Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get the latest news on NYC’s public schools.

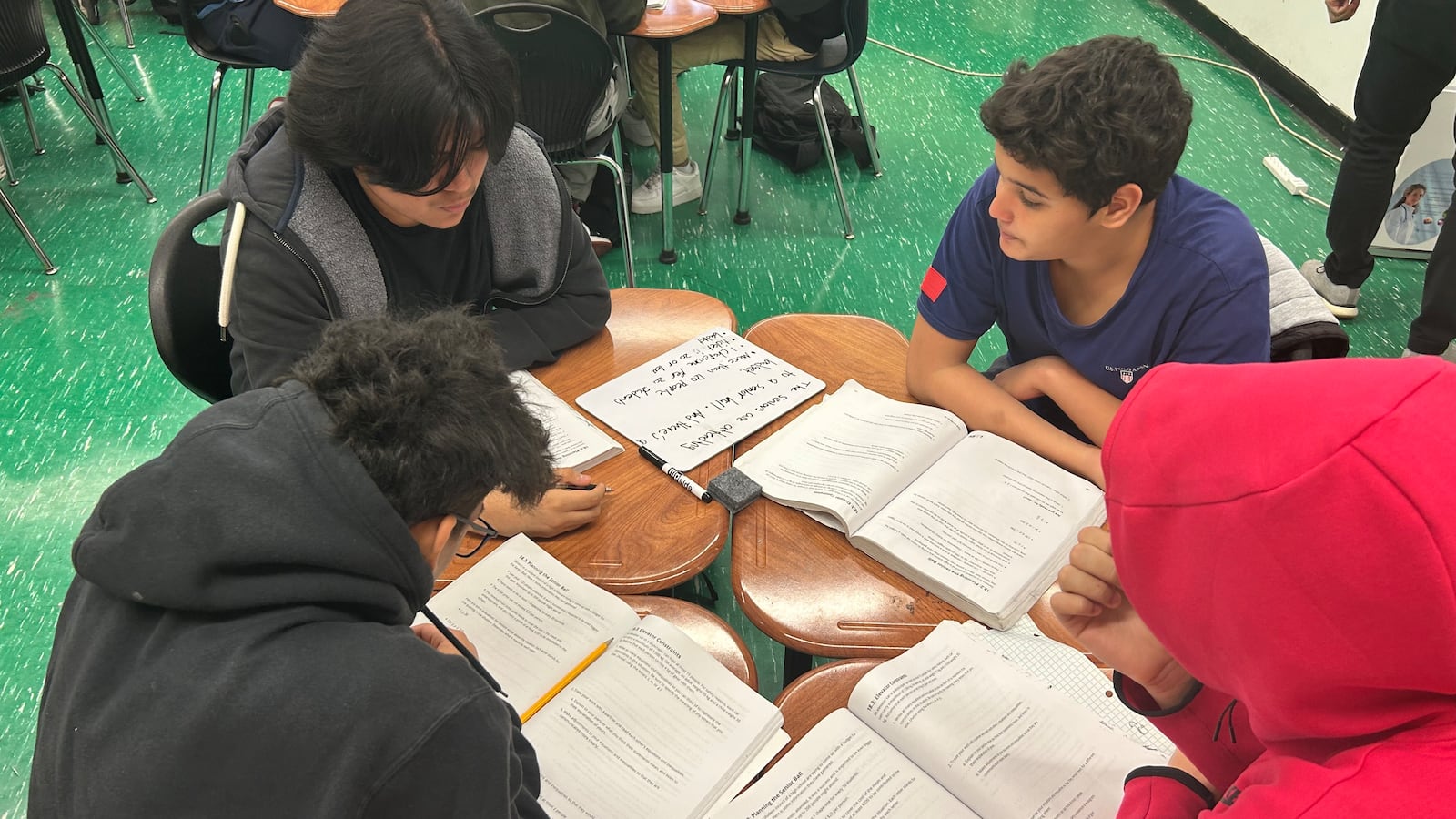

The ninth graders in Katie Carson’s Algebra I class had only a foggy memory of how to use the “greater than” and “less than” signs that appeared in their warm-up exercise on a recent Tuesday afternoon.

