Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get the latest news on NYC’s public schools.

New York City has revised its training for educators on when to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect in an effort to cut down on unwarranted investigations that disproportionately target Black and Latino families, officials said Thursday.

Educators are “mandated reporters” under state law, and, for years, the prevailing message in their training was to err on the side of caution by reporting whenever in doubt, officials said.

But that guidance has led to an overreliance on child welfare reports, officials argued, prompting thousands of investigations each year. Few of those investigations lead to confirmed findings of maltreatment, while dragging families — mostly Black and Latino — through a process that can be invasive and traumatic, officials said.

The revised training, which has already reached thousands of Education Department staffers, is an effort to get educators to think twice before defaulting to a child welfare report, and give them a set of alternatives to try first, officials said.

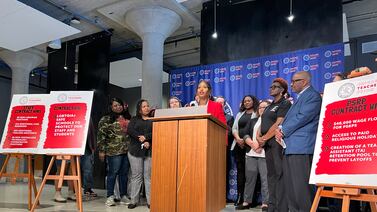

“Today our new mantra is you do not have to report a family to support a family,” said Gail Geohagen-Pratt, deputy commissioner in the state’s Office of Children and Family Services at a press conference Thursday at Education Department headquarters in Manhattan.

The city’s Administration for Children’s Services looked into a total of 59,000 reports of suspected child abuse and neglect last year, and found maltreatment in 25% of those cases, said commissioner Jess Dannhauser.

About 12,000 of those reports came from school personnel, and they yielded an even lower rate of findings of maltreatment, at 16%, a spokesperson said.

Black and Latino families were far more likely to get ensnared in child welfare investigations, with Black families reported at seven times the rate as white families, and Latino families reported four times as often, Dannhauser said.

Too often, he added, families are subjected to child welfare investigations simply for being poor.

“If a family just needs help, such as access to child care assistance, mental health counseling, or concrete resources … there are ways to provide that support without making a call that will lead to a child welfare investigation,” he said.

The new training for educators has rolled out on several fronts.

First, the state’s Office of Children and Family Services, which runs training for all mandated reporters, updated its baseline training to include sections on how mandated reporters can be swayed by implicit bias, and the potential harms of child welfare investigations for families.

The training includes a “decision-making tree” to help educators work through their options when they suspect abuse or neglect.

Dannhauser pointed to the example of a child who comes into school with poor hygiene — noting that the new training would encourage educators to look into whether the parent is providing a “minimum level of care” and ensuring they have access to resources such as running water and a washing machine before considering a call to child welfare authorities.

Similarly, a more in-depth training from the city’s Education Department and Administration for Children’s Services for the designated mandated reporting liaison at each school emphasizes the importance of relying on objective facts over subjective impressions, and offer a refresher on the resources available to schools before they turn to a child welfare report.

Dr. Jessica Chock-Goldman, a school social worker at Bard Early College High School in Manhattan and a professor at New York University, has long had concerns about the role of mandated reporters in schools – and is a member of a group called “Mandated Reporters Against Mandated Reporting.” But she was impressed by the city’s new training.

“They did a beautiful job on this,” she said. “It seems like the movement they started is about how to do these other interventions … to make ACS the last call rather than the first call.”

City officials also introduced a “prevention support hotline” at the Administration of Children’s Services that educators can call for help getting resources to families in need.

Dannhauser acknowledged that the city and state are still bound by laws governing mandated reporting that were written in the 1960s and ‘70s.

“There are a lot of calls for reform … and we think a full-scale look at that would be appropriate,” he said. Dannhauser said he’s not aware of any mandated reporters being prosecuted for failing to lodge a report of suspected maltreatment, but acknowledged it’s still a fear for some.

Changing the practice of mandated reporting in schools could also take a cultural shift that goes beyond training.

“It’s changing but it’s a slow change,” said Chock-Goldman, the school social worker, who suggested that all principals should also get in-depth training on mandated reporting.

Some advocates and parents have urged the state to scrap mandated reporting altogether, and forego the federal funding that comes with it.

But state officials were clear that they still see a role for mandated reporting.

“I wish we lived in a world where we did not have to have this because children are not being abused or maltreated,” said Geohagen-Pratt. “But we know that we are, so we have to have a mechanism in place to be able to respond to that.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.