued to see anti-Asian posts on social media, such as Instagram. Those posts, coupled with the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes in the spring, made him question his identity.

“I was very depressed because I was like, why did I have to be born as a Chinese person? Why can’t I be like someone else, like a Latinx American or a white American, because like, people would say things about me just because of something I didn’t choose, which was being Chinese,” he said.

Now faced with a full return to school next month for the first time since March 2020, Zhenghao doesn’t know what would ease his nerves, though he has sought out therapy. His fear of commuting has dampened as he’s taken more trains and buses to and from his downtown Brooklyn apartment — but he does recall a man on a train moving to a seat far away from Zhenghao and his mother as they walked in.

When videos circulated of Asian people getting beaten up on the subway, 17-year-old Jenny Liu’s parents became even more apprehensive about her leaving their apartment in Ocean Hill.

Jenny, who is Chinese American, didn’t realize it right away, but she noticed that she wouldn’t look at her phone or read a book while taking a train this summer to her research internship and volleyball practice. Jenny is often the only Asian person in her train car for nine to 10 stops. She hasn’t experienced any violence on public transit before, but she’s felt uncomfortable: Two separate times, a fellow passenger got up and moved away from her as she took a seat nearby.

Taking the subway this summer has helped to ease her nerves for the commute this fall to Stuyvesant High School in lower Manhattan. After learning remotely since March 2020, Jenny is looking forward to seeing her friends, playing volleyball, and having a more normal senior year.

“That familiarity with taking the train more — still wearing the mask, of course — is a good thing, and that’s preparing me going back to the school year,” Jenny said.

Dina Yang, a 17-year-old rising senior at School of the Future in Chinatown, was with a group of her Asian American friends at lunchtime right before schools closed last year, when a student walked past and said, “I hope you don’t have COVID,” while laughing. Just before masks were required on public transit, Dina was boarding a subway train when a woman standing near the door pulled her shirt over her face. Around February, a man pulled down his mask and yelled “China” at Dina and her mother as they walked through Koreatown.

Virus concerns kept Dina, who lives in the Bronx, learning exclusively from home last school year, but her family felt more confident in that decision when they saw reports of rising anti-Asian hate crimes in the spring. She typically travels about 50 minutes to school, and her family considered it a risk for her to travel on her own.

But like some of her peers, Dina is feeling more comfortable with the idea of commuting after using the train this summer to get to work about an hour away without incident, she said.

“I realized nothing really happened to me this summer,” she said. “But it’s still on my mind that it would be a possibility.”

In a statement, education department spokesperson Nathaniel Styer said schools play a key role “in educating students about how the diversity of our differences makes us stronger,” and the department works with teachers and school safety officers “to make sure students are physically and emotionally safe during this time.”

In response to the spike in hate crimes, the school safety division identified schools with predominantly Asian American and Pacific Islander students and created “safe corridors,” where police presence is increased between transportation hubs, such as subway stops, and the school. Those will be in place beginning the first day of school.

On top of normal requirements for reporting bullying, the education department created an online portal where parents can file bullying complaints.

Sengupta, with CACF, said her organization wants more data on how many bilingual counselors exist in city schools and what languages they speak, noting that sometimes students feel most comfortable approaching someone for help when that person looks like them or speaks their native language. The education department is planning to hire a full-time social worker for every school building without one or without access to a school-based mental health clinic. But Sengupta wants schools to be more intentional about who they hire.

The organization also wants the education department to conduct targeted outreach to families that alerts them about signs of potential mental health problems so that they know when and where to go for help for their children. For many Asian American families, mental health support can be considered a “western solution, in some ways, to a western problem,” Sengupta said.

The end goal is to ensure that this year “every student, every family” has a “trusted adult in the school building” who they can talk to about things beyond academics, Sengupta said.

Dina, the student from School of the Future, said she often felt mentally drained by remote learning, but teachers never reached out to check on her. She felt that was because she gets good grades. Her advice to teachers: “Check in on your students, often.”

Amanda Chen, a rising senior at School of the Future and a classmate of Dina’s, experienced a rash of anti-Asian, coronavirus-related harassment at school right before the pandemic shuttered buildings. Chen, who lives in Chinatown, is more concerned about encountering racism in school than other public places, since she’s used the train often this summer, but she feels more comfortable knowing she has supportive adults at school.

“If the racism happens at school and it’s targeted against me, I would feel more comfortable reaching out to the authority, the principal or the teachers who I feel comfortable talking with,” Amanda said.