The Trevor Project offers 24/7 LGBTQ mental health support toll-free at 866-488-7386. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has trained crisis counselors available at 800-273-8255 or by texting 741741.

For Julie LaMendola, the 45-minute morning commute from Bushwick, Brooklyn, to drop off her 5-year-old at a school in Manhattan’s East Village, plus the 30-minute solo trip back, is exhausting, but worth it.

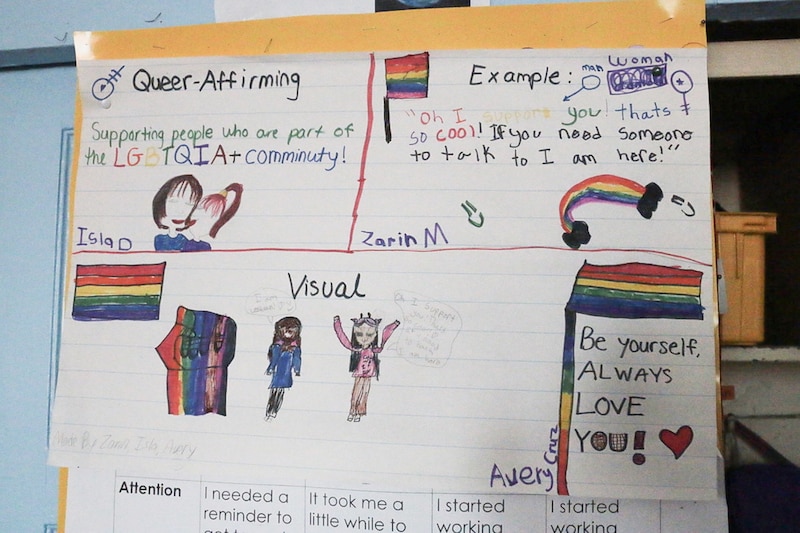

At the Neighborhood School — a small and progressive public school with some staffers and students who are transgender — educators start as early as kindergarten incorporating age-appropriate ways to discuss gender identity and preferred pronouns, parents and educators there said. LaMendola, whose partner is transgender, feels fortunate to have found a school that is helping her child develop into a kind and thoughtful human who doesn’t feel “weird” for being part of a queer family.

“They feel like they can ask questions and be who they are,” LaMendola said. “I think there’s less bullying when each of them is honored as a person, as an individual.”

While other parts of the country have seen a wave of new restrictions over teaching about gender identity, the nation’s largest school system has taken the opposite approach, adding an array of programs to support trangender and nonbinary students.

But like most things within the nation’s largest school district, what happens across the city’s 1,600 schools often varies school to school and even classroom to classroom.

The city’s education department offers an LGBTQ+ curriculum to supplement existing history lessons, and it provides ongoing professional development opportunities for school staff, among other support for LGBTQ students, officials said. There are Gender and Sexuality Alliance clubs at all grade levels that provide spaces for students to freely speak about their gender identities. The department also provided direct funding to roughly 200 schools this year to establish identity-based electives.

“We are proud to support and accept all of our young people,” education department spokesperson Suzan Sumer said in an email. “All NYC public schools are encouraged to provide resources and programs in support of LGBTQ+, non-binary and transgender students, staff, and community members.”

New York City began putting guidance in place for transgender students nearly a decade ago, and continues to update and expand it, education officials said. The city and state’s approach stands in stark contrast now to places like Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law in March prohibiting lessons on sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade, and more than a dozen states that are considering similar proposals, part of a recent upswing in anti-LGBTQ legislation led by Republicans nationwide. In Texas, a court paved the way last month for the child welfare agency to investigate parents for abuse if they provide gender-affirming care.

In New York, on the other hand, state guidance says that schools can determine whether to share a student’s gender identity with their family based on the student’s safety.

And while New York has protections in place, anti-transgender backlash still touches city schools, according to officials who worry about threats made to schools that incorporate gender identity discussions into the classroom.

‘How do we get the resources?’

The number of youth ages 13-17 who identify as transgender has nearly doubled over the past several years nationwide, according to a report released this month from the Williams Institute, a research center housed at the University of California, Los Angeles law school. (The new report looked at government health surveys from 2017 to 2020 and did not include data for children younger than 13.)

Nearly 1 in 5 people who identify as transgender nationwide — or roughly 300,000 — are ages 13-17, with New York having the highest numbers, the June report found. About 3% of youth in New York are transgender.

Gregory Payton, a professor of psychology at Columbia University’s Teachers College and a clinical psychologist specializing in mental health for LGBTQ youth, said he noticed a marked increase in the number of gender noncomforming, gender nonbinary, or transgender youth in the past few years in part, he thinks, because parents and society have become more accepting.

But still, he said “enormous stigma” remains. Few educators have been trained specifically on gender identity, and many may, “consciously or unconsciously, view their students through a gender lens and then knowingly or unknowingly gender their students,” Payton said.

Though demographic and mental health data remain limited, the LGBTQ suicide prevention nonprofit Trevor Project recently surveyed an estimated 34,000 LGBTQ youth ages 13-24 across the nation, finding that nearly 20% of transgender and nonbinary youth attempted suicide in the past year, with higher rates for youth of color compared to their white peers. For LGBTQ youth who live in an accepting community, people reported significantly lower rates of suicide attempts, the survey found.

