Nestor Rivas grew up near the South Bronx’s sprawling St. Mary’s Park, where families host barbecues and children play baseball.

But it wasn’t until Rivas began researching the park as part of a new urban planning curriculum at his school, that he realized something: Unlike Central Park or Union Square, St. Mary’s doesn’t have food vendors.

“You go to different parts of uptown Manhattan, and they have these parks with foods and like, these farmer’s markets,” said Rivas, 18, a senior at Laboratory School of Finance and Technology in the South Bronx.

That disparity didn’t exactly upset him, he said, “but more so, I questioned it.” So Rivas and eight other peers dreamt up a proposal to create food kiosks at the park that they could rent out to local restaurants.

It’s a first-of-its-kind curriculum in New York City’s public schools that got Rivas thinking more deeply about his local park, where there have also been concerns about drug use and sanitation — two issues other students highlighted. Launched by New York City’s Department of City Planning and molded by four government teachers, the 12-week pilot course taught Rivas and roughly 60 of his peers about how to advocate for their neighborhoods and what a career in urban planning looks like.

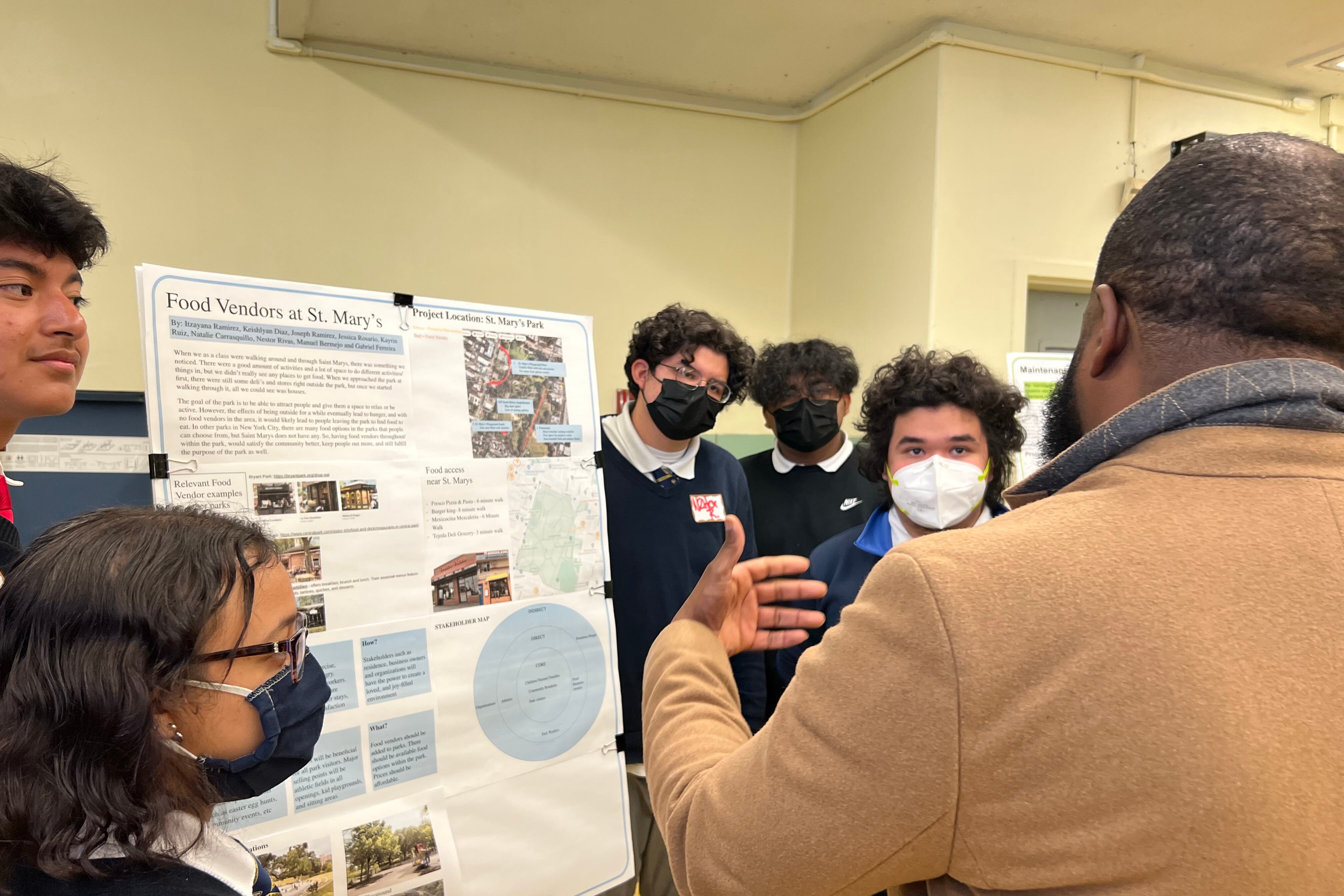

The course culminated in a fair last week in the school cafeteria, where they pitched ideas to city officials and lawmakers. Their ideas were based on “real stuff — the stuff of life,” said Adolfo Carrión Jr., commissioner of the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, who inspected various projects and talked to students last week.

