This story about themed schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

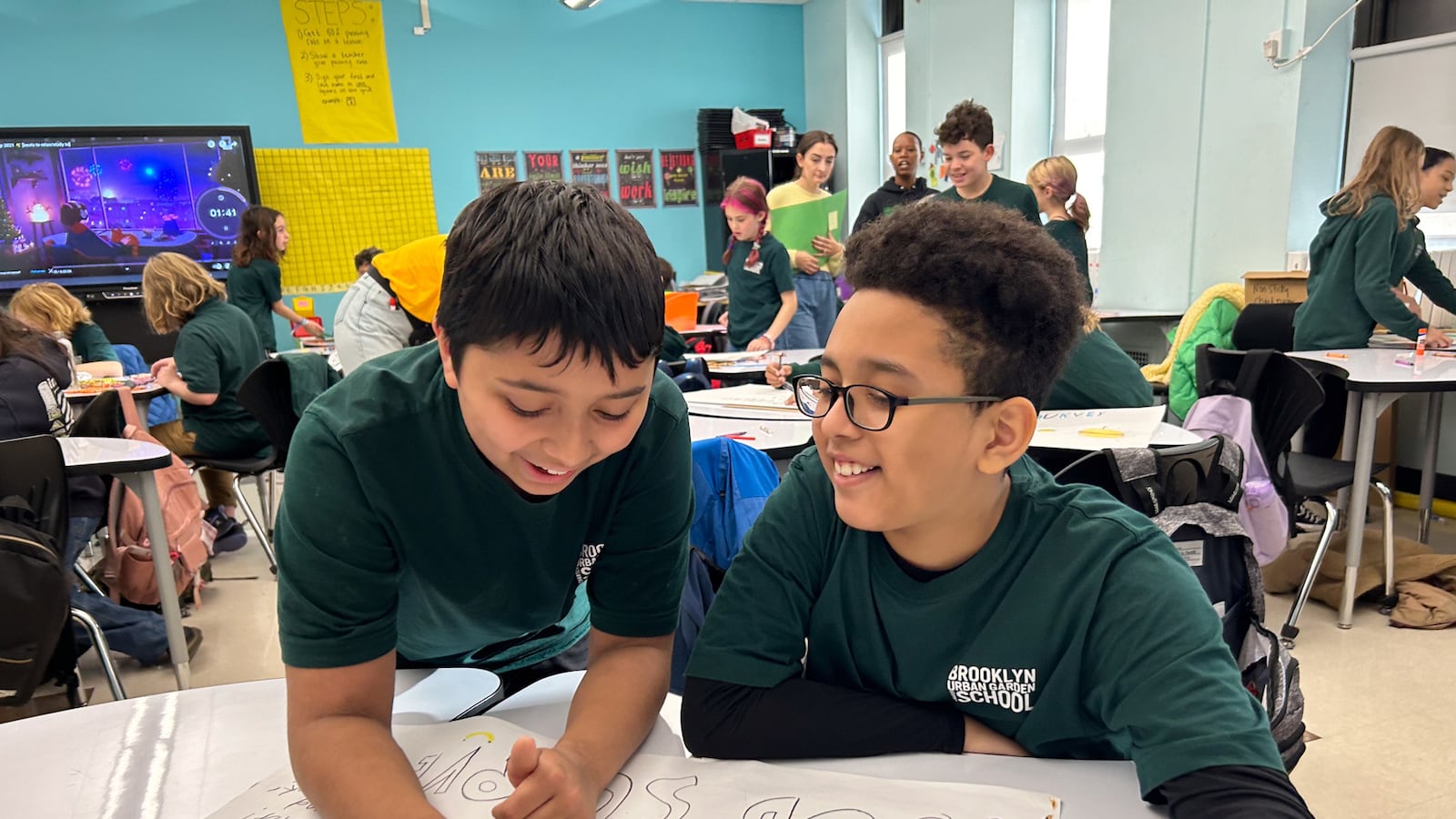

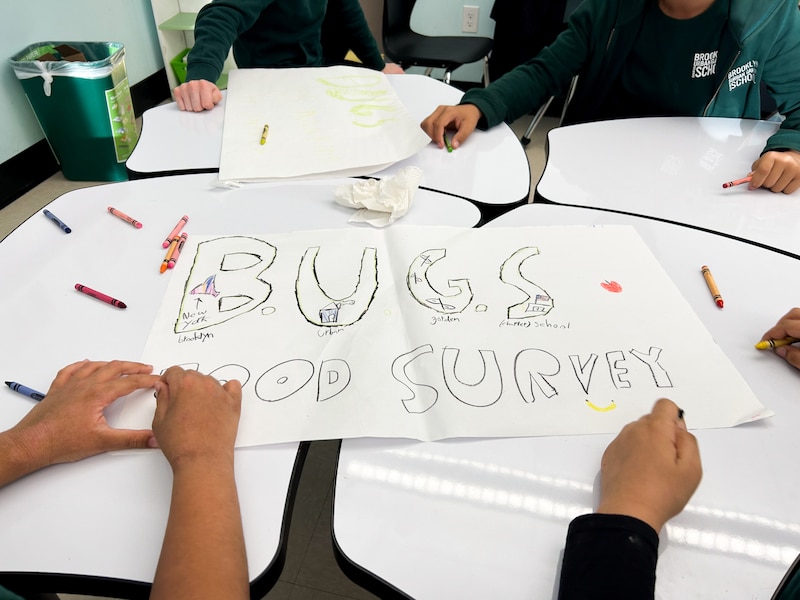

On a sunny Friday in early November, four 10- and 11-year-old boys stand on the corner of 26th Street and Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, holding homemade clipboards and signs that read “Take our food equity survey.”

A young man rushes past the group, headphones on, eyes on his phone. Susan Tenner, executive director of the Brooklyn Urban Garden Charter School, or BUGS, where the boys are sixth graders, suggests they let him pass. The next passerby is a runner — even more unpromising.

When a guy in his 20s or 30s in a puffer coat with fur trim comes along a half a minute later, Elias, a 10-year-old, remarks that he looks busy too. But Tenner urges the students to pounce.

“Everyone in New York City looks busy,” she tells them. “You guys are cute; people are going to want to help you.”

And the man does. After the boys call out as he passes, the man doubles back to take the student-made survey. Their first success.

Over the next half hour, the boys and a group of girls positioned a block up will interview a postman, a construction worker, a pair of teenage girls in fleece Snoopy pants, and several others about their access to healthy, affordable food.

BUGS, one of hundreds of “themed” middle schools spread across New York City and the nation, fully embodies the “green” school concept. There are gardens out front and hydroponic produce growing inside, an indoor tank for raising trout and recycled furniture in the classrooms. Students take a weekly sustainability class and participate in monthly field study days that send them into the community to conduct research on topics like land use, pollution and food equity.

Adopting a theme like sustainability, the arts, or math and science can cement a middle school’s culture, give coherence to its curricula, and boost student engagement at a time when many students are losing interest in school. Done well, proponents say, a theme can help students connect what they’re learning in the classroom to some larger purpose or vision of their future.

But not all themed schools are as distinctive as BUGS, and some aren’t all that different from mainstream middles. It can be hard to tell, based on a name alone, whether a self-proclaimed “green” school offers a fully integrated sustainability curriculum, or is simply located in a net zero building.

Attending a themed school offers no guarantee of success in the focus subject, either. At some STEM-themed schools in New York City, students score below the citywide average on the state standardized math test.

Meanwhile, some high-performing themed schools remain out of reach to many low-income students, due to screenings — such as tests or auditions — that favor families who can afford private lessons and tutors.

This variation in scope, access and outcomes means that students and parents need to do their research before choosing a school with a catchy name, said Joyce Szuflita, a longtime school consultant to Brooklyn families. “Buyer beware,” she advised. “Sometimes there will be a name on a school that has nothing to do with what’s happening in the building. It’s more like branding.”

