Over the first 16 years of my education career, I grew increasingly alarmed over gaps in students’ reading skills.

But I was the social studies teacher. What was I supposed to do to help struggling readers other than modify lessons and curriculum? My efforts barely scratched the surface.

For years, this was the status quo in my classroom, like so many others across New York City. I did my best to help struggling readers and tried — like countless teachers, administrators, and politicians — to ignore the crisis facing every single student who does not learn to read. Just under half of students in the city passed state reading exams for grades 3-8 last year.

Once, when I had a student who couldn’t read at all and struggled even to recognize letters, administrators reminded me that I was not a literacy teacher. My job was to figure out how to teach the content.

I was shocked to my senses in 2014 when I was tapped to work as an educator in a program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that seeks to foster critical thinking skills through higher-level questioning about art.

My students exceeded all expectations in their ability to think and analyze, but many of the same kids struggled with reading. I couldn’t make sense of it. Certainly, kids with this level of intelligence should be able to read.

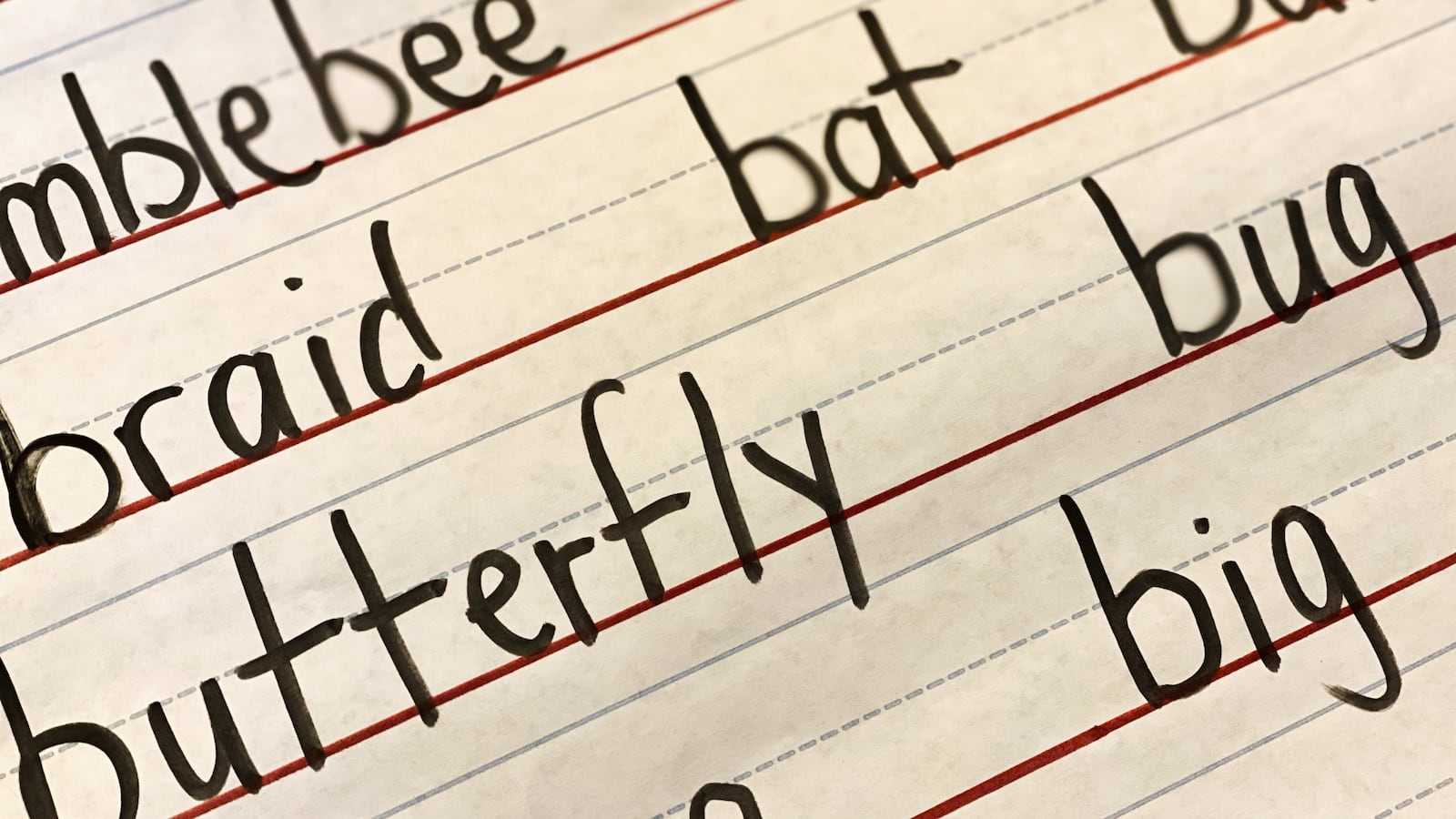

Unable to bear the thought of their potential being thwarted by literacy challenges, I decided to find out what more I could do to help. I enrolled in an associate-level course with a fellow of the Academy of Orton-Gillingham, a nonprofit that certifies teachers in an individualized and multi-sensory approach to teaching reading through phonics.

Learning to identify the signs of dyslexia, in particular, came as another shock. As I thought back to the struggling readers I’d had in my classroom over the years, I came to believe that I’d been working with a steady stream of students with unidentified dyslexia.

The school system’s failure to identify these students guaranteed that they didn’t receive the help they needed to become functional readers — typically, this is instruction that emphasizes the connections between letters and sounds.

I struggled with feelings of guilt. Should I have known better? Could I have done more?

I soon realized that subject-area teachers like me weren’t trained to identify and help struggling readers. Even if we had identified students with print-based learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, there was often no place to send them to get the support they needed.

Dyslexia is a common source of reading difficulties — 10% to 20% of the overall population is thought to have symptoms — and remediation best practices are well established. Despite this, shockingly few teachers and administrators in New York City understand the signs of dyslexia.