“The kids understood that if you’re in the park with your children or your family or your friends, you have to walk 7-10 minutes to get a snack or something to drink, so they said, ‘Why don’t we built the kiosks, rent them out, and people can start businesses, and it can give a family the convenience and safety of keeping the kids there,’” Carrión, former Bronx borough president and city councilman, said of the food vendor project. “That’s really super-practical stuff and really cheap to implement.”

The course began to take shape last year, when a team of city planning officials who focus on increasing outreach to local communities emailed schools about creating lessons around urban planning. The four government teachers at Laboratory School of Finance and Technology seemed to have the most interest in taking on such a project, planning officials said.

In February, the urban planning curriculum became a part of three government classes at the school. First, students shared what they thought the South Bronx had to offer and what it needed more of. Then, planning officials told the students about what urban planning is, and how advocacy works. Teachers surveyed the students to see what projects they wanted to pursue, and they landed on three things: St. Mary’s Park, affordable housing, and a new jail site that’s coming to the neighborhood as part of a de Blasio administration plan to replace Rikers Island with a smaller network of borough-based jails. Each class focused on each of those topics.

With the help of planning officials who visited every week, the students did what an urban planner or a developer might do. They came up with project ideas, researched and gathered data to make their arguments, and identified the people who would be affected by their proposals. At one point, they took on various roles to simulate the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure so they could understand the formal process behind making a proposal come to life.

Students took on various roles, such as developers and city planning commissioners, and some completed the class wanting to improve their public speaking skills, planning officials said.

High school seniors are usually checked out by this time of year, said Juan De Jesus, one of the teachers who led the class. But these students stayed interested because they were proposing their own ideas and therefore felt “that they can actually have a real impact.”

At one point, De Jesus’s students asked him whether city officials would take their ideas seriously.

“If you guys don’t care about it, and you guys are just thinking this is just another assignment for a grade, then why would I want to invest in your ideas if you’re not invested in it yourselves?” De Jesus recalled telling them. “And I think that was kind of the reality check for them, and they were like, ‘OK, I really do have to care about this, or no one else will.’”

Asked if he would take any of the ideas he saw at the fair seriously, Carrión said, “Absolutely.”

On the day before the fair, students sat in their groups with their completed presentation boards loaded with pictures, data, maps, and diagrams. Then they rehearsed their presentations.

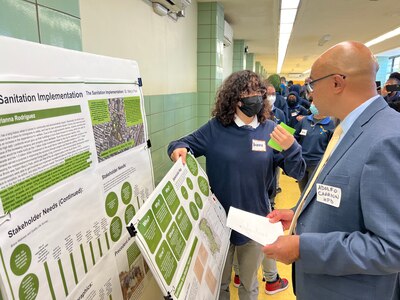

Brianna Rodriguez, 17, opened her practice elevator pitch with, “OK, so this is my proposal,” which was about improving sanitation in the park. When she finished, two planning officials in the class encouraged her to instead open with her story about seeing dog poop and syringes on the ground.

So when Rodriguez made her pitch to Carrión during the fair the next day, she began by saying, “I went to the park this weekend, and the sanitation was not that great.” The commissioner responded by telling Rodriguez that she’d done “nice work.”

It’s unclear if the class will return at the school or if it will be expanded. Planning officials are going to analyze the program and get feedback from the school on what worked and what didn’t before making a decision.

Rodriguez, who’s heading to college this fall, said the class didn’t persuade her that she should become an urban planner. But she felt like she “actually contributed something” to the community by coming up with her idea. She has dreams of opening a community center where Bronx residents can get therapy, and she thinks the class gave her some insight into the work she’ll need to do to make that happen.

Rodriguez did say the class required a lot of research and work, which was tough to juggle. At the same time, she said she now understands how much work goes into planning projects across the city.

“We’re going to college soon, so I feel like it is time we start stepping up to the real world, and I really like that we got, like, a little piece of what it’s like inside the Department of City Planning and how we can be potential contributors to the future,” she said.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.