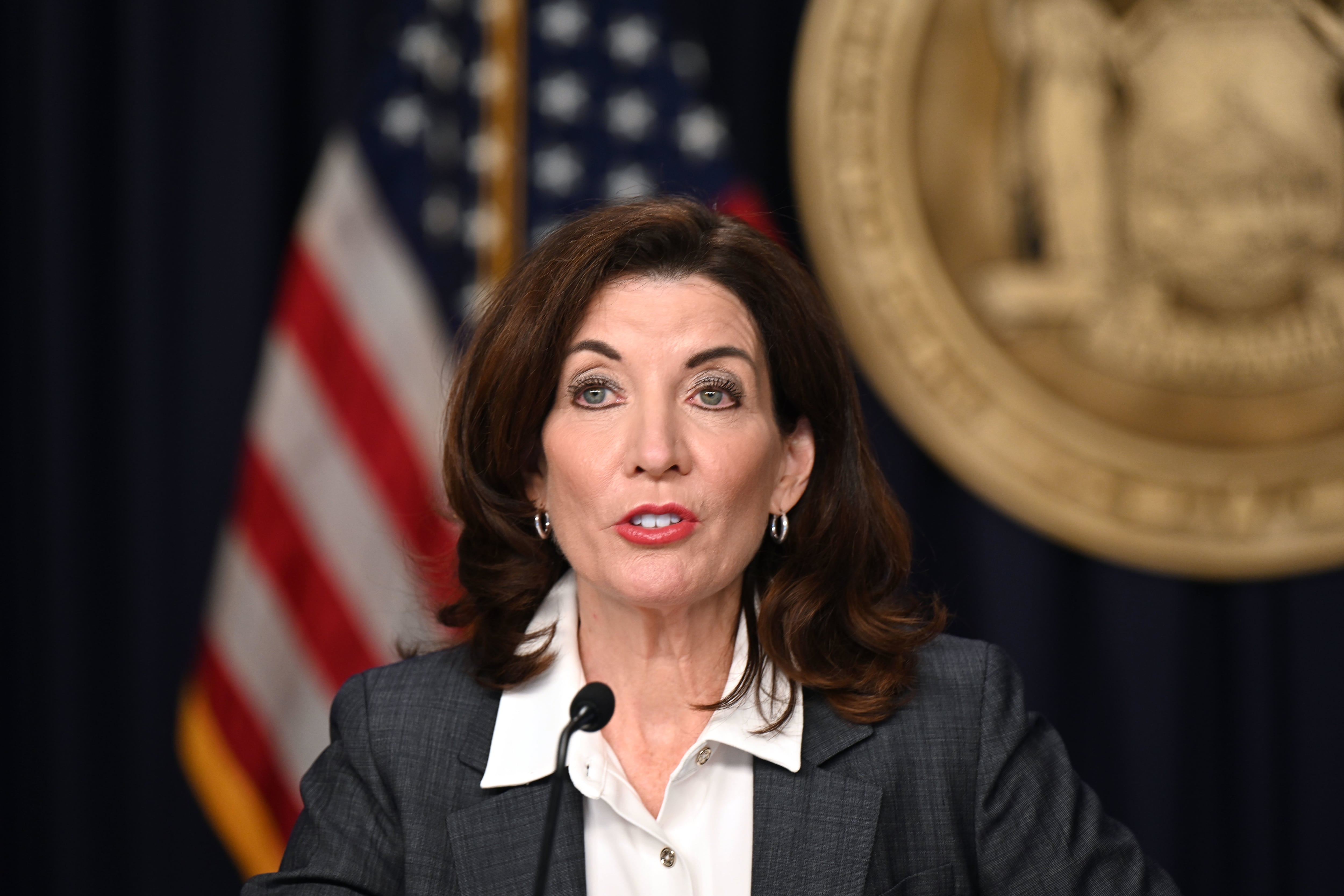

Gov. Kathy Hochul signed a bill late Thursday that extends mayoral control of New York City schools for the next two years.