Related: The path to a career could start in middle school

There’s no national count of the number of themed middle schools, which are less common than themed high schools. But they’re cropping up across the country, particularly in places where families aren’t limited to their neighborhood school zone, according to Andrew Maxey, a member of the board of trustees of the Association for Middle Level Education, or AMLE, an organization that supports middle school educators.

In cities like New York, where students can choose among public schools, public charters, and private schools, a theme can be a way for a program to stand out from the competition. It can also help convince some middle-class parents to stick with city public schools for the middle grades, instead of fleeing for private schools or the suburbs.

A theme, said Maud Abeel, a director in the education practice at the nonprofit Jobs for the Future, “is a signal to families and educators that you’re trying to make school relevant and engaging.”

It’s also a signal to business leaders, said David Adams, the CEO of the Urban Assembly, a school support organization that has opened more than 20 career-themed public middle and high schools in New York City since 1997.

When the Urban Assembly’s founder was looking for ways to get industry more involved in public education, back in the early 90s, he settled on themes as a way “to mobilize the private sector to invest in schools,” Adams said.

But there are downsides to proclaiming a specialty. Doing so can scare away parents who worry — sometimes needlessly — that their child will be pigeonholed or miss out on opportunities to explore other areas, Szuflita said. And claiming a theme creates real pressure to “live up to the moniker,” added Abeel.

“If you’re going to put it in your name, you have to show why it’s there,” she said.

In New York City, where there are schools with straightforward names (the Middle School for Art and Philosophy), schools with clever or cute nicknames (BUGS), and schools that combine concepts in head-scratching ways (the Collegiate Academy for Mathematics and Personal Awareness), that “why” is more obvious in some cases than others.

On one end of the spectrum are schools like Ballet Tech, where middle schoolers dance five days a week, and Harbor Middle, where students pursue projects like boat-building and oyster reef monitoring.

On the other are schools that no longer fit their names, due to mission drift, leadership turnover or curricular change. A prime example is Brooklyn’s Math & Science Exploratory School, where leaders have asked the Department of Education for permission to drop the “Math & Science” from the name because “the curriculum has evolved” and the current name is “limiting and misaligned with the school’s value and goals,” according to a resolution in support of the change.

In between are dozens of schools that are implementing their themes in different ways and to varying degrees. Some, like the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women, offer an additional period or two in the theme, along with extras, like hydroponics and coding.

Others focus their electives on the theme. At New Voices, in Brooklyn, students sample six arts forms in sixth grade, then pick a major for the last two years. But parents whose children attended the school said the arts theme isn’t infused into the core subjects.

Broadly speaking, themed middle schools set aside less time for their target subject than their high school counterparts. That’s mostly because the school day is “too full to pile things on,” said Maxey, who, in addition to his work as a board member for AMLE, is director of strategic initiatives at Tuscaloosa City Schools, where there is a performing arts middle school.

Maxey said the most successful schools take an integrative, rather than an additive approach, weaving the theme across all subjects.

“You don’t carve out time for the arts,” he said. “You make them the essence of the school.”

Related: Middle school’s moment: What the science tells us about improving the middle grades

The research on the effectiveness of themed schools is thin; experts on middle school teaching say they aren’t aware of any rigorous studies comparing themed and mainstream middles.

But a pair of studies by the Research Alliance for New York City Schools — one on turnaround middle schools and another on small high schools — suggest that themes can lend cohesion to the curriculum and facilitate collaboration across disciplines, said Cheri Fancsali, the Alliance’s executive director. They can attract students, as well as teachers, to a school.

Yet the studies also showed that themes sometimes lead to a narrowing of the curriculum and alienate students who aren’t interested in the theme, Fancsali said.

Nancy Deutsch, a professor of education at the University of Virginia and an editor of the Journal of Adolescent Research, said she has mixed feelings about themed middles.

On the one hand, Deutsch said, letting students select schools that align with their interests might prevent some of the drop-off in motivation and engagement that often begins in middle school. On the flip side, attending a themed school might limit students’ future options, if they can’t take courses — Algebra I, for example — that would allow them to pursue different interests in high school.

