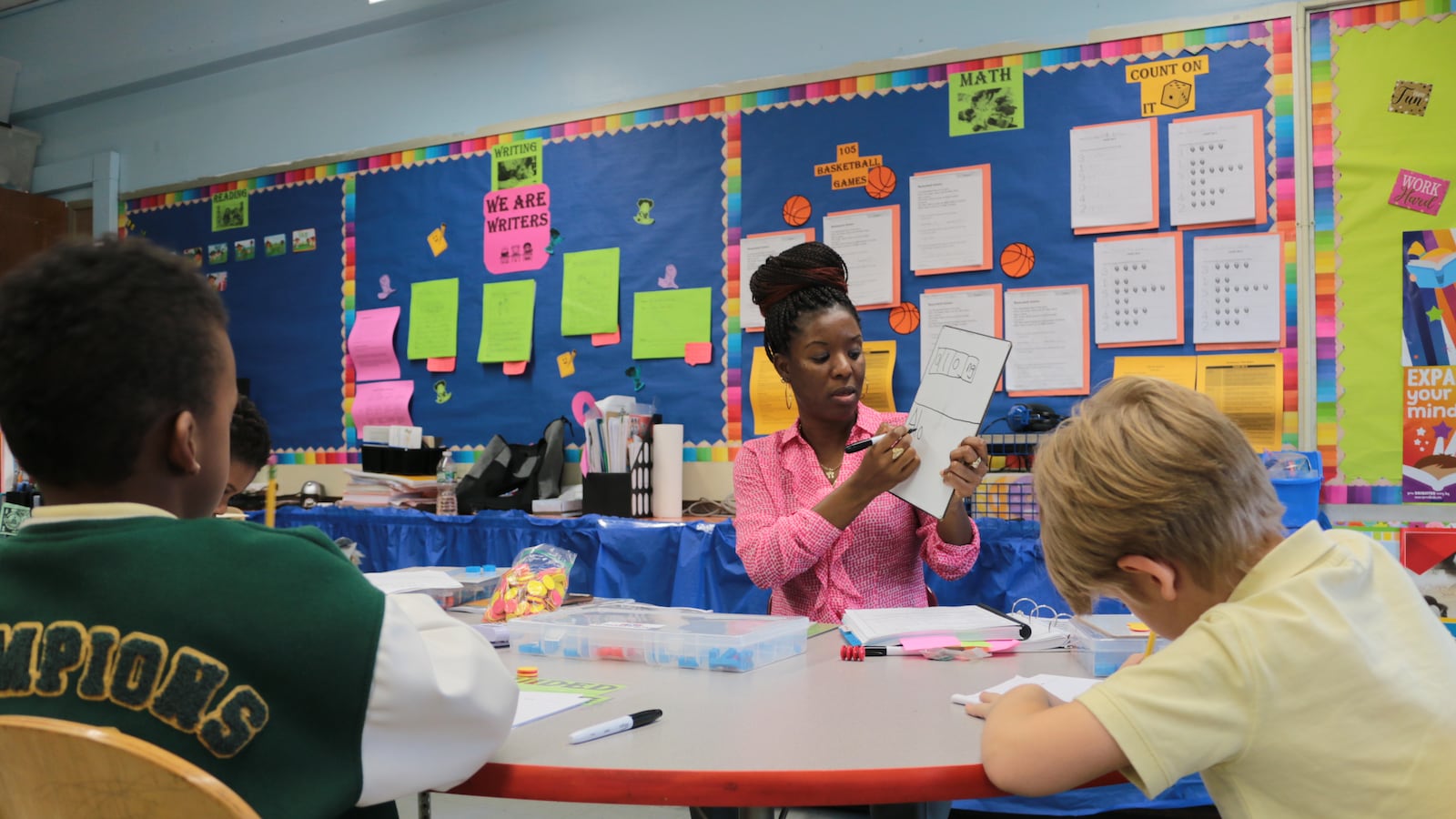

Just after the school day winds down, a group of three students at Brooklyn’s P.S. 40 sit in a semicircle and crack open “Looking for Lunch,” an illustrated book with large print. With help from a tutor, they begin reading aloud in unison, running their fingers along words like “hungry” and “animals” as they go.

