A school funding task force has released preliminary proposals that could reshape spending at virtually every New York City public school, from those that serve large numbers of low-income students to the city’s most selective high schools.

Multiple proposals would disproportionately benefit the city’s growing number of small schools or campuses with an outsized share of students living in poverty. Others — such as charging schools the same amount of money per teacher regardless of their actual salary — could funnel resources away from schools in some of the city’s neediest neighborhoods, education department projections show.

Some ideas address long-standing controversies, such as eliminating an extra pool of money that flows to some of the city’s most competitive high schools, including Stuyvesant and Bronx Science. But other proposals are likely to spark new debates, including a proposal to eliminate a funding boost for career and technical programs and alternative schools that serve students who are behind in credits and at risk of dropping out.

Each of the proposals would alter the city’s “Fair Student Funding” formula, which represents roughly two-thirds of school budgets. The formula sends schools a baseline amount of money for each student — this year, it’s about $4,197. But certain student groups come with additional dollars, including those with disabilities, English language learners, and students with low test scores.

For years, experts and advocates have debated whether the formula — which is generally meant to send more money to schools with higher-need students — is as fair as its name suggests. In an unusual rebuke, the city’s Panel for Educational Policy voted not to approve the funding formula last April, but later reversed course after city officials promised to set up a task force to propose changes that could be incorporated in time to impact school budgets next year.

It remains to be seen how much force the recommendations will have, as a similar task force issued suggestions that were ultimately shelved. The latest task force’s final recommendations are due by the end of the month, and the decision about whether to enact them will rest with schools Chancellor David Banks and Mayor Eric Adams. Some members aren’t sure if their ideas will be paid for with new money or if they must come at the expense of other funding priorities.

“We’ve had six or seven sessions so far and they’ve been really good and productive,” said Dia Bryant, a co-chair of the funding task force and executive director of Education Trust New York, an advocacy group. “We hope that [Banks] takes those recommendations into serious consideration.”

Here are six things to know about the recommendations the task force is considering:

New funding for high-need students — and schools

Nearly one in 10 New York City students is homeless — representing over 100,000 students — and advocates have long called for the city to dedicate more funding to those students.

One of the working group’s proposals would do just that: adding between $43 million and $86 million in funding, which would boost per-student spending for students living in temporary housing, education department figures show. Principals have wide discretion in using the money that flows through the Fair Student Funding formula and a funding boost could support additional staff, expanded attendance outreach, and more.

A separate proposal would increase funding at roughly 500 high-need schools rather than solely giving a boost for individual students in a specific high-need category. Schools with large shares of homeless students, those living in poverty or foster care, or schools that enroll high proportions of students with disabilities or English learners would receive additional money.

“It’s good they’re taking a look at these things,” said Michael Rebell, executive director of the Center for Educational Equity at Columbia University. He added the lack of additional funding for homeless students is “something that should have been corrected a long time ago.”

Eliminating a special bonus for elite high schools

The city’s funding formula is generally designed to give schools that enroll high-need students more money. But the formula also offers additional resources for certain selective high schools — including the city’s eight specialized schools, which admit students based on a single exam. The working group is considering a proposal to end that funding bump.

This year, several selective schools are set to receive about $1,049 more per student than they would otherwise, which costs about $20.5 million, city documents show. (A handful of non-specialized schools also receive the bonus; city officials have not explained why or what criteria are used to give schools the extra money.)

The education department argues those schools need extra funding because their academic programs are more expensive to run, going above and beyond traditional schools. Critics have long contended additional funding for the small group of selective schools is inequitable, especially as many of them enroll relatively few Black and Latino students, students with disabilities or those learning English.

Reducing funding for career education and alternative high schools

That same proposal, however, would also eliminate extra money given to career and technical programs in addition to transfer schools, which serve students who are overage and at risk of dropping out — a possibility that raised some eyebrows during a public input session on Tuesday. (Those programs will receive about $32 million in additional funding this year.)

“I can imagine that transfer schools require a lot of funding based on the fact that these are students who are coming from other schools and coming from difficult situations,” said one principal who attended the meeting.