“I would want to make sure that while there may be specialization, it’s not cutting off potential pathways,” she said.

Related: A hidden divide: How NYC’s high school system separates students by gender

Equity can be a concern as well. Some themed schools admit students based on factors like test scores or grade point averages, or require them to submit a portfolio or undergo an audition. Others have moved away from such screening methods, in an effort to build more racially and socioeconomically balanced classes.

Brooklyn’s District 15, where almost half the middle schools have themes, switched to a lottery system a few years ago. The change has reduced segregation in the district’s schools, but it has also coincided with a sharp drop in test scores at some themed schools, including the Math & Science Exploratory School, which had historically drawn a disproportionate number of white and higher-income families. This has led to speculation that the move to change the school’s name was motivated by declining test scores — a charge the school has denied.

Even so, the school’s pass rate on the state math exam — 64% in 2021-22 — was still twice the citywide average for middle schools of 32% (and climbed back to 80% during the last academic year, recently released data show). Several STEM-themed schools weren’t even meeting that low bar.

BUGS, which shares a building with a District 15 public themed middle school, the Carroll Gardens School for Innovation, is required under state charter law to admit students by lottery, with preference given to students in the district. The school is fairly diverse — roughly half the students are white — and a quarter qualify for free and reduced lunch. Close to a third have disabilities.

Last year, according to data from the New York State Department of Education, two-thirds of BUGS students passed the state math exam, though pass rates were significantly lower for students with disabilities (48%), and economically disadvantaged students (32%). The citywide average for all middle schoolers was 46.3%.

Related: Can you fix middle school by getting rid of it?

When BUGS opened a little over a decade ago, its focus was squarely on environmental sustainability. But over the years, it has expanded its purview to social and economic sustainability, too, said Tenner, the executive director.

The school’s all-in embrace of the sustainability theme is fairly unusual, said Jennifer Seydel, executive director of the Green Schools National Network. The Network’s members include schools with a couple courses in environmental studies, those with after-school “green teams,” and schools with net-zero emissions, among others.

“Operating in a public school system, you can’t go as deep or be as innovative as BUGS,” she said.

Still, given the school’s name, Tenner sometimes has to correct parents’ misperception that it’s all about planting and harvesting.

“The garden is a great outdoor classroom, but it’s only one of many in the city,” she tells families.

Their confusion may not matter much, anyway. In interviews, parents whose children attend or attended themed middle schools in Brooklyn said they made their choice for a variety of reasons, often unrelated to the theme: a school’s location, academic reputation or small size.

Parents whose kids attended the Math & Science Exploratory School said it was an open secret among affluent families living near the school that the emphasis was on exploration, and not on math and science. They wondered whether families from poorer parts of the district, whose children now make up a large share of the school’s enrollment, would know that.

Sarah Russo, whose son is a seventh grader at BUGS, said it was the school’s co-teaching approach and nurturing environment that sold her. Her son has an Individualized Education Program (a plan for students with disabilities), and she worried he’d get lost in a big, competitive school.

The BUGS survey-taking sixth graders, meanwhile, had other reasons to like the school. Elias was really excited about the lockers, while Sophia, whose group had interviewed passersby on a different corner, was thrilled that they’d get released for lunch. Sena picked BUGS over New Voices, the school her two best friends planned to attend, after realizing that the arts “aren’t my thing.”

Back in the classroom after completing their survey, the students get a refresher lesson on converting ratios into percentages and tally their responses. They find that roughly half of respondents have more restaurants and fast-food chains than grocery stores in their neighborhood, and 40% don’t know what food equity is. Three-quarters spend more than $50 per person on groceries each week.

Armed with these statistics, the students take action, writing letters to Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso to urge him to bring more grocery stores to Brooklyn neighborhoods and install more community fridges in the district.

In his letter, Elias asks Reynoso to tackle inflation and add lessons on food inequity to the city’s curricula.

“Please, Mr. Reynoso, we must do something!” he concludes, and adds his signature: a smiley face giving a thumbs up.