Martin Urbach began a recent morning by meeting with the parents of a student who threw a book out of a fourth floor window, nearly hitting a woman pushing a stroller.

Not long after, Urbach, the restorative justice coordinator at Manhattan’s Harvest Collegiate High School, dispensed advice to a distraught student who camped out in his office instead of going to class. That afternoon, he was off to lead a mediation with a group of boys who had been displaying behaviors more common to middle schoolers, including pulling each other’s pants down during a recent field trip.

“This is the hardest school year I’ve ever experienced,” Urbach said. “I think all of us in a way [have] forgotten what it means to be in community. It’s like 500 people who are traumatized and are starved for connection.”

Harvest is one of hundreds of schools across New York City that have embraced restorative justice, a philosophy rooted in giving students and staff space to share their feelings and talk through conflicts instead of resorting to more punitive measures like suspensions.

Many school leaders leaned on those tools this year, the first since March 2020 requiring the return of all students — many of them bearing deep emotional and academic scars. Some students were withdrawn and depressed while others acted out as they reacclimated to in-person classes. But even schools that prided themselves on using restorative justice to address students’ needs struggled to pick up where they left off before the pandemic.

On some campuses, including Harvest, leaders continued to emphasize restorative justice by devoting more staff resources to it, restarting student-led mediation, and giving students regular opportunities to reflect on everything from their anxieties about grades to the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

But other school leaders struggled with how to address disruptive behavior when programming like mentorship or advisory programs had atrophied, sometimes backsliding to more punitive forms of discipline.

“Things have been more challenging this year by several orders of magnitude,” said Tala Manassah, the deputy executive director at the Morningside Center for Teaching Social Responsibility, which helps implement restorative justice programming at hundreds of schools, including in New York City. “The pain that kids are coming to school with I think is unprecedented.”

City officials appear to be doubling down on restorative justice thanks to an influx of federal dollars, more than tripling funding over a three-year period to $21.6 million next fiscal year, according to the Independent Budget Office.

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio promoted those efforts, alongside reforms to the discipline code, as a way to address disproportionate suspension rates among Black students and those with disabilities. Suspensions have fallen by more than half over the last decade, but those moves were controversial, as some educators said the reduction in suspensions without wider buy-in and training in alternative approaches created more chaotic classrooms on some campuses.

The current administration’s plans are less clear. The restorative justice funding remains in the budget and schools Chancellor David Banks recently said he does not favor zero tolerance approaches. But education department officials declined interview requests and did not respond to written questions about their plans, including whether they’re moving forward with expanding restorative justice programming to all middle and high schools.

“My sense is there is a continued commitment to this work,” Manassah said. “But the devil is always in the details.”

‘It feels like it’s not working’

Before the pandemic, Lyons Community School Principal Taeko Onishi worked hard to set a welcoming tone, greeting students outside the school’s main entrance with hugs and high fives. She was also an early adopter of restorative practices, building those tools for more than a decade.

But much of that work felt like it evaporated this school year.

“There’s a lack of trust that’s different than anything I’ve seen in years — it manifests in fights,” Onishi said. “It’s like we weren’t there for them for so long, and now we have to rebuild that.”

Onishi pointed to a series of interlocking problems. Students returned with acute mental health needs after the pandemic hit many of their families hard. Some were rattled by violence in their neighborhoods, including one student who was recently shot in the ankle off campus and has stayed home ever since out of fear of commuting. A more significant chunk of students had never attended the 6-12 grade school in person when they arrived this year, meaning there were fewer students who were used to the school’s norms and could act as role models.

The school also focused less on restorative justice during the last two years, such as training students to mediate conflicts, since most students were learning from home and staff were stretched thin.

“It used to feel like [students] would come and talk to you and let you calm them down — or they’d be willing to do a mediation,” Onishi said. Now even minor issues spiraled out of control, and students were less likely to intervene with friends as they had previously.

“The smallest slight can set it off,” Onishi said. “It’s like, ‘Why did you punch them in the face?’ and it’s like, ‘Because they looked at me.’”

That sense of instability created pressure on the school’s leadership. Parents became more worried about their children’s safety in the building, which in turn made them “believe less in the possibility of reconciliation,” Onishi said.