As a result, we are leaving too many behind: The kids who teachers say are nice but not good at reading. The kids in the dean’s office who choose trouble over facing another page they can’t decipher. The kids who get the gist but always seem to miss something.

Some schools have implemented small-scale remediation programs, with varying rates of success. Some, like mine, have a few individuals doing their best to help struggling readers in groups that are too large during meetings that are too short.

I continue to teach social studies, but I also provide students with instruction through the Orton-Gillingham approach as part of my school’s academic intervention service. A colleague has recently begun her training, adding to the capacity for this work at my school. We are also trying to provide our colleagues with literacy strategies in their content areas, such as access to text with audio and vocabulary instruction that analyzes etymology, or word origin.

We are doing our best to help students, but we clearly need change on a larger scale. The change needs to be done with fidelity. Teachers need adequate training to identify those with dyslexia. Students need access to diagnostic testing and to the research-based methods shown to be most effective in teaching students with dyslexia.

Unfortunately, the city’s efforts to address reading disorders have largely helped well-to-do families. The New York City Department of Education spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year to send kids with learning disabilities — many of them dyslexic — to private school. But families who can’t afford pricey private neuropsychological evaluations often struggle to access that service.

Mayor Eric Adams has taken initial steps to make dyslexia screening tools available to every teacher in the city; those changes haven’t yet trickled down to my school. Even so, Adams was asked to host the World Dyslexia Assembly in New York City this spring.

Meanwhile, state lawmakers passed a bill earlier this year that would boost dyslexia screening, curriculum, and teacher training. Gov. Kathy Hochul should sign the bill, and I hope state leaders will push the Adams administration to do more.

Until every struggling reader in the city gets the help they need, those of us who have opened our eyes to the causes of this literacy crisis will continue to reach as many kids as we can, knowing that many more are slipping through the cracks.

Christine Sugrue is a middle school social studies teacher in the New York City public schools and an associate member of the Academy of Orton-Gillingham.