One student said he hadn’t seen the symbols since elementary school.

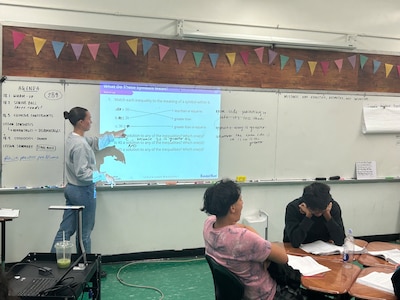

Carson, a teacher at Energy Tech High School in Long Island City, Queens, gave her class no explanation. Instead, she asked students what they noticed about how the signs work.

“If the open side is pointing to the left, it’s less than, and if it’s to the right it’s greater,” volunteered a student named Adam.

The answer wasn’t right, but Carson gamely copied it onto the whiteboard and began testing it on sample problems. A minute later, Adam interjected. “It doesn’t work. I think it’s whatever the open side is on, that’s greater.”

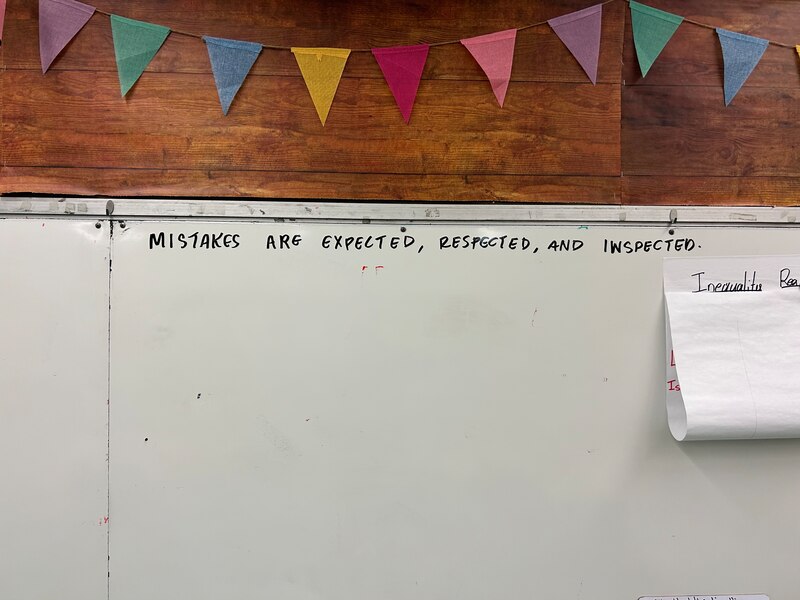

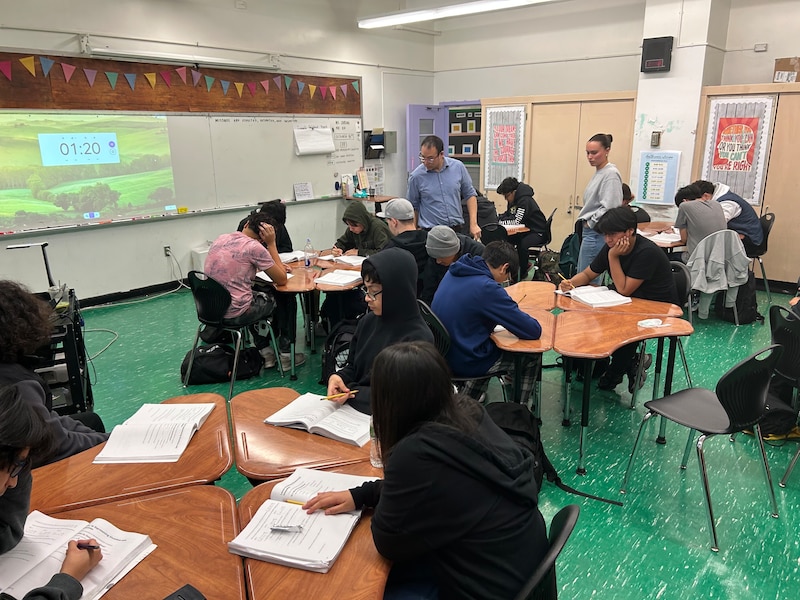

Dropping students into unfamiliar math problems with minimal introduction and refraining from correcting their errors can seem counterintuitive in a subject where the answers are black and white. But those practices are at the core of an approach that Carson says has transformed her teaching. It’s one that New York City officials are hoping can spark a sea change in how math is taught across the five boroughs.