Staff support for restorative justice approaches frayed too. Responding to a growing number of fights felt like whac-a-mole while teachers were stretched thin and burned out, especially during coronavirus surges that left them scrambling to cover their colleagues’ lessons.

Despite her commitment to deploying alternatives to suspensions, Onishi has been quicker to issue them this year, a move she feels conflicted about.

“You need to keep your school safe, right?” she said. “It’s definitely not a long-term solution. But it’s a short-term solution, and so you do it. You need time to recover from whatever happened.”

Overall, principals across the city did not lean more heavily on suspensions. Schools issued 16% fewer suspensions during the first half of the academic year compared to the same period in 2019. And reports of fights dropped 27% through May of this year compared with the 2018-19 school year, an education department spokesperson said. More serious infractions declined 10%.

Still, those statistics may mask significant variations between schools, and several experts and educators said they’ve seen more disruptive behavior. There has also been an increase in weapons confiscated at schools, including firearms, though some of the increase is likely related to bringing items like pepper spray for safety when they’re off campus, students have said.

Despite relying more on suspensions this year, Onishi said the experience only made her more committed to restorative programs.

The school refilled its youth advocate positions, adult staff who implement restorative practices. They are redoubling efforts to train students as mediators. And the school is giving extra help to teachers who struggled when some students resisted participating in advisory groups, one of their key methods of building relationships.

“If you don’t have systems like restorative justice in place, you can’t even try to fix some of these problems,” Onishi said.

“It feels like it’s not working,” she added. But the breakdown in school climate this year without it “proves how essential it is.”

‘They’re just quieter’

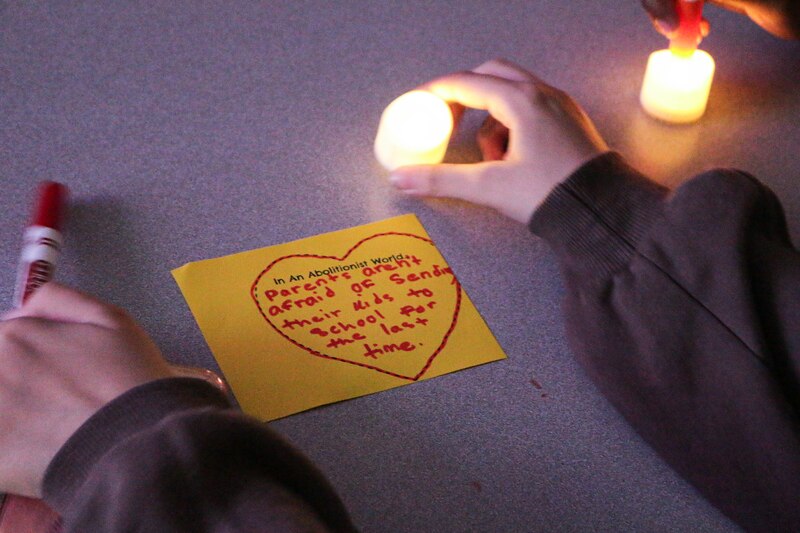

On a recent morning, a group of ninth graders at Harvest Collegiate High School filed into a room outfitted with pink and blue bean bag chairs, a couch, and a circular table. One by one, they shared their feelings about soon-to-be-released report cards, passing around a stuffed yellow fabric donut to indicate when it was a student’s turn to talk.

Some students reported feelings of anxiety, with one girl saying she hoped to hide the results from her parents. Another student chimed in that he was “not as stressed because I made a lot of progress since last year” — a comment that drew snaps of approval from many of the 18 other assembled students. Students were later paired with classmates who had large numbers of missing assignments to help figure out which ones to prioritize.

These “circle” conversations — which the school held more than 200 times this year — represent one of the strategies to help students build relationships with each other and feel connected to the school.

At Harvest, this year’s biggest struggle wasn’t fighting. The more pervasive issue: Students were withdrawn, glued to their phones or wandering the hallways instead of heading to class.

“Students are talking to each other less — they’re just quieter, period,” said Kate Burch, the school’s principal. “Their little bodies have just absorbed so much fear.”

Finding the ability to concentrate again in the classroom has been hard after spending much of the past two years at home, said Amber Colon, a 10th grader student who co-led the restorative circle conversation about report cards. She’s not surprised that students are spending more time on their phones during class this year.

