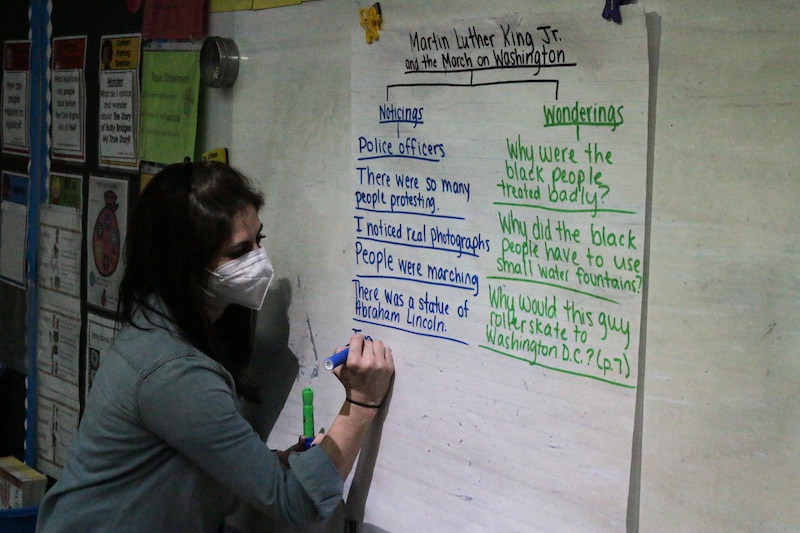

Dominique Filiberti passed out a slim blue book about the 1963 March on Washington, set a timer for two minutes, and told the 18 second graders in front of her to flip through the pages and share their observations.

“I noticed there’s a bunch of people to celebrate,” one student chimed in, zeroing in on illustrations of crowds on the National Mall. Another student, a 7-year-old named Fatima, turned to a photo of two water fountains, one labeled “for colored only.”

“What’s that called when they’re kept separate?” Filiberti asked.

“Separated?” Fatima offered. With a bit of prompting, the entire class thundered a recent vocabulary word in unison: “Segregation!”

The scene unfolding at P.S. 236 might seem like a straightforward history lesson, but it represents a paradigm shift in how educators at the Bronx school are teaching students to read.

The school’s leaders concluded that the reading curriculum they were using — created by Columbia University’s Teachers College and long championed by the city’s education department — wasn’t working for their students, who are predominantly low-income and largely not proficient readers. They decided to ditch the widely used program where students are often encouraged to independently read books of their choice. Instead, even as the pandemic threatened to derail their plans in September 2020, they moved ahead with a transition to a new reading curriculum where students collectively tackle challenging history and science texts.

“We could not wait till we were back to normalcy,” said Lisa Schwartz, a literacy coach assigned to the school.

Newly appointed schools Chancellor David Banks recently offered his own blunt assessment of the Teachers College curriculum: “It has not worked.” But changing how a school teaches reading is more complex than simply buying new materials, and the shift underway at P.S. 236 may offer lessons to other elementary schools in New York City considering a curriculum overhaul.

The stakes are high two years into the pandemic, both for P.S. 236 and students learning to read across the city. Children who struggle with reading and math in elementary school are more likely to struggle academically later on and less likely to graduate.

Before the coronavirus hit, less than half of the city’s students in grades 3-8 were considered proficient readers, according to state tests. The pandemic has only multiplied concerns that students have been knocked off track.

“You’re always going to have diverse learners, but the gaps in those abilities are much more stark,” said Jori Wolfe, who teaches alongside Filiberti in second grade, where students have had each of their school years since kindergarten disrupted by the pandemic.

In the school’s main foyer, a chart of state test scores stretching back a decade underscores the task at hand. Before the pandemic, 37% of students were considered proficient, about 10 points below the city average.

“Our kids weren’t performing, we didn’t have enough proficient readers on the state exams, but we knew our kids were smart and were capable,” said Afrina Talukdar, the school’s principal. The issue, as she increasingly came to see it, “was us.”

One school caught in the reading wars

Little in elementary education is more fundamental than teaching children how to read, and debates about the best approaches are so contentious they’ve earned the moniker the “reading wars.” Talukdar joined P.S. 236 as a teacher 27 years ago and has seen different philosophies of reading instruction, and the accompanying jargon, cycle through the school.

