The education department can move forward with budget cuts after an appeals court temporarily blocked a lower court’s ruling that invalidated the budget process.

The appellate court’s order Tuesday brings whiplash to back-to-school planning for the fall. Four days prior, a lower court judge ruled that the city needed to redo the education department budget, which includes cuts for nearly 75% of schools. Now that order has been paused — at least until the case is back in court on Aug. 29, a little more than a week before the first day of school.

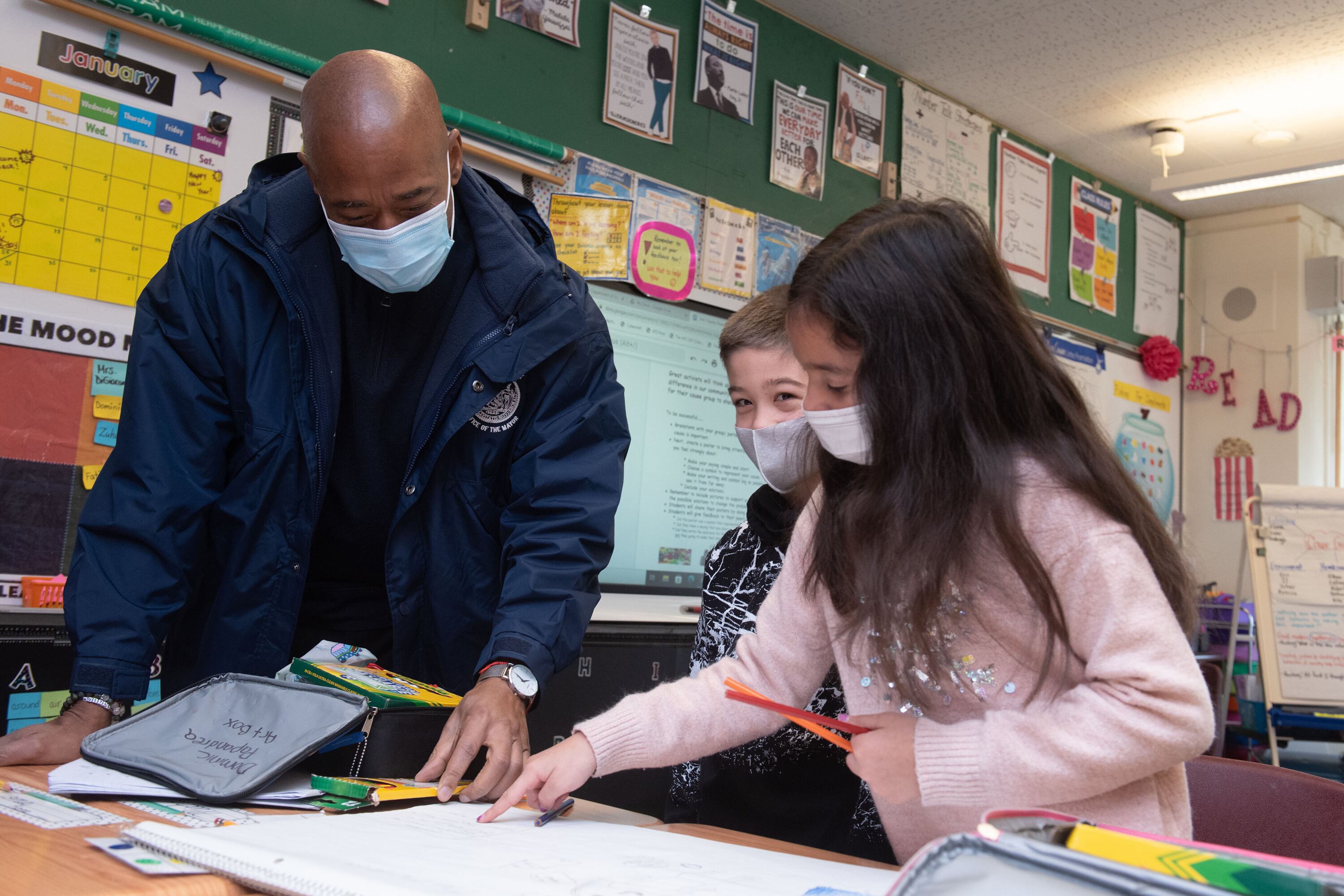

A spokesperson for Mayor Eric Adams applauded the decision allowing the city to move forward with its current budget.

“As Mayor Adams said this morning, schools will open, on time, in September and will have the resources they need to ensure our students thrive next month,” City Hall spokesperson Amaris Cockfield said in a statement. “We will continue to defend the city’s budget process.”

The Aug. 5 ruling in favor of two teachers and two parents who filed a lawsuit in Manhattan Supreme Court last month said that the city violated state law when it approved the education department’s budget for this fiscal year.

The ruling called on Adams and the City Council to reconsider how to fund schools this year, and until that happens, it meant the school system should be funded at the same levels as last year. Last year’s budget was about $1 billion more than this fiscal year’s $31 billion budget, largely due to a boost from federal stimulus relief.

The city and the education department filed their appeal earlier on Tuesday claiming that the Aug. 5 decision by Manhattan Supreme Court Judge Lyle Frank “plunges [the education department] into chaos at the worst possible time and causes irreparable harm,” and “throws a wrench” into planning for September “that may reverberate throughout the school year.”

The appeal not only pushes back on the lower court’s finding that a procedural error was made, it also said it was an “entirely unprecedented remedy of imposing a record-high and expired budget on DOE.” City lawyers argued that the lower court’s ruling could require the education department to spend “at levels that would likely exhaust the funding allocated to it well before the end of the school year.”

Laura Barbieri, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, emphasized that the appeals court issued an “automatic stay” and had not yet ruled on the substance of the case.

“We are disappointed that the city asked for a hearing date at the end of August, rather than immediately,” Barbieri wrote in a statement posted on Twitter.

“This will further delay the ‘chaos’ that the city repeatedly cited in its brief, and prevent principals, teachers, and parents from knowing what their school budgets will look like until the appeal is heard on August 29.” The automatic stay “is not appealable,” Barbieri wrote in a text message.

For now, the legal back-and-forth does not appear to have caused any dramatic changes in school operations, aside from a very short freeze on school spending that was quickly lifted. Still, the sudden reversals about whether the city can move forward with cuts threatens to sow uncertainty about school budgets less than a month before the first day of school.

The lawsuit focuses on the budget approval process, with the lower court finding that schools Chancellor David Banks had violated the law by using an “emergency declaration” to circumvent a vote on it by the Panel for Educational Policy, a largely mayoral appointed board that approves spending and contracts.

But the larger issue that touched off the lawsuit was Adams’ $215 million cuts to schools. That number has been a moving target. The cuts were closer to $373 million, according to City Council and city Comptroller Brad Lander, who has said the city has enough stimulus funding leftover from last year to cover the cuts.

City Hall argues that school budgets need to be reduced to account for enrollment declines that have accelerated during the pandemic. The previous administration used federal funding to keep school budgets steady even if they lost students and the administration contends that cuts are necessary to avoid even steeper cuts in two years when federal funding runs dry.

But many parents, advocates, and educators counter that the stimulus funding was designed to avert further disruptions to learning and that it doesn’t make sense to kneecap schools at a time when children have deep academic and emotional scars.

It’s possible that the city will ultimately restore some school funding even if officials are not forced to do so by the courts. City Hall has reportedly been negotiating with the City Council over restoring funding, but those talks have not yielded a deal.

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.