“Not that many people were socializing over Zoom — you were just staring at a phone the whole time,” Colon said. “When I sit down for so long, I get really antsy. With Zoom, I could walk around my house.”

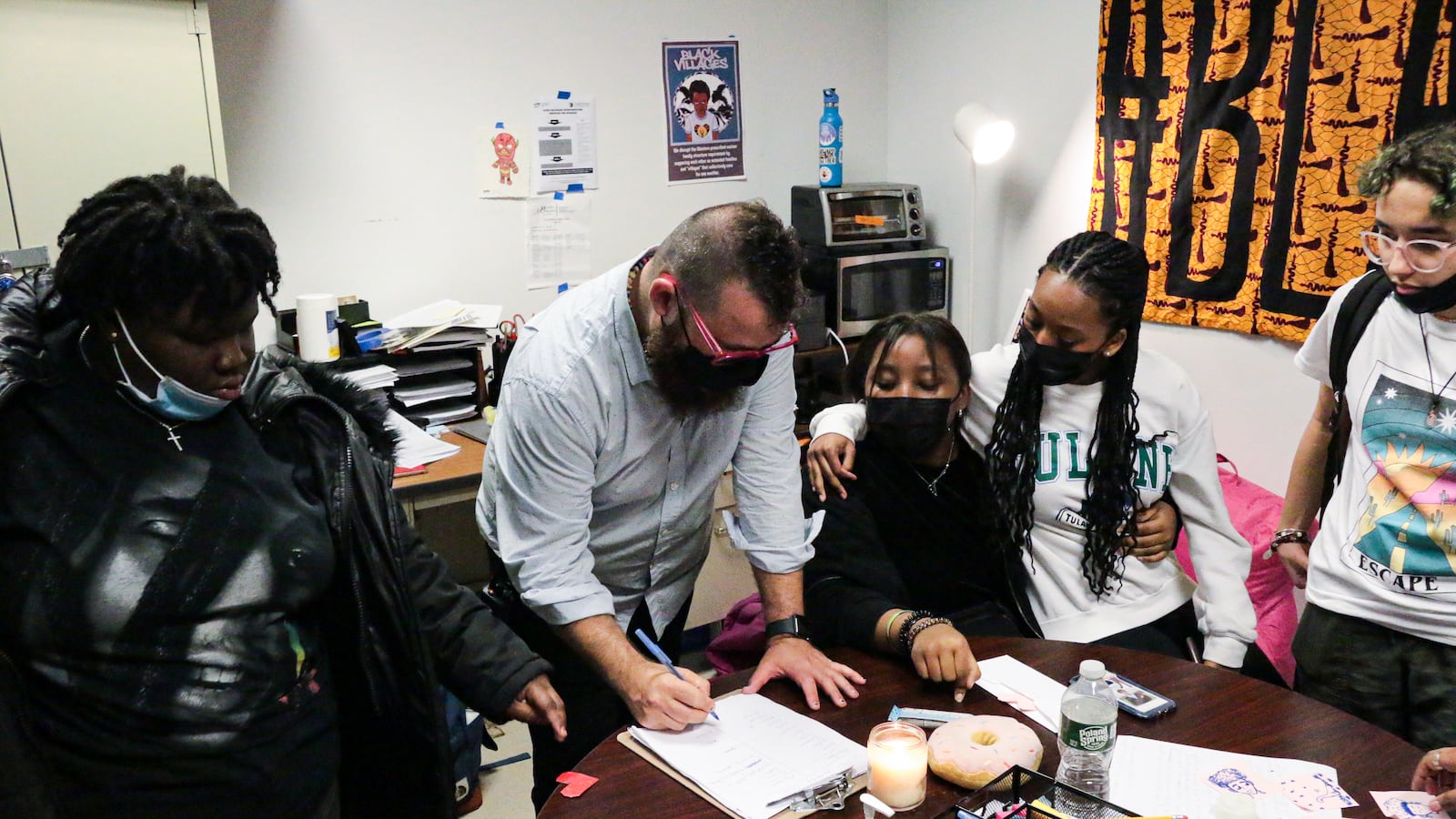

Urbach, the school’s restorative justice coordinator, is working on several of these fronts at once. A former music teacher at Harvest, this year was his first focusing almost exclusively on restorative justice work. The school’s previous restorative justice coordinator died of COVID in 2020 after a year-long medical leave.