When Talukdar began her career, the dominant approach held that learning to read is an innate process that can be unlocked by exposing students to literature and fostering a love of reading. That model, often referred to as “whole language,” typically doesn’t include much direct instruction on the relationship between sounds and letters, known as phonics.

“It’s the whole idea that kids learn to read naturally instead of explicitly teaching those foundational skills,” Talukdar said. “This is how we were trained to teach literacy. That was the gold standard.”

Critics of that approach argued for more explicit instruction, which led to a compromise called “balanced literacy” which found a middle ground by sprinkling in more phonics and direct teaching of reading skills.

Balanced literacy was pushed into schools across the city in 2003 and embedded deeply at P.S. 236 through a curriculum from Teachers College called Units of Study. In recent years, that approach continued to enjoy support from the department’s leadership.

In a typical class at P.S. 236, educators using the Teachers College curriculum would offer a short mini-lesson on a specific skill, such as how to find a text’s main idea, and then ask students to apply what they learned by reading independently. Students who struggled to read would be directed to choose easier books so they wouldn’t get frustrated and give up. In the earliest grades, students were encouraged to use context clues, such as looking at pictures, to help them interpret the reading, a practice that has come under fierce criticism.

Teachers at the school liked that students had plenty of time to practice reading, but they found it hard to keep track of whether students were applying the skills they learned because each student chose a different book. Sometimes it felt like they were taking students’ word for it that they were understanding the texts in front of them.

“If you’re a grade-level student or above [Teachers College] can work beautifully,” said Wolfe, especially if students were already getting practice at home. “If you’re a student who has struggles or learning issues you’re going to fall through the cracks.”

Overcoming the ‘knowledge gap’

New York City principals have almost complete control of the curriculum, so the task of deciding whether to try a new reading program rested with Talukdar.

A confluence of factors made her reconsider the school’s approach. She attended a series of professional development sessions that opened her eyes to other models. Meanwhile, the Teachers College curriculum faced growing pushback by independent curriculum reviewers and outside academics. (Lucy Calkins, the author of Units of Study, said significant revisions are in the works that are “informed by the science of reading research” and will be released this summer. She declined to comment on Banks’ critique of the curriculum.)

Talukdar was also influenced by a book called “The Knowledge Gap,” which argues that once students can “decode” words by sounding them out, a key to understanding what they’re reading is having lots of background knowledge in subjects like history and science.

“How we taught reading was we taught strategy absent of content,” Talukdar said. “We unpacked it with the staff, and it became a school-wide mission to really think about shifting the curriculum.”

The school began devoting some of its professional development time to sorting through various options, and Talukdar gave teachers a chance to weigh in on the final candidates. The winner: a curriculum called Wit & Wisdom from a company called Great Minds.

Under the new curriculum, lessons revolve around a book that the entire class reads aloud together, rather than hinging on students selecting books to read on their own. Recently, students completed units on the concept of change, such as seasonal shifts, and the American West.

The materials are designed to be culturally responsive and include a range of perspectives, according to the curriculum’s creators. Teachers pepper students with questions about what they’re hearing, emphasizing vocabulary words. They prompt the students to conduct quick “turn-and-talks” with each other, and ask them to write reflections in their journals.

Although there are not many rigorous studies that show a direct link between a content-rich curriculum and better academic outcomes, proponents point to some evidence backing the approach.

Unlike the Teachers College curriculum, which is pitched as a comprehensive approach to reading instruction, Wit & Wisdom is focused more narrowly on building students’ background knowledge and is meant to be paired with other programs that focus on teaching fundamental reading skills.

P.S. 236 uses a program called Fundations, which offers systematic phonics instruction to directly teach students how to decode words. The school offered those phonics lessons even before they switched curriculums, and students continue to receive them for 30 minutes each day.

Although Wit & Wisdom is focused on content more than specific reading skills, the program provides companion books that are synched with Fundations, allowing students to practice decoding letters and sounds based on what they’ve learned in their phonics lessons. For students who need more help reinforcing phonics skills, the school works with an organization called Literacy Trust to offer more guided instruction one-on-one and in small groups.

But choosing a new curriculum is only the first step to overhauling classroom instruction, said Mathew Moura, an early literacy expert at Teaching Matters, an organization that partners with schools to improve instruction.

