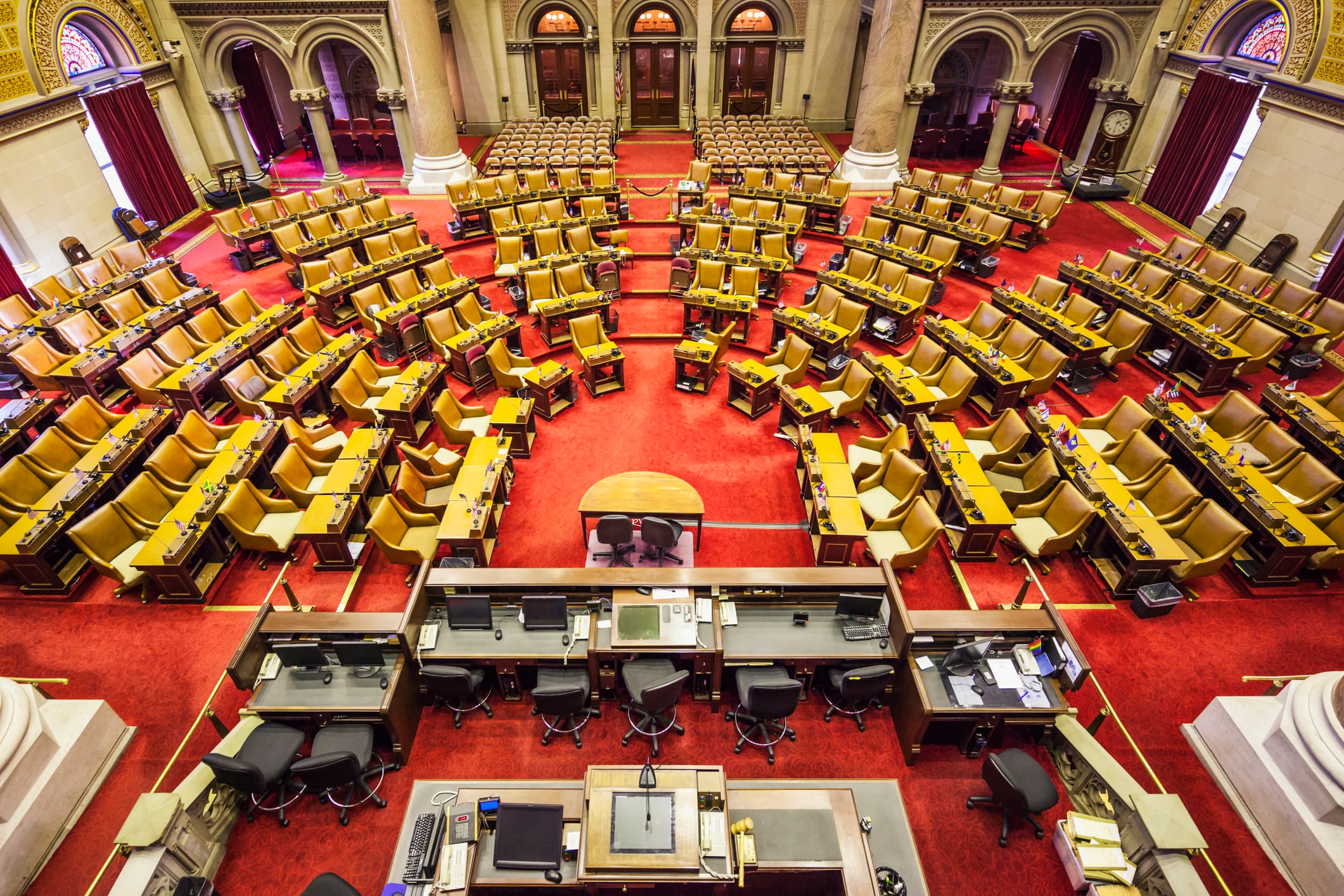

New York state lawmakers passed a budget over the weekend that will boost funding for New York City schools by about 4% per pupil next school year.

The city’s public schools will receive just over $12 billion in state funding. State funds represent roughly 40% of the city’s education operating budget.

School funding is usually a bitter battle among lawmakers and advocates during budget season. But lawmakers reached a deal last year to fully fund Foundation Aid, the formula that sends more dollars to high-needs schools.