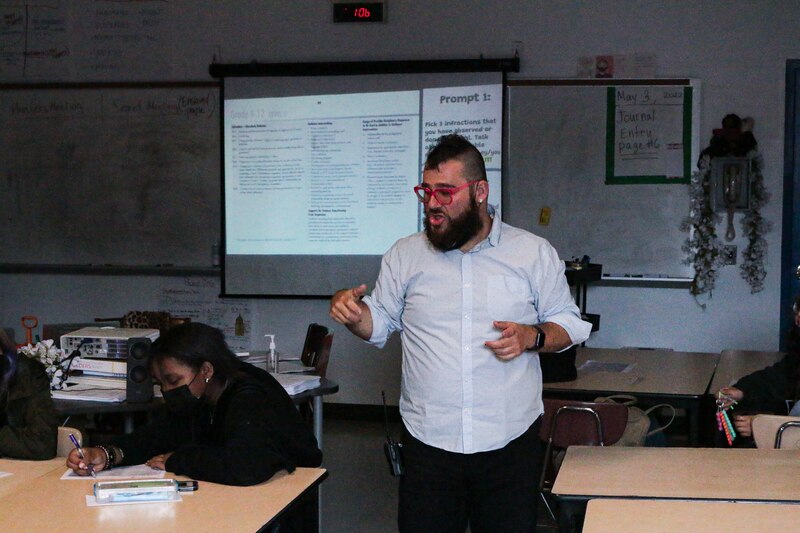

Urbach’s days this year were often a whirlwind, arranging mediations, pairing students with similar interests to spark friendships, or even dispensing instant noodles to students who don’t like the cafeteria food. He also teaches a separate class focused on restorative justice principles.

But even at a school committed to it, restorative justice can be hard to balance with other needs. Working out a conflict between a group of students can require hours of circles held over weeks or months. Because time during the school day is limited, students often miss class to participate in them, a greater challenge after three consecutive school years of intense academic disruption. At the same time, staff are burned out, stretched thin, and “everybody’s stamina for conflict resolution is just lower,” Urbach said.

On a recent afternoon, Urbach shuttled from classroom to classroom to assemble a restorative circle for the group of ninth grade boys who struggled with immature behaviors this year. One teacher was more than willing to send the student out because he was being disruptive that day. But when Urbach poked his head into a different classroom looking for another student, the teacher waved Urbach away because the student had missed too many classes this year.

“That’s a tension, and that’s a tension that’s not going away,” Urbach said, adding that he tries not to pull students out of classes they’re struggling in and often holds circles during lunch or other free periods to be less disruptive.

The research on how restorative justice affects student learning is limited. A randomized study from Pittsburgh found that while the effort accelerated a decline in suspensions, it also led to a decline in math scores, particularly among Black students. The study couldn’t prove what led to the decline in scores, and there are likely several contributing factors. One possibility is that restorative justice diverts some time that would otherwise be spent on academics.

Urbach sees the school’s approach to restorative justice as a key part of making students want to come to school, especially as rates of chronic absenteeism are on track to rise citywide. He was also more accommodating than usual of students who resisted going to class, a big challenge this year.

In one recent example, Urbach allowed a student suffering from depression — and whose mother was fine with her staying home — to camp out in his office. The student, one of the school’s strongest academically, was asking for advice about whether she should transfer elsewhere. He worried forcing her to go to class would prompt her to not show up to school at all.

“I 100% will keep a young person inside the school under adult supervision rather than watching Netflix” at home, he said.

Urbach acknowledged that the school’s approach to students who resist going to class is a work in progress, an issue staff are talking about how to address next school year. They’re also considering how to keep students off their phones during the day, as there is no consistent policy.

But he also pointed to the small everyday ways the school can make students feel valued.

On a recent afternoon, a student lugged a Playstation to school and surreptitiously hooked it up to a smartboard during lunch. Even though the school already has an after-school Nintendo club, Urbach’s solution was to find someone to supervise the lunch video game session rather than telling the student to stop.

“I think sometimes that’s all students want,” Urbach said.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.