Carson’s school was an early adopter of Illustrative Math, the curriculum New York City officials began rolling out this year as part of an unprecedented effort to improve and standardize the way algebra is taught across the city’s more-than-400 high schools.

This year, more than 260 schools are using Illustrative Math for Algebra I, while receiving extra coaching, professional development, and supervision from the Education Department. The Algebra I curriculum mandate is set to expand next year, though a department official didn’t say whether it will reach all high schools by then.

The stakes are high: Fewer than half of the city’s elementary and middle school students scored proficient on state math exams this year.

The pandemic has only heightened the challenge. Passage rates for high-schoolers on the year-end Algebra II Regents exam, which builds on Algebra I, fell a whopping 24 percentage points over the course of the pandemic, from 69% in 2019 to 45% in 2022, according to state data.

There are also gaping disparities in math achievement between schools: At some selective high schools, 100% of students who took the Algebra I Regents exam last year passed. At others, where almost all students are Black or Latino and low-income, zero did, city data shows.

Two months in, the experiment in shared curriculum has divided educators. Some argue it’s a long-overdue shift toward teaching that prizes deep conceptual understanding of math over rote practice and memorization. But other teachers say the curriculum lacks the kind of structure and built-in repetition that many students — particularly struggling ones — need.

“We show them something and don’t tell them anything, and it’s ‘What do you think?’ with no guidance,” said one special education math teacher in Queens participating in the pilot this year, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. “For a special education student who already needs a little more help, it makes it almost impossible, they check out, they lose interest.”

Proponents of the curriculum, especially teachers who’ve used it for multiple years, say they’ve found just the opposite: The curriculum’s open-endedness can help draw in even the most resistant students.

“You typically have students who walk into a math class and have heard … that they’re either a math person or they’re not,” Carson said. “But when they walk into an [Illustrative Math] class, the curriculum doesn’t care if you’re ‘good at math…’ it just makes you explain and prove and share and discuss in a way that it’s going to be challenging for everyone.”

To standardize or not to standardize?

Schools Chancellor David Banks has bet big on the idea that standardizing curriculum can move the academic needle citywide in a system where that’s notoriously hard to do.

Alongside the math push, he’s requiring the city’s elementary school superintendents to choose among three pre-selected reading curricula that officials say better align with a growing body of research about how kids learn to read. The literacy push has gotten significantly more attention, but educators say the math initiative is no less important – or controversial.

Traditionally, high schools and secondary math educators have had wide latitude to select or create their curriculum. For some teachers, especially experienced ones, that freedom can be helpful and spark innovation. Banks, however, argues that as a citywide policy, curricular autonomy has produced mediocre and inequitable results.

“Everybody is not ready for that level of autonomy,” he recently told reporters. “Because if they were, we would have much better results than we have.”

Why Algebra I?

Banks’s curriculum mandate isn’t the first time city officials have tried to boost math achievement by targeting algebra.

An initiative called “Algebra For All” under former Mayor Bill de Blasio attempted to give every student a chance to complete Algebra I by the end of eighth grade – a goal that has become a flashpoint in national debates about equity and math instruction.

That experiment yielded some positive results: In 2023, about 45% of the city’s 62,000 eighth graders took the Algebra I Regents exam, according to the Education Department – up from 30% in 2015. About three-quarters of them passed.

But disparities remain: A higher proportion of white and Asian American students took the test in eighth grade than Black and Latino students, and they were far more likely to pass it, according to a Chalkbeat review of 2022 Algebra I Regents results in more than 200 middle schools.

For the remaining students who either never took the course in eighth grade or flunked the exam, finishing it in ninth grade is critical, educators argue.

Without that, there’s little chance students will be able to advance to higher-level math courses like precalculus or calculus.

Teachers of high school Algebra I say there are significant obstacles to that goal, including a large number of students who are far behind grade level.