As a result, even the most fervent school funding advocates shifted their attention to expanding other programs and initiatives. One of the largest pushes went toward expanding subsidized child care across New York.

The final budget deal calls for $7 billion in early child care funding over the next four years, which could pave the way for universal child care and greatly expand access for New York City families. But some advocates and lawmakers were disappointed by that level of funding and are frustrated that it still excludes children who are undocumented.

Lawmakers also passed legislation to mandate electric school buses and instituted some funding changes for private special education programs, which serve public school children with the most challenging disabilities and have been struggling to retain teachers.

Here are highlights from the state budget.

NYC schools get $56 million less than proposed

New York City schools will see about $475 million more in state funding next school year. That figure is $56 million less than what Gov. Kathy Hochul had proposed; it wasn’t immediately clear why the final budget sent less money to the city.

Unlike previous years, it was clear from the governor’s proposal in January that school districts would receive an influx of cash following commitments last year to boost Foundation Aid, which gives districts the most flexibility, including the ability to hire more teachers or create new programs.

Some advocates, however, were disappointed not to see a funding increase for career and technical education programs. The New York State Educational Conference Board, a coalition of large school organizations, including the state teachers union, had called for updating a three-decade-old formula that helps fund career and technical education. The state’s Board of Regents also asked for more funding.

“Completing high school should put every young person on a path toward success in adult life,” Charles Dedrick, executive director of the New York State Council of School Superintendents, said in a statement. “Quality CTE programs have proven to be an effective option for students, including those planning to enter the workforce, to pursue further education, or both.”

Thousands more NYC families will be eligible for subsidized child care

The state’s $7 billion, four-year agreement for expanding subsidized child care would make it more affordable for families earning up to 300% of the federal poverty limit, or around $83,000 for a family of four. Previously the upper limit was around $55,500 for a family of four, or 200% of the poverty level.

While the final deal did not make care free, keeping in place co-payments that advocates had hoped would be eliminated, those payments are now capped at 10% of a family’s income.

About 74,000 more New York City children under the age of 5 will be eligible for significantly subsidized care, for a total of about 290,000 children across the five boroughs, according to an analysis of 2019 Census data conducted by United Neighborhood Houses, which represents child care providers.

Children who are undocumented will not be included, leaving an estimated 5,000 children across the state excluded from the program. Because state and federal dollars are “co-mingled” for subsidized child care, covering undocumented children would violate federal law, according to a spokesperson for Hochul’s office.

But advocates believe officials could separate out state funds and use them specifically for excluded children. It could work like the state’s excluded workers’ funds, which provided benefits to New Yorkers who lost work during the pandemic but were left out of federal relief programs, said Gregory Brender, director of public policy for the Day Care Council.

Many advocates called the investment “historic” for the industry and for families desperately in need of support. But some who had called for even more funding said the plan will fall short and cause families long waits for subsidized care — leading at least one leading lawmaker behind the universal childcare push, Sen. Jabari Brisport, to vote against the budget.

New York City in recent years has significantly expanded free child care for 3- and 4-year-olds through free preschool programs, but families with infants have struggled to find and afford care.

It remains to be seen how many families will take advantage of more affordable care and how the rollout will work. In 2019, more than 93,000 families qualified, yet only about 8,000 were enrolled in publicly supported programs, according to public data analyzed by the Citizens’ Committee for Children, or CCC, a nonprofit advocacy group.

The annual cost of care is about $18,000 to enroll in center-based programs or about $10,000 for programs that are run out of providers’ homes. Many women who left the workforce during the pandemic have not returned, with 35% of those reporting lack of childcare as the reason, according to census data analyzed by CCC.

Providers, meanwhile, have struggled since well before the pandemic. Many operate as private businesses, while those that participate in public programs say the rates they’re paid do not come close to covering costs. COVID only made things more difficult, with more expenses and plummeting enrollment. Many were forced to close.

Districts will start purchasing electric buses

The final budget requires all school districts to use zero-emission school buses that don’t use gasoline by 2035. Starting in 2027, districts can only purchase or lease green buses, or they must require the same of companies they contract with for transportation services.

This follows a law passed by New York City Council in November 2021 requiring that all school buses in use are zero-emission by 2035. Roughly 10,000 school buses service New York City, according to the New York State Association for Pupil Transportation, or NYAPT.

