This is part of an ongoing collaborative series between Chalkbeat and THE CITY investigating learning differences, special education, and other education challenges in city schools.

New York City will require all elementary schools to adopt a phonics-based reading program in the coming school year — a potentially seismic shift in how tens of thousands of public school students are taught to read.

The announcement came as part of a wider $7.4 million plan by Mayor Eric Adams to identify and support students with dyslexia or other reading challenges, including screening students from kindergarten through high school and creating targeted programs at 160 of the city’s 1,600 schools.

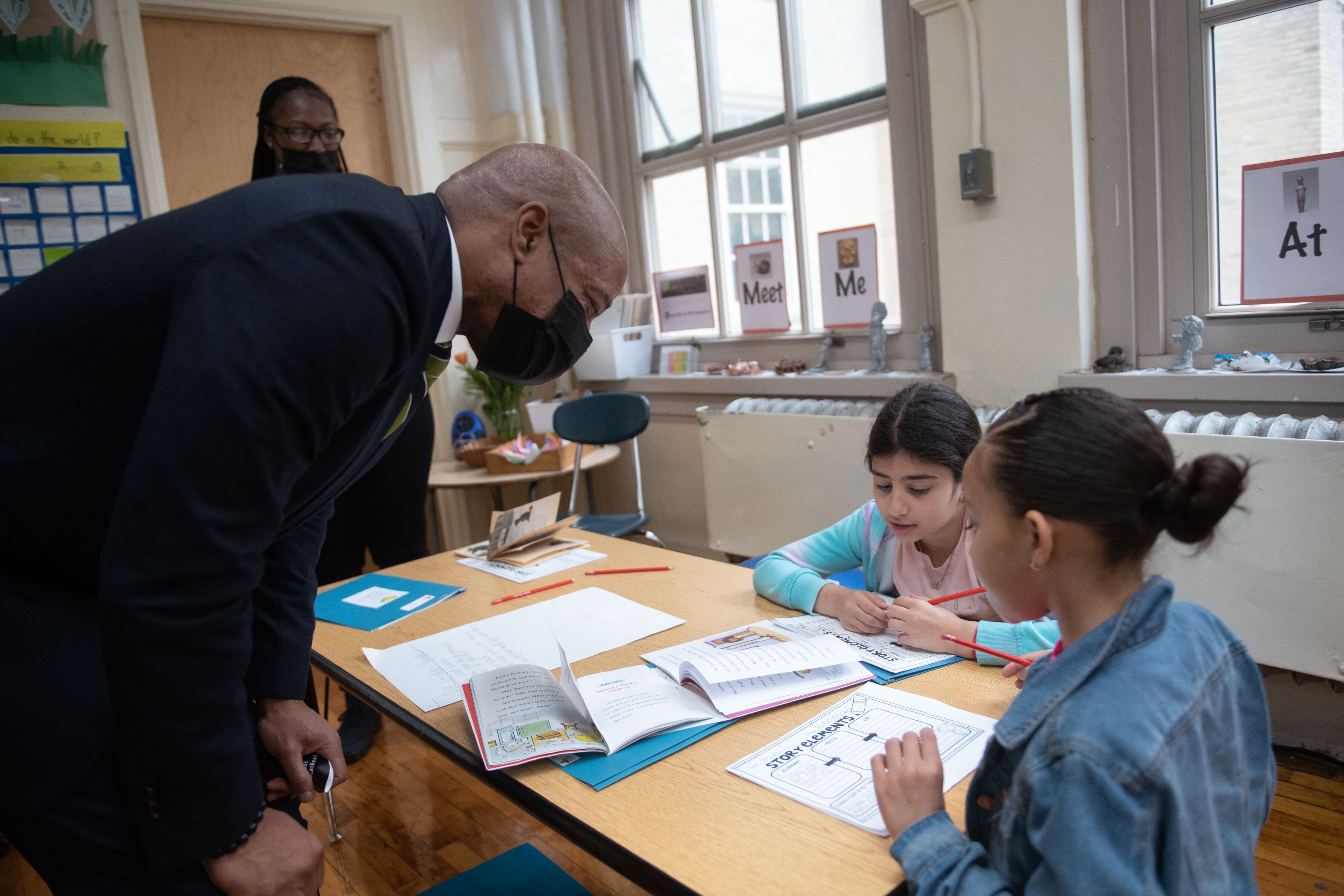

“We’re going to start using a proven, phonics-based literacy curriculum that’s proven to help children read,” Adams said at a press conference at Harlem’s P.S. 125. “This is our opportunity to really move the needle on something that has been impactful for our children for a long time.”

City officials said teachers will be required to implement one of the education department’s recommended phonics-based curricula for kindergarten through second grade as part of the initiative. This shift is a major change in approach, as the department traditionally defers to principals on curriculum choice, with widely varying results.

Thursday’s announcement represents a significant victory for parents — some of whom wept at the press conference — who have long been frustrated with the city’s inability to educate many struggling readers. Some families have sought outside evaluations, which can run thousands of dollars, and sued the city for private school tuition reimbursements, a process that often requires significant time and resources.