But her signature came with a tweak: The eight-member expansion of the city’s education panel, which was passed under the original bill, will be delayed by five months.

Mayoral control — which allows the mayor to choose the schools chancellor and appoint a majority of members to the city’s education panel — was set to expire at midnight Friday.

The bill, passed by New York lawmakers on June 3, needed the governor’s signature to become law. Legislators typically allow the governor’s office to request bills for her review as she has hundreds to consider and sign. But Hochul did not call up the mayoral control legislation until about 9:20 p.m. Thursday.

Hochul’s office has declined to say why she waited to sign the bill or whether Mayor Eric Adams was lobbying for changes, saying only in statements this month that she has “consistently supported mayoral control.”

On Thursday evening, Queens Democratic Sen. John Liu, a chief sponsor of the bill, said he was negotiating changes with Hochul. She ultimately signed it with an agreement with lawmakers to delay the expansion of the Panel for Educational Policy, or PEP — a largely mayor-appointed board that approves major contracts and policy decisions, such as school closures and the city’s school funding formula. Originally scheduled to expand from 15 members to 23 starting Aug. 15, the expansion and first-ever term limits for panel members will now be pushed to January 15, 2023.

Lawmakers will vote in January, at the start of their next session, to adopt those changes, which is a routine time for voting on amendments to bills they’ve already passed, said Soojin Choi, a spokesperson for Liu.

The change to the bill was to “ensure that the City has sufficient time” to establish the larger PEP, Hochul wrote in her letter approving the bill. It gives appointers of panel members — most notably, Adams — five more months to make their choices. Adams failed to appoint all nine of his current appointees on time, with one forced to resign, resulting in the city failing to gain enough votes on some policy proposals.

Adams, who endorsed Hochul in the Democratic gubernatorial primary, and schools Chancellor David Banks both expressed disappointment about the bill when it passed earlier this month. It extended mayoral control for half of the time that Adams and Hochul had called for, and it added provisions meant to water down Adams’ control over the Panel for Educational Policy.

Legislators passed the mayoral control bill earlier this month as part of a package deal with a separate bill that would force the city to lower class sizes across all grades. The class size bill passed nearly unanimously, but city officials and a budget watchdog have raised concerns that it’s going to be too costly to implement.

Hochul still hasn’t requested the class-size bill, angering some lawmakers, advocates and the city’s teachers union.

“We are calling on the governor to sign this legislation now,” Michael Mulgrew, president of the teachers union, said in a statement Friday morning. “Our students can’t wait.”

Asked whether Adams was lobbying the governor for changes to either bill, City Hall spokesperson Amaris Cockfield said they do not comment on “private conversations.” In a statement Friday morning, Adams thanked Hochul for signing off on mayoral control.

Had the bill remained unsigned, the city would have had to reconstitute the previous system of 32 community school boards, plus a citywide board of education, made up of members appointed by each of the five borough presidents and two by the mayor’s office.

But it’s unclear that much would have changed in the immediate aftermath. When mayoral control lapsed for a month under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the reconstituted board voted to appoint then-Chancellor Joel Klein.

Here’s how mayoral control will change in New York:

- The mayor’s powers will be extended through June 30, 2024.

- The PEP will grow from 15 to 23 members.

- The mayor will still appoint a majority of the PEP, with 13 picks starting Jan. 15, 2023, four more than he currently chooses. Each borough president will each continue to appoint one member. The presidents of the city’s 32 Community Education Councils, or CECS, which represent each local school district and can shape school zone boundaries, will elect five members – four more than currently – who each must represent a different borough.

- Four of the mayor’s appointees must be parents of a child attending city public schools, up from two currently. They must include at least one with a child with disabilities, one with a child in a bilingual or English as a second language program, and one with a child enrolled in District 75, which serves students with the most significant disabilities.

- Each PEP member will serve a one-year term that can be renewed annually. The mayor and the borough presidents can no longer remove PEP members for voting against their wishes. Previously, appointers did not have to share a reason for why they wanted to remove someone.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.