Former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio had committed last April to changing 75 of 960 city-operated buses to electric by 2023, costing $30 million. The city contracts with other companies to run other school buses. An education department spokesperson said there have been no changes to de Blasio’s commitment.

Hochul had pitched the change in her budget proposal in January, earning pushback from NYAPT and other school advocates over the complicated logistics that could arise from the mandate. The groups worried about the costs that would come along with the mandate, such as building charging stations.

To meet the mandate, a district without any electric buses would have to convert close to 8% of its fleet on average annually in order to meet the new requirements by 2035.

NYAPT estimated the new mandate will cost at least $1 billion a year across the state, assuming about 4,000 new zero-emission buses are purchased annually. That organization had called for allowing districts to convert 5% of their fleets annually beginning in 2029, or pushing the start date of the mandate out to 2035, while letting districts choose a fleet of all-electric school buses or “a diversified fleet of school buses is more appropriate when considering the safety, environmental, and economic factors of their school district.”

A spokesperson for the association did not immediately share its response to the final budget.

The budget dedicates $500 million for zero-emission school buses in the state’s environmental bond act, a borrowing plan that must still be approved by voters this November. It also allows districts to apply for a two-year extension to meet the requirements of transitioning their fleets.

Dedrick, from the state’s superintendents group, said the $500 million allocation “will be a significant help to school districts.”

Private special education funding

Advocates and education policymakers had hoped for changes in how New York funds state-approved, privately run special education programs that serve thousands of school-age and preschool children with severe disabilities.

But those requests didn’t make it into the final budget.

Advocates welcomed a commitment from Hochul to boost funding for these programs by $240 million. But there was no final deal to freeze a complicated policy called “reconciliation,” which they argue could make the funding increase moot.

Under reconciliation, not only must programs return state funding they don’t use in a given school year, they also lose that funding in the following year. That means, for example, that if a teacher quits, and the school is unable to hire a replacement, then the school will not get the money for that position in the following year, said Chris Treiber, associate executive director for children’s services at InterAgency Council of Developmental Disabilities Agencies, Inc., which represents these programs.

“Our schools are so understaffed, they’re unable to recruit teachers, teacher assistants and clinicians,” Treiber said. “If they had to spend all this money in one fiscal year, they never would be able to.”

Last school year, 853 schools which serve school-age children had a teacher vacancy rate of 29%, while preschool programs had a vacancy rate of 33%, according to figures from Treiber’s organization.

The final budget allows these programs to retain a certain portion of unspent funding. Over the next three years, schools can hold on to up to 11% of surplus funding. That percentage would decrease to 8% in the 2025-2026 school year, to 5% the following year, and then 2% by 2027-2028 and annually after that. Treiber said his organization is still working to understand how exactly this would impact their programs.

Stagnant state funding has contributed to the closure of these programs and a shortage of seats for 3- and 4-year-olds with disabilities.

More than 22,000 New York City children are enrolled in these programs. Rate increases for the preschool special education programs stalled after the 2008 recession. Since 2015-16, the state has approved a 2% annual rate increase, which trails what public schools and programs for older children have received.

Hochul vetoed a bill in December that would have provided preschool special education programs with the same annual rate increase that school districts receive.

On Monday, State Education Commissioner Betty Rosa said she’s concerned about these programs closing due to funding issues, leaving children with the most severe disabilities with fewer options. Her team also requested just over $1 million to begin reviewing the tuition rate-setting methodology, but that, too, was left out of the final budget.

“While we are still looking at this issue, we do believe the tuition rate setting methodology is one that has to be addressed,” Rosa said. “We are hopeful we can continue the dialogue because there has to be a full understanding of the long-term implication this has.”

More mental health and tuition help

A total of $100 million in state grant matching funds will be available over the next two years to match what school districts are spending to address the fallout from the pandemic, including for student mental health and academic recovery. Hochul pitched this in her budget proposal in hopes of helping school districts address a youth mental health crisis spreading across the nation.

That funding will match what school districts are spending, including on extended day and after school programs and hiring mental health professionals.

The state will also spend $150 million toward New York’s Tuition Assistance Program in order to help cover tuition for 75,000 more part-time college students.

Christina Veiga contributed.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.

Correction: This story previously stated the state has expanded free child care. In fact, more families will now qualify for subsidized care, but families will still be required to contribute a co-payment capped at 10% of their income.