“I can buy everybody the greatest curriculum tomorrow and force everyone to use it,” he said, “but how they’re using it is really the heart of the matter.”

‘I am seeing impact’

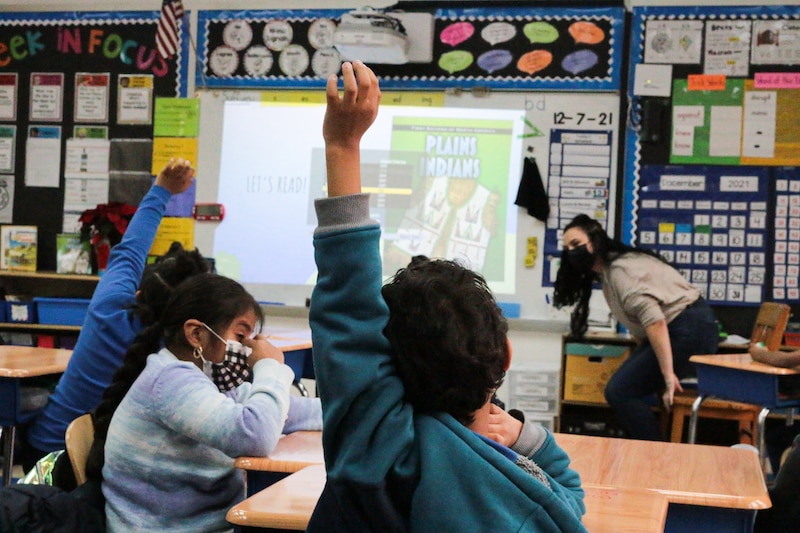

As a group of second graders returned from gym class, took squirts of hand sanitizer, and settled into their desks arranged in small clusters, their teachers nervously prepared to read one of the most challenging books they’ve introduced under the new curriculum.

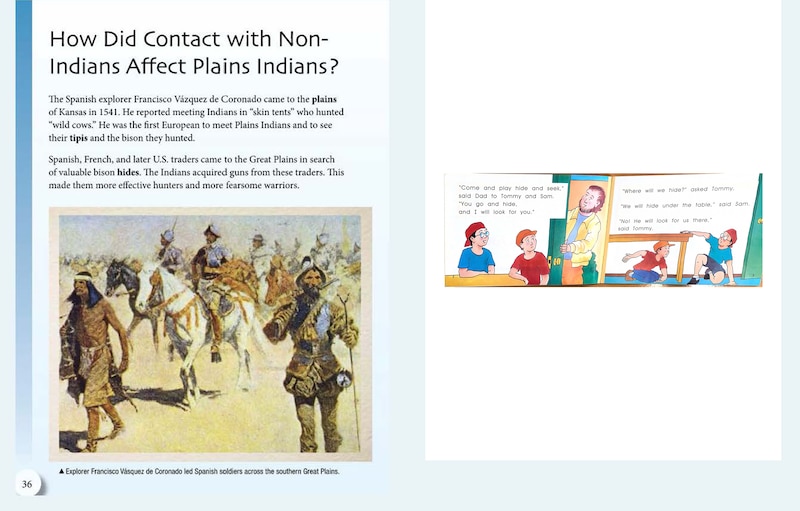

The 41-page book, called “Plains Indians,” is so dense that the teachers broke it into small chunks because they wouldn’t be able to finish it in one class period. That day’s reading focused on how Native Americans’ way of life was affected by white settlers who brought disease and violence and forced tribes to relocate to reservations. It’s far more complex than the books students could choose from under the Teachers College curriculum, which included topics like how animals use their tails.

Filiberti read much of the text out loud, taking frequent breaks to ask students questions like “What did the new settlers do to the buffalo?” and “When [Native Americans] were kicked out of their land what did they do?” With some prodding, students generally arrived at answers suggested in the text.

But when it came time to summarize the overall theme, the students struggled.

“What can our big idea be of this section, if I were to put all that in a sentence,” Filiberti asked. She’s greeted with silence and some murmurs. “What happened when the new settlers came?” Filiberti asked, reframing the question to be simpler.

“Probably killed, um, the buffalo,” a student responded.

“And they took their what?”

“Their teepees?” the same student said.

“Their land, right?” Filiberti said. “Let me know if you agree with my statement: ‘The new settlers took over the land and changed the Plains Indians’ way of life.’” With some nods of agreement, Filiberti moved on to read the next section aloud.

