Chancellor David Banks plans to launch a “working group” of parents, school leaders, and others to share their opinions and concerns about a new state law that sets stricter limits on class size in New York City public schools.

Banks revealed the plan Wednesday while testifying during a state budget hearing focused on education. He outlined the potential financial costs facing the system in meeting the law’s requirements — an additional $1 billion — and suggested there are many New Yorkers whose concerns “were not heard on this as this law was developed” last year.

“But they’re going to hear from me, and they will absolutely be at the table alongside me as we figure out the best way to implement this,” Banks said.

The working group would have “parents, school leaders, and other interested parties,” Banks said.

Banks did not share more details about the group or what its goal would be. Nathaniel Styer, a spokesperson for the city’s education department, said, “We’ll have more to say soon.”

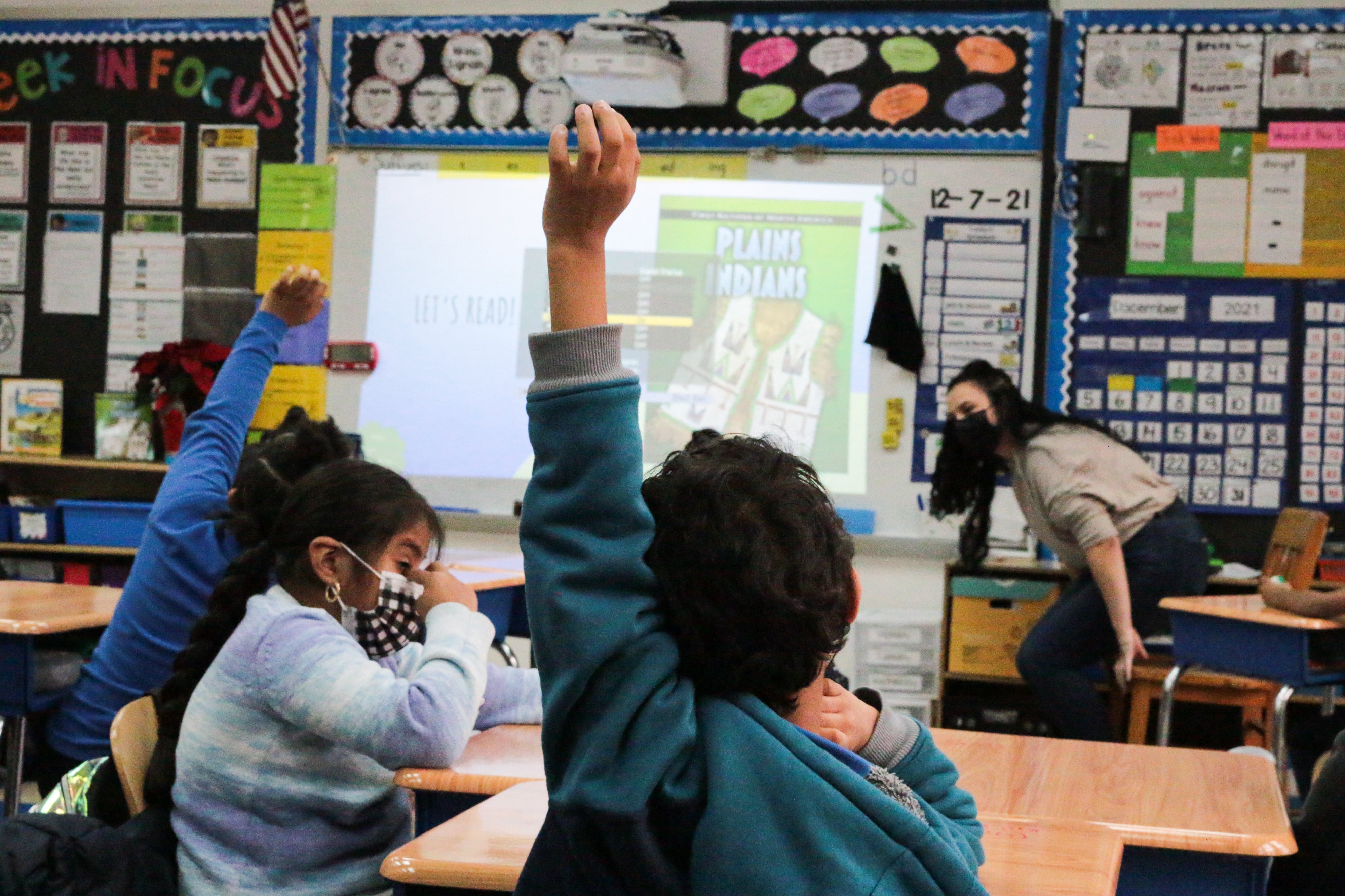

Last spring, state legislators overwhelmingly passed the class size law, which requires New York City to cap classes at 20 students in kindergarten through third grade, 23 students for grades 4-8, and 25 students for high school. The cap must not exceed 40 students for physical education and classes for “performing groups.” City schools must gradually meet these requirements by September 2028.

Officials are required to form a plan by this September, alongside the city’s educator unions. But the city’s teachers union has already criticized city officials for dragging their feet on the planning process.

In a podcast in December, union president Michael Mulgrew said he’s met with the city twice on the matter but no actual planning has started, and the city has not yet set a formal meeting to do so. (Late last month, an education department spokesperson told Chalkbeat that the city has been regularly updating the union on its progress.)

During Wednesday’s hearing, Banks said the city doesn’t anticipate any issues for meeting class size requirements during the first two years of the five-year timeline. The average class size this school year is about 24 students, according to the education department.

But Banks expects challenges later on, as class size requirements become more stringent and could lead to hard decisions, such as having to forgo hiring an art teacher because a school needs to create a new class when it’s “two students over” the limit. Budget cuts at most schools this school year led many to cut teachers, programs and services, sometimes resulting in larger class sizes.

While many schools may not have an issue meeting the requirements, other overcrowded and popular buildings may mean the city has to either limit enrollment at those schools or must build more seats.

The education department anticipates the need to hire 7,000 new teachers to comply with the law, according to Banks.

“In doing that, there are going to be other decisions that are going to have to be made by school leaders,” Banks said.

Queens Democratic Sen. John Liu, who oversees the Senate’s New York City education committee, took issue with the chancellor’s comments, emphasizing that the city should be working closely with schools in helping them comply with the state law, and that the city should be able to cover costs with the increase in Foundation Aid.

In the union podcast, class size advocate Leonie Haimson said she was pushing for a task force with parents, advocates, experts, and both teachers and principals unions to “work together toward a reasonable, rational, equitable, effective” plan.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City schools with a focus on state policy and English language learners. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.