In many cases, teachers feel pressure to return to what feel like safer approaches, like relying on rote practice and pausing grade-level instruction to focus on remediating basic skills like multiplication, multiple educators said.

Jason Ovalles, a math teacher at Chelsea Career and Technical Education High School and master teacher through the professional organization Math for America, knows that pressure well. He began his career as a middle school teacher in East New York without a set curriculum. He tried finding interesting problems and activities on his own, but was often “pulled back” into the way he was taught: “Just tell them how it’s supposed to be, so that they can copy what you did.”

Switching to Illustrative Math allowed him to keep up with grade-level math without alienating or discouraging his struggling students, Ovalles said. Proponents hope it can do the same thing citywide.

Curriculum draws mixed reactions

Illustrative Math was created in 2011 by a University of Arizona professor in the wake of sweeping changes to math teaching during the 2009 rollout of the Common Core standards, a set of benchmarks meant to give states shared academic goals.

Other large school districts, including Los Angeles, are also rolling out the curriculum at scale.

Teachers participating in New York City’s pilot get eight professional development sessions and between eight and 12 visits from an instructional coach throughout the school year, according to the Education Department.

But multiple educators said there are major flaws in the curriculum, and the Education Department’s approach to rolling it out.

Some students don’t have the necessary vocabulary or background knowledge to engage in the open-ended discussions, said one Brooklyn educator who used the curriculum last year at his administrators’ behest. He compared it to asking students in an automotive class who’ve never seen a car engine before to fix a muffler.

“All the investigative time in the world will not make them successful at making it run quietly,” said the teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

The lack of built-in practice time can make it difficult to verify whether students fully understand concepts before moving on, several educators added.

Teachers who have used the curriculum for years countered that part of what makes it work is that students don’t need vocabulary up front. They can describe concepts in their own words – a feature that’s especially helpful for English language learners – and teachers can bring in the technical terms later.

Ovalles said he’s learned that it’s okay – and expected – to move on before every student understands 100% of the lesson because the curriculum builds in future opportunities to revisit topics.

Education Department officials are holding teachers to a pacing guide, reminding teachers when they should wrap up units, according to communications reviewed by Chalkbeat.

Several educators said the pacing expectations are unrealistic and have made it harder to adjust to the new curriculum. An Education Department official said the pacing guide is “not a mandate” and teachers have freedom to spend longer on individual lessons if they need.

Regents loom large

A big question hangs over the entire experiment: Will the new curriculum improve results on the year-end Regents exams?

Multiple educators who are using the curriculum for the first time said they’re worried that it doesn’t align well with the Regents. The test is mainly multiple choice and it phrases questions in specific ways.

Energy Tech has been using Illustrative Math since 2020 as part of a pilot funded by New Visions, a network that runs and supports public schools, and the school saw its percentage of students who passed the Algebra I test rise from 64% in 2019 to 72% last year, even as citywide numbers declined, according to state data.

Kiran Purohit, the vice president of curriculum and instruction at New Visions, said overall, the schools in the pilot “saw a better post-Covid recovery” in Algebra I than the city average, with an especially big bump for English learners.

Sixteen-year-old Energy Tech student Mostafa Aboelfadl said he’s “not the best test-taker” and would often freeze up on open-response questions on the Regents. But after spending a year chipping away bit-by-bit at complex problems in his Illustrative Math algebra class, he said he realized he could “extract points” from Regents questions even if he didn’t know the full answers.

An Education Department spokesperson said the pacing guide includes some designated Regents review days and suggestions about which lessons can be “deprioritized” because they don’t appear on the exams.

It’s also likely that the Regents test itself and its role will continue to shift. The Algebra I Regents exam is changing this year to better reflect a new set of learning standards. And a Blue Ribbon commission is poised to release a set of recommendations about how and whether Regents exams should continue to serve as graduation requirements.

Ovalles said after several years of using the curriculum, he hasn’t seen much change in his students’ Regents scores – but that’s okay.

In the past, he’d spend “spend weeks and months” on Regents prep, only to see scores stay flat as well.

Now, at least, the tone seems to have shifted among students. “They’re actually understanding math better and are more confident talking about it,” he said. “It feels like a net positive.”

Alex Zimmerman contributed.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.