The lesson encapsulated some of the benefits and challenges of the new curriculum. The readings are difficult, but the school’s three second grade teachers said they are having more classroom-wide conversations since they’re all drawing on the same text, and students are making connections between each unit’s books, which are connected thematically.

Still, the teachers are trying to figure out how to make the denser reading more accessible.

“Wit & Wisdom as a curriculum is not learning how to read — it really is about the comprehension and exposure to different texts,” said Lauren Litman, a second grade teacher. “I think that’s our biggest struggle. We’re coming in assuming that the kids have the skills to do this.”

Compounding these challenges, many of the 7- and 8-year-olds in Litman’s classroom haven’t yet had a full school year uninterrupted by the pandemic, leaving many of them without practice holding a pencil, flipping through a physical book, or regularly interacting with classmates. The school’s second grade teachers often work to bounce ideas off each other and discuss tweaks to make lessons more accessible.

In one example, the curriculum didn’t call for learning some of the key vocabulary until after the students were already reading the text. “The curriculum does what they call ‘vocab deep dives’ but it’s usually after the lessons,” Litman said. “I was in day three or day four and a student said, ‘What are plains?’ and I felt so awful because they didn’t have that opportunity to know.”

When it came time for the more recent unit on civil rights, they spent a week reviewing key vocabulary words and watching videos about the history so they’d have more knowledge before jumping into the text, which was also at a slightly easier reading level.

“Building that schema made a difference,” Wolfe said. “I think the content in and of itself was a little more relatable.”

But even as students were more engaged, the lesson didn’t go exactly as planned. Wit & Wisdom lessons typically run about 90 minutes as written, yet the teachers only have about 50 minutes to devote to it on a given day, requiring that they make cuts. During the recent lesson about the March on Washington, they didn’t have time for a final assignment in which students were supposed to write in their journals about what they learned.

The teachers said they’re still adjusting to the new curriculum and are thinking about how to present the same lessons next year. It’s also clear that there are elements of the Teachers College curriculum that they don’t want to abandon entirely.

They miss the focus on genres like poetry. And they saw value in students’ being able to write more freely about themselves rather than focusing solely on responses to their reading. Most importantly, they are trying to still make room for independent reading.

For her part, Talukdar said no single curriculum is perfect. Transitioning to a new curriculum, she said, was always going to involve some trial and error.

“Quite frankly, this is a three-to-five-year process,” Talukdar said. “Based on what I’m seeing in classrooms, I am seeing impact.”

Moving a mammoth system

If improving reading instruction at a single school is challenging, doing so across the nation’s largest school system is a gargantuan task that has bedeviled previous administrations.

Under former Mayor Bill de Blasio, the city launched a “universal literacy” program designed to ensure all students were reading proficiently by the end of second grade by 2026. Hundreds of coaches were deployed to elementary schools to model lessons, give teachers feedback, and even “cajole” schools to rethink their approaches. (An analysis commissioned by the education department found that two years in, the program had a “small” but positive effect, though the city remains far from its goal of universal proficiency.)

To what extent schools have been making changes to how they teach reading remains unknown because city officials don’t track what programs schools use. In 2018, Chancellor Richard Carranza said the city’s literacy efforts still lacked coherence across different schools.

Banks, the new schools chancellor, is now indicating that he, too, wants to see changes in the way schools approach reading. In criticizing the Teachers College curriculum, he recently told reporters “there’s a very different approach that we’re going to be looking to take.” Still, he said he is committed to giving principals more autonomy over their schools and didn’t provide specifics about whether the department will pressure schools to make changes.

At the same time, the education department is investing more than $200 million in a culturally responsive curriculum that aims to include an elementary school reading program. Officials have not provided many details, including how it fits with their broader plans to improve literacy. Its full rollout, originally slated for fall 2023, is behind schedule.

If history is any guide, changes may come one principal at a time. At P.S. 236, Talukdar said principals who are considering a curriculum change should carefully consider whether their current reading strategies are working and shouldn’t expect change to come quickly.

Overhauling a curriculum “can be taxing to school leaders because there’s just so much information out there,” she said. “But is it ideology that we’re stuck with, or is it what’s going to really help our kids with that goal of being proficient readers?”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org