City officials are now vowing to better equip educators across the nation’s largest school system to serve students with reading challenges. They plan to launch programs specifically geared toward students with dyslexia at two elementary schools and provide deeper support for students at 80 additional elementary schools and 80 middle schools.

The efforts are intended to help address one of the city’s most entrenched problems: Just over half of students in grades 3-8 are not proficient readers, according to state tests. Profound learning disruptions caused by the pandemic have only amplified concerns that students have been knocked off track.

Adams often speaks about his own struggles with dyslexia and promised on the campaign trail to make it a priority. He framed the announcement Thursday as a “first-of-its-kind” effort and even as a bulwark against incarceration.

“Dyslexia holds back too many children in school, but most importantly in life,” Adams said. “Dyslexia is not a disadvantage. It’s just a different way of learning. And all the children need — they need the tools to know how to comprehend information.”

‘Watching our children’s suffering’

Adams shared his personal story of how his peers would tape a sign on his chair that read “dumb student,” which made him want to avoid school. And, indeed, some of his friends dropped out because of their learning struggles, he said.

But with his mother’s support, Adams pushed ahead, and he acknowledged the emotional toll on parents forced to advocate for their children and fight with public schools unable to provide the proper support.

Two groups of parents have been working on creating programs for students with dyslexia and other reading-based challenges. Literacy Academy Collective in P.S. 161 in the Bronx and Lab School for Family Literacy in P.S. 125 in Manhattan will both offer specialized programs for students with dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities. The DOE will immediately move to build programs at additional schools with the goal of having at least one school offering specialized instruction in each borough by fall 2023.

Some experts estimate that 10% to 20% of children have some form of dyslexia, while others put the figure much lower. Regardless, many literacy experts argue that systematic reading instruction emphasizing phonics is beneficial for all students who may struggle with reading, regardless of whether they have a specific diagnosis.

Naomi Peña, a mother of four children with dyslexia and one of the forces behind the program set to open in the Bronx, talked about how “watching our children’s suffering” inspired her to team up with five other moms to create the new endeavor.

“I was desperate to find support,” she said, fighting back tears. “My only option was costly tutoring programs because my children’s learning styles could not be met in the classroom.”

City officials are promising to reach other students by ramping up efforts to train all teachers on how to identify and support students with dyslexia. By April 2023, teachers in all subjects will participate in a two-hour introductory training created by Made By Dyslexia. Educators will also have more opportunities to be trained in evidence-based phonics programs, including Wilson and Orton-Gillingham. Additionally, all grades will have access to literacy coaches in targeted schools, officials said, though it was not clear how many.

“Literacy cannot be a skill that is relegated to a class, and we must support educators in every subject area to become allies in the work of making sure that every child can read,” said schools Chancellor David Banks.

Return to phonics

Banks has consistently said he wants a heavier focus on phonics. In March, he made waves by arguing a popular Teachers College reading curriculum that was previously embraced by the education department “has not worked.”

The city will offer a few options for schools to choose from such as the PAF Reading Program, Ready for Reading, and Fundations. The phonics program will need to be paired with a comprehensive literacy program, officials said.

This effort is separate from a previously announced initiative to create a universal culturally responsive curriculum known as Mosaic, which will focus more narrowly on middle schools and be available by fall 2023.

During the Bloomberg administration, then-Chancellor Joel Klein pushed schools to use a reading approach known as “balanced literacy,” which has increasingly come under fire for failing to emphasize systematic instruction on the relationships between sounds and letters. Twenty years later, that model remains entrenched in many schools.

The city does not centrally track what curricula schools employ, but officials believe that roughly 200 of the city’s 700 elementary schools do not currently use phonics-based instruction, according to a Department of Education spokesperson. They also believe that dozens, or even hundreds more, are not implementing phonics as effectively as they should, despite a growing consensus among experts that explicitly teaching the relationships between sounds and letters is crucial.

Changing a literacy curriculum is no easy process and can be challenging without buy-in from educators and solid training. The education department pledged to provide ongoing professional development throughout next year to help with the shift.

For the screening, children will be assessed on literacy three times a year, and those who continue to struggle will have access to a more targeted screening for dyslexia, Banks explained. The city will continue using a tool called Acadience Reading, the latest iteration of an assessment known as Dibels (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills), which was implemented this year for kindergarten through second grade.

City officials did not immediately say how they will measure the initiative’s effectiveness.

The plans “could have a transformative impact if implemented well,” said Kim Sweet, of Advocates for Children, which has spent decades fighting for low-income students who are struggling with reading and are unable to be supported in public schools.

Her organization looked forward to “digging into the details” and working with the education department so that “all children learn to read, no matter where they go to school,” she said in a statement.

The city is also creating a task force on dyslexia, and Adams said he is working with Public Advocate Jumaane Williams to push for dyslexia screening in jails across New York state.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.