Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

For nearly all of her decadelong teaching career, Abby Loomis used one of the most popular reading programs in New York City, a curriculum that aimed to foster a love of literature by giving students plenty of time to independently read books of their choosing.

She found the program, developed by Teachers College professor Lucy Calkins, engaging — particularly for students who were easily absorbed by books. Still, she noticed many other children struggled to read independently, and Loomis cobbled together other resources to help them.

So, the fourth grade teacher felt open minded when the city announced in May a sweeping overhaul of elementary literacy instruction, forcing schools to abandon programs like Calkins’ in favor of those that city officials say line up with an established body of research about how children learn to read, often called the “science of reading.”

But a couple months into the city’s curriculum overhaul, Loomis and several other teachers said they haven’t yet received the training they need to make it work.

“The general sentiment at my school is we’re being asked to start something without really knowing what it should look like,” said Loomis, who asked that her Brooklyn school not be named. “I feel like I’m improvising — and not based on the science of reading.”

In nearly half of the city’s local districts this fall, elementary school teachers were required to adopt one of three curriculums alongside separate phonics lessons that explicitly teach students the relationships between sounds and letters. The remaining elementary schools will be required to use the materials next school year.

Literacy experts have largely praised the new mandate. By moving from a hodgepodge of different curriculums that varied school by school, it’s easier to train teachers at a larger scale. The city has added a pacing calendar that tells educators how quickly they should move through the materials, meaning children may face less disruption if they switch schools.

But observers also warned that getting teachers up to speed quickly with new materials would prove challenging — and that success would hinge on whether teachers felt adequately supported. The city did not give schools much lead time, announcing the overhaul less than two months before the summer break. Teachers were expected to roll out new materials when they returned in September.

Top Education Department officials have said there was little time to waste. About half the city’s students are proficient in reading on state tests — figures that fall to about 40% among Black and Latino children.

“In the best of all worlds, we would have studied this for the next three or four years,” schools Chancellor David Banks said in an interview with Chalkbeat. “We are building the plane as we are flying it because kids’ lives are actually hanging in the balance.”

Training efforts are underway

Education Department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein said the city offered training for all teachers who are using new reading curriculums.

Teachers received between two and three days of training, though teachers said the introductory sessions offered by curriculum companies were mostly broad overviews including how to access digital materials rather than deep dives on instruction.

After disbanding its in-house literacy coaching program, Education Department officials contracted with several outside companies to provide individualized coaching to educators. All teachers in the first phase should have participated in at least one coaching session so far, Brownstein said, and will receive at least eight sessions overall. The city’s teachers union also hosted two-week seminars over the summer and has over 200 coaches helping teachers with the new materials, a union spokesperson said.

“Educators are receiving ongoing supports, including 1-on-1 coaching, throughout the school year to ensure that they are comfortable with the material and able to teach it with fidelity,” Brownstein said.

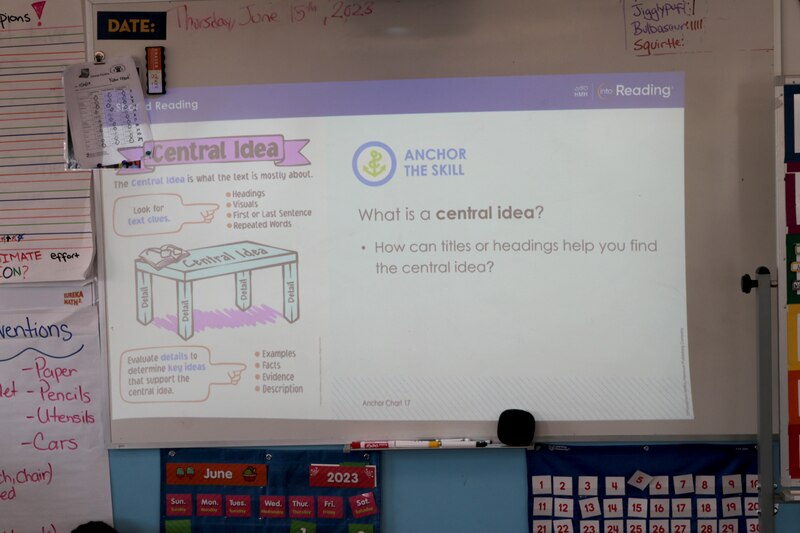

Most teachers are using a program called Into Reading from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the curriculum required by 13 of the 15 district superintendents who are part of the mandate’s first phase.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt made its sprawling set of digital materials free for city educators during the pandemic, and boasts a Spanish language version, likely contributing to its popularity. About 53% of schools in the first phase were already using Into Reading before this fall, Brownstein said.