Next door, a student is working with a one-on-one tutor and struggling with a more basic task: forming the word “tan” using small wooden blocks to represent individual sounds. He’s just beginning to grasp the relationships between sounds and letters.

In both classrooms, these first graders are behind their peers and at risk of joining the roughly 50% of city students who are not proficient readers by the time they reach third grade. To help catch them up, P.S. 40 is leaning on an intensive strategy: individualized tutoring at least three times a week.

The program pairs CUNY students studying education with New York City public school children who are struggling to master literacy skills. Known as the CUNY Reading Corps, the effort has grown into one of the largest tutoring initiatives involving pre-service teachers. This year, it’s projected to include more than 800 tutors and reach roughly 2,700 of the city’s public school children, primarily first and second graders.

Researchers have pointed to high-dosage tutoring as a tried-and-true method of reaching students who are struggling or were derailed by the pandemic. Catching up students who are behind — but still at widely varying skill levels — is a significant challenge in a typical classroom with dozens of students. Tutoring in small groups or one-on-one is one way of making that task more manageable, though it can be expensive and challenging to pull off on a large scale.

The Reading Corps program, launched in fall 2020, has helped ease some of those barriers. The idea came from Katie Pace Miles, a Brooklyn College professor and literacy expert who had two main concerns. For one, hands-on teaching opportunities for her education students were upended.

She also worried that more affluent families were able to marshal their own resources, launching learning pods or hiring tutors, creating even larger opportunity gaps compared with thousands of low-income children, many of whom struggled to access remote learning.

“Some children maintained, or gained, or accelerated,” Miles said. “And other children were left with shuttered school buildings and hybrid learning that wasn’t really working for them — and no additional support.”

A high-dosage tutoring program shows promise

The Reading Corps program helped address both of those problems, paying tutors in graduate or undergraduate education programs between $20 to $25 an hour to work with public school children for three to five sessions a week over about 13 weeks.

Before they begin working with children, the tutors receive between six and 12 hours of training in one of two reading programs, both of which include phonics lessons. Reading Ready, which Miles developed herself, is designed for students who are furthest behind, training them how to recognize foundational letter-sound relationships, form words by blending different sounds, and read basic sentences. The lessons typically last about 20 to 30 minutes.

The other program, Reading Rescue, is used across the city and is meant for students who can already recognize letters but are still below grade level. During the 30- to 45-minute sessions, children participate in step-by-step phonics lessons, read texts out loud, and respond to questions about what they’re reading. The lessons are typically delivered individually but sometimes include groups of up to three students.

Since the program launched in 2020, it has grown from 275 tutors to more than 800 at a cost of about $2.9 million for this school year and next summer, an effort that is largely foundation funded.

“Schools were very responsive” to the program, Miles said. “This really started out of urgency and need — and we were trying to go big.”