Sheree Gibson, a member of the funding task force who fielded questions, didn’t say why the group is considering a recommendation to cut funding from transfer schools or career and technical programs, but emphasized the recommendations are not final.

Charging schools the same amount per teacher

Teacher salaries come directly out of school budgets — and more experienced teachers command higher salaries under the teachers union contract.

One proposal would change that so schools pay the same amount of money per teacher regardless of the actual salaries of the educators in a given building, freeing up about $175 million in additional funding at schools with more experienced teachers.

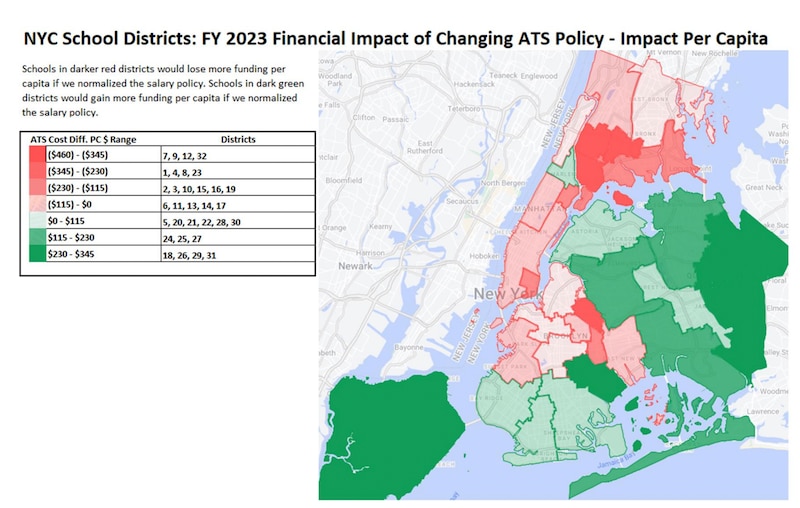

But in the absence of a significant infusion of new money, charging all schools the same amount per teacher would essentially represent a transfer of resources from high-poverty schools to lower-poverty ones since high-poverty schools generally employ less experienced teachers, education department projections show.

The policy change would reduce funding most in the South Bronx, central Brooklyn, and the Lower East Side, while increasing it most on Staten Island and certain stretches of Queens.

Still, the policy change has some supporters, including the city’s teachers union, which is represented on the task force.

“Schools have to be able to hire and keep the educators their students need, whether that’s to meet special education requirements, the needs of multi-language learners, CTE or other necessary programs,” Alison Gendar, a United Federation of Teachers spokesperson, said in a statement. “The current formula incentivizes poor hiring decisions.”

Increase base funding for schools

In addition to per-student funding, every school receives $225,000 — generally meant to pay for a principal and a secretary. But the task force is considering whether that number should be higher to include money for a social worker, assistant principal, and guidance counselor.

The cost of those additional positions would be $527 million, department projections show, and would require moving funding from about 500 larger schools to 1,000 smaller ones.

Questions remain about how to pay for changes

Several of the draft proposals would require millions of dollars in new funding or reductions elsewhere in the education department’s budget.

For instance, the city’s modeling shows that adding new funding for homeless students could be paid for by cutting money for students who are below grade level and reducing a per-student funding bump that typically accrues when students reach middle or high school.

Public meeting minutes show some of the working group members have repeatedly shared “concern[s] about looking at new models within a fixed pie, rather than with new funding.” And new funding may be hard to come by, especially as Mayor Adams has called on city agencies, including the education department, to reduce spending.

“I think the work group has been vocal about getting away from this zero-sum game and I think that is one of the major tensions,” said Bryant, the co-chair of the funding task force.

An education department spokesperson did not say if the city might allocate new funding without cuts to other parts of the formula. Officials said the proposals will be reviewed by the chancellor and there will be opportunities for feedback by parent councils this winter.

“We deeply appreciate the work of the Fair Student Funding Working group, and look forward to reviewing any and all changes suggested to enhance equity in the formula,” education department spokesperson Jenna Lyle wrote in a statement.

Additional materials and updates about the working group are available on the education department’s website.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.