Facing a mounting crisis of delayed payments that have left some preschool providers hurtling toward insolvency, top education department officials vowed on Thursday to clear the backlog and pay providers on time.

In the next two weeks, officials said they are spinning up “rapid response” teams to individually work with the community organizations that operate the bulk of the city’s free preschool programs.

The goal is to swiftly clear $140 million in back payments to providers from the fiscal year that ended in June. All but $20 million of that money is connected to some 4,000 invoices that have not been submitted, officials said. The teams will meet with providers on site or virtually, a move that schools Chancellor David Banks said would help create a clear line of help.

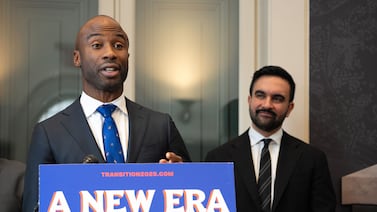

“Underlying these challenges is a lack of infrastructure here at the DOE that failed to even give the providers the support that they needed,” Banks said at a press conference. Officials vowed to process invoices within 30 days of receiving them going forward. An education department spokesperson did not provide a total figure for outstanding payments to date.

Officials also promised to pay community organizations 75% of last year’s contracts for early childhood programs regardless of how many students showed up, an effort to protect them against lower-than-expected enrollment.

Banks framed that as a new promise that would help keep early childhood programs afloat. But current and former education department staffers with knowledge of the early childhood payment process said it wasn’t clear how different that is from the current contract with providers, which includes similar payment guarantees.

“We already do this and it was being passed off as a new policy,” said an education department staff member who works in the early childhood division and spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. An education department spokesperson said the 75% minimum was previously dependent on documented expenses and enrollment, which will no longer be conditions for receiving the money.

Thursday’s announcement comes at a precarious moment for early childhood education providers, a sprawling network of city-contracted nonprofits that were key to former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s expansion of free prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds. Although payment problems have bubbled up in the past, they appear to have intensified this year.

Banks blamed the previous administration for problems with the payment system and argued de Blasio was committed to creating thousands of pre-K seats, particularly for 3-year-olds, without enough regard for demand — leaving some providers competing with each other for too few children.

“That increase was not based on any logical analysis of what our communities actually need,” Banks said. Department officials said they are deploying consultants to study the payment system and figure out where seats are needed or should be scaled back.

Josh Wallack, who oversaw the expansion of pre-K in the de Blasio administration, previously said that a new wave of contract renewals and a requirement for monthly invoices to capture real-time enrollment, could have contributed to some payment glitches.

Still, “The new team has had almost 10 months to address that,” he wrote on Twitter last month. “The payment systems worked for years. We certainly had issues in a system with hundreds of contracts, but nothing remotely close to this.”

One former early childhood staffer pointed to a wave of departures and the sidelining of several key officials in the education department’s early childhood division early in the new administration as a source of the payment delays.

“The talent that they hemorrhaged in the first months was outrageous,” said the former staffer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “You lost specific people … who were the ones who could get in there and fix problems in the system.”

Whatever the cause of the delays, providers are struggling. Sheltering Arms, which serves about 400 children, has already announced plans to close, the New York Post first reported. Others have resorted to taking out loans or have simply not paid their own employees on time, said Gregory Brender, the chief policy and innovation officer at the Day Care Council of New York, which represents city-contracted child care providers.

Still, Brender said he is optimistic that the rapid response teams will help clear the backlog of payments. “I think this is a significant improvement and it addresses an immediate crisis that is destabilizing the system,” he said. “It’s just been a challenge for a lot of providers to figure out who is the right person to deal with.”

An education department staffer who works in the early childhood division said it could be difficult to provide intensive support for providers, as the department has struggled with an exodus of staff, low morale, and leadership turnover — including the abrupt resignation last month of a senior official responsible for overseeing payments to providers.

“Doing one-on-one engagement might be what’s necessary here, but with our drastically scaled back headcount, that’s hard,” the staffer said. City officials said they have already assembled the response team, which will include 20-25 people.

The division of early childhood education is facing other headwinds, too. The city’s teachers union is holding a vote of no confidence against Kara Ahmed, the deputy chancellor who oversees early childhood education — on the heels of a staff reorganization in that department.

Education officials previously announced plans to reassign about 400 early childhood workers, including instructional coordinators and social workers. Banks argued the move was intended to place central staff members closer to schools, but most of them already worked inside preschool classrooms and some expressed confusion about the purpose of the reorganization.

“We’re going to programs saying, ‘I got excess notices, but I’m still here because I want to do my job but I don’t know if I’ll be back tomorrow,’” said one instructional coordinator who spoke on condition of anonymity, and who submitted a vote of no confidence against Ahmed. (When staff are excessed they lose their current positions but still get paid and may apply to other positions in the department.)

For his part, Banks fiercely defended Ahmed on Thursday and said he was deeply disappointed by the no confidence vote. “The frustration is, ‘We don’t want to be close to kids,’” Banks said of those opposed to the department’s reorganization.

“For those who have decided to do a vote of no confidence,” Banks added, “you should ask them very pointedly: What does that mean when you’re not losing your job?”

Michael Elsen-Rooney contributed.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.