But even as many educators weren’t starting from scratch, several teachers including Loomis — whose school began incorporating Into Reading during the pandemic — said they’ve still struggled with the densely packed lessons.

Teachers crave more hands-on help

One Brooklyn elementary school teacher said the rollout has been frustrating, noting that some teacher guides arrived late. And while she has concerns about the Into Reading curriculum, including criticism about its cultural responsiveness and emphasis on short text excerpts rather than whole books, she said the coaching has been a bright spot.

During twice-a-month meetings that last two periods, the school’s teachers are encouraged to bring their lesson plans for the next week so they can trouble-shoot with their coach, who was provided by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. “I am learning a lot,” said the teacher, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “I wish it was longer.”

Other teachers said their interaction with coaches has been limited, and crave more guidance on how to transition away from Calkins’ approach. Some schools that previously used Calkins’ materials paid for regular coaching that was popular with many teachers.

Into Reading involves longer periods of teacher-led instruction, and typically asks students to read more difficult texts at their grade level. Instead of encouraging children to read books of their choosing, they spend more time collectively reading excerpts from a textbook.

Some educators said they’re looking for help making the lessons more captivating, finding that students may not be able to sit still for 30 minutes or more of teacher-led instruction compared with the tighter 10- to 15-minute lessons in Calkins’ curriculum. Others said the program’s texts are more difficult and are looking for strategies to make them accessible, especially for English learners or students with disabilities. The curriculum is packed with resources, from vocabulary and spelling materials to writing activities, with little time to get to them all, teachers said.

Meanwhile, multiple educators said they’ve been directed to reconfigure their classroom libraries so that they’re no longer organized by reading level, a hallmark of Calkins’ approach. But it’s a time-consuming task that has frustrated some teachers who contend they received little explanation about what the goal of the reorganization is.

One veteran teacher misses elements of Calkins’ curriculum, which involved modeling a skill and then sending students off to practice on their own. She feels like the scripted lessons from Into Reading lack creativity.

“I feel like I’m not really sure how much they’re loving reading,” said the teacher, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

She’s also struggled with moments when the Into Reading curriculum assumes students have skills that haven’t been explicitly introduced yet, such as a recent writing exercise that involved apostrophes. The teacher quickly pivoted to a mini grammar lesson on the fly.

“I didn’t do it very well because I was trying to cover so many different skills in the little time I had,” she said.

A coach observed one of her lessons, but there wasn’t time for feedback. The teacher said she’s turned to Facebook groups when she has questions. Though she’s been in the classroom since the 1980s, pivoting to a new curriculum has left her feeling like a novice, spending Friday evenings poring over lesson plans for the next week.

Supporters say curriculum overhauls take time

Teachers have struggled with other elements of the reading overhaul, including a push to more consistently deploy phonics lessons.

Marnie Geltman, a third grade teacher at P.S. 150 in Queens, said she typically teaches older children where phonics lessons aren’t the norm. Geltman said that neither she nor her co-teacher have received much training on how to deliver the highly regimented lessons.

Education department officials said the city continuously provides phonics training, though Geltman said they’ve filled up quickly and she hasn’t participated yet.

“I just think it’s been too fast,” she said. “We should have been trained first.”

Others involved in the city’s literacy efforts said it is unsurprising that teachers feel overwhelmed in the initial phases of the transition.

Lynette Guastaferro, the CEO of Teaching Matters, an organization that has contracted with the city to help train teachers in three local districts, said the first year of a curriculum change is typically a big learning curve.

She stressed that changing curriculum strategies is a long-term project.

“We’re two months in,” she said. “This is about the next five years of change.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.