Consistent with the research, Payton is seeing alongside the rise in gender nonconforming, gender nonbinary, and transgender youth, an uptick in anxiety, depression, and stress. He worries there aren’t enough clinicians trained to work with such young people.

“Our field is really unprepared for this,” Payton said of the psychology community. That could have a spillover effect onto schools that are also grappling with how to best support students.

“It’s remarkable how much a student’s experience can vary based on the teacher or principal … It’s not that the schools don’t want to do something or don’t care. As with everything in education, it’s: ‘How do we get the resources?’” he said. “Everyone is trying to scale up for this and develop more competency around it. But of course in that process you’re going to have students who don’t get the support they need.”

‘He didn’t feel safe there’

For Jean, a mom on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, her child was already aware that he was a “different kind of he” at the age of 3, she said. She communicated this with his teachers at P.S. 290, but never felt her first grader’s school fully supported him. (For privacy reasons, the mom asked to use her middle name.)

Students from P.S. 290, a National Blue Ribbon school, recently participated in a local showcase sharing how their learning supported their ability to address issues of racism, sexism, and homophobia, according to education department officials. Yet, Jean felt like the school dismissed or ignored her son’s needs as a transgender person.

This year’s initial class assignment — the story of the child’s first name — may have seemed innocuous, but the project was upsetting for a child who changed his name, Jean said. Another child in the class also knew her son when he used his deadname, or what some transgender people call the name they were given at birth. Jean felt the school did not use that as a teaching moment.

“My child could have transformed the school for the better,” Jean said. “Instead he didn’t feel safe there.”

Her son, who also has a learning disability, had struggled with school refusal since starting at the school in 2018 for pre-kindergarten. He missed a number of days and had to repeat kindergarten. The mom agreed with the move, hoping to give her son a fresh start.

Jean’s relationship with the school grew increasingly fraught over the years, and in February of this year, the school reported her for educational neglect. A caseworker from the Administration for Children’s Services closed the case as soon as she helped Jean get her child a therapist, after having been wait-listed for months. The mom pulled her first grader from the class in March to home-school him.

“It’s not an ideal situation, but I don’t feel like I have a choice,” she said of home-schooling her child. “With a learning disability on top of being trans, knowing that a child is a little bit different — yet they kept looking into my home for the problem. My child didn’t want to be in that school. What were they doing to make my child want to be there?”

Jean filed a complaint last week with the U.S. Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights for alleged discrimination on the basis of sex, disability, and retaliation. P.S. 290’s principal did not respond to questions.

The education department said the school follows citywide guidelines that say “schools must be proactive in creating a culture and practices that respect and value all students and foster understanding of gender identity and expression within the school community.”

‘Let’s figure it out together’

Jean’s experience felt dramatically different from the kindergarten classroom where LaMendola sends her daughter.

During the first week of school, each child at the Neighborhood School received a teddy bear, a comfort object to follow the children through each grade that is part of a social-emotional approach created by a Bank Street College professor and author Lesley Koplow. As an early community-building activity, the teacher asked the children to give their bears names and ages, and in creating her own take on the project, she also asked for the bears’ pronouns. Students could choose from an array: girl, boy, both boy and girl, neither boy or girl, something else, or not share anything at all. The students were also asked to give the same information for themselves.

For LaMendola, it felt like a safe way for children to express their identities and, she hoped, helps her daughter feel accepted. Her daughter uses she/they pronouns.

Dianne Pannullo, a 21-year veteran Neighborhood School teacher who leads LaMendola’s daughter’s class, had been incorporating teddy bears into her joint kindergarten/first grade class for a while, but only added the pronouns two years ago. She was inspired by a colleague who disclosed they were nonbinary and changed their name while working at the school. The colleague shared their experiences about growing up and not identifying as a girl or boy, and how important it was for colleagues and friends to use their new name.

“They brought a lot of knowledge to us,” Pannullo said about incorporating gender identity into the lesson with the bears. “We’re doing it and learning and changing it as we go.”

The school also has a bi-monthly LGBTQ support group called the Rainbow Coalition. Some teachers felt it was important to address gender identity in elementary school after they talked to adults who said they already knew their identity in kindergarten or first grade, Pannullo said.

“Kids are so clear. When you have a transgender kid, they are not confused by who they are,” she said.

Sometimes schools stay away from teaching about gender identity because they perceive it as too controversial, but Payton, the psychologist, believes that schools are already talking about gender identity — even if they don’t know it.

“We just talk about it in ways that are stereotypical, and if internalized, to a great extent it can cause a lot of distress,” he said. “Parents don’t fully grasp how much competency or fluency or awareness of gender their kids have at a young age.”

LaMendola understands why some families might struggle with it.

“Some adults are like, ‘I don’t get it, they’re so young.’ This is the exact time you should talk to your kid. It’s about honoring your child and letting them know you’re there for your child whatever they are,” LaMendola said. “I think parents don’t like it because it makes you have to talk about things you don’t know how to explain. But that’s all of life. Let’s figure it out together.”

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.

If you are having trouble viewing this form on mobile, go here.