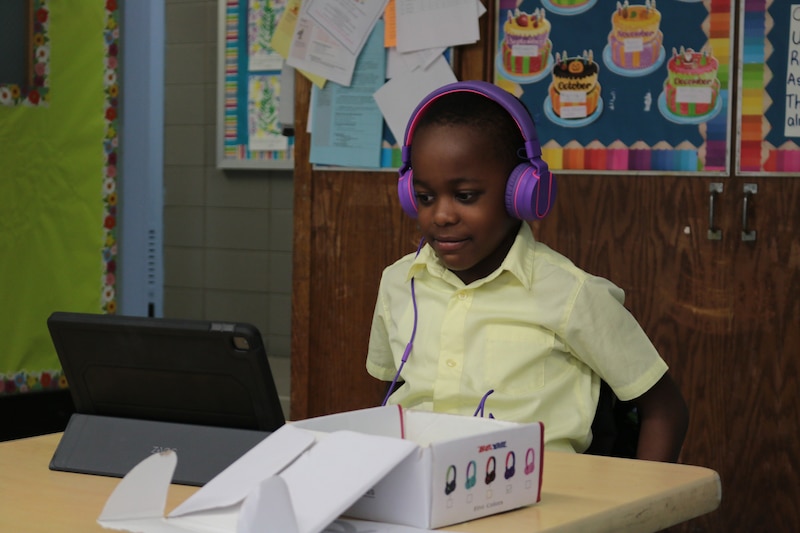

They initially provided lessons remotely, as the program launched when school buildings were still mostly empty. Even though campuses are now open, the majority of students still participate virtually, logging in from school buildings or from their homes outside of regular school hours.

Still, there have been some challenges. Schools aren’t always excited about adding a virtual tutoring program, though Miles said it can be as effective as in-person tutoring. Online sessions also make it easier for tutors to arrive on time and reduce opportunities for viruses to spread. At P.S. 40, the school’s principal pays a teacher to help supervise the students who participate remotely.

Student attendance is not always high, a common stumbling block for tutoring programs. When the Reading Corps first launched, attendance was in the mid 60% range. Last year, attendance was closer to 70% and is now consistently above 70%.

“It takes some students longer to get through the program, just because they’re not always able to make their sessions,” said Erin Croke, CUNY’s director of literacy initiatives. “We really want to get them in and out,” she added, “so that we can then serve more students.”

City officials have said they want more students to receive the kind of systematic reading instruction offered through the Reading Corps program, and are requiring elementary schools to adopt phonics programs approved by the city. But those efforts to improve instruction will likely take time, necessitating remedial strategies in the interim.

“While we spend the time figuring that out, we need to provide students with this service,” Miles said.

CUNY officials say the program is showing signs of effectiveness. However, the tutoring program has not yet been studied rigorously, making it impossible to definitively say how effective it is. Miles said she is in the process of collecting data from student assessments to understand the program’s impact.

Outside experts who are familiar with the research on tutoring said the program is promising and should be studied carefully.

“The CUNY Reading Corps has all the design features that set a tutoring program up to succeed,” said Matthew Kraft, a professor of education and economics at Brown University who called for a national expansion of tutoring to help address learning disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Not all tutoring programs are created equal

At P.S. 40, an elementary school in Bedford-Stuyvesant where more than 90% of students are Black or Latino and 89% come from low-income families, the need for individualized help was clear, Principal Louise Antoine said.

Although challenges with teaching students to read are nothing new, kindergartners have been arriving further behind, unable to identify their letters. Fewer arriving kindergarten students had attended prekindergarten during the pandemic, one reason the principal surmised they were further behind.

“We noticed that a lot of our students are coming in, and they’re not ready to read,” Antoine said.

Antoine previously had mixed experiences with tutoring. The school experimented with a virtual program that students completed from home, but it was costly, the tutors didn’t have much training, and attendance among both students and tutors was spotty. But the Reading Corps program, she said, has been much more effective.

“The tutor has to be invested,” Antoine said. “The tutor has to be trained in how to support children in reading. I learned not every program has those qualities.”

Mary Escobar, an undergraduate student at Hunter College who is tutoring at P.S. 40, said she became interested in teaching literacy skills after helping a child with dyslexia she was babysitting. The CUNY Reading Corps jumped out to her as a chance to receive more formal training and practice in a public school setting.

Even though the Reading Ready lessons she’s delivering are highly regimented, not all of the sessions are a breeze. During a recent afternoon, a student named Kyrie was struggling to focus, squirming in his seat and playfully tossing tiny wooden cubes meant to represent sounds.

After some sessions, “I don’t get that feeling that we actually made progress” Escobar said, “and that’s a tough feeling.” But the goal isn’t just to deliver instruction — it’s also to help her figure out how to adjust and be a more effective teacher once she’s in the classroom full time.

“I’ve wrestled with how important it is to get the kids focused and believing in themselves and getting positive reinforcement for their effort rather than just trying to get something done,” she said. “What I’m doing with these kids is going to help me down the line with so many other kids.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.