The dire mental health conditions for staff and a wave of teacher resignations at one Brooklyn charter school prompted administrators to create a new position this year: a social worker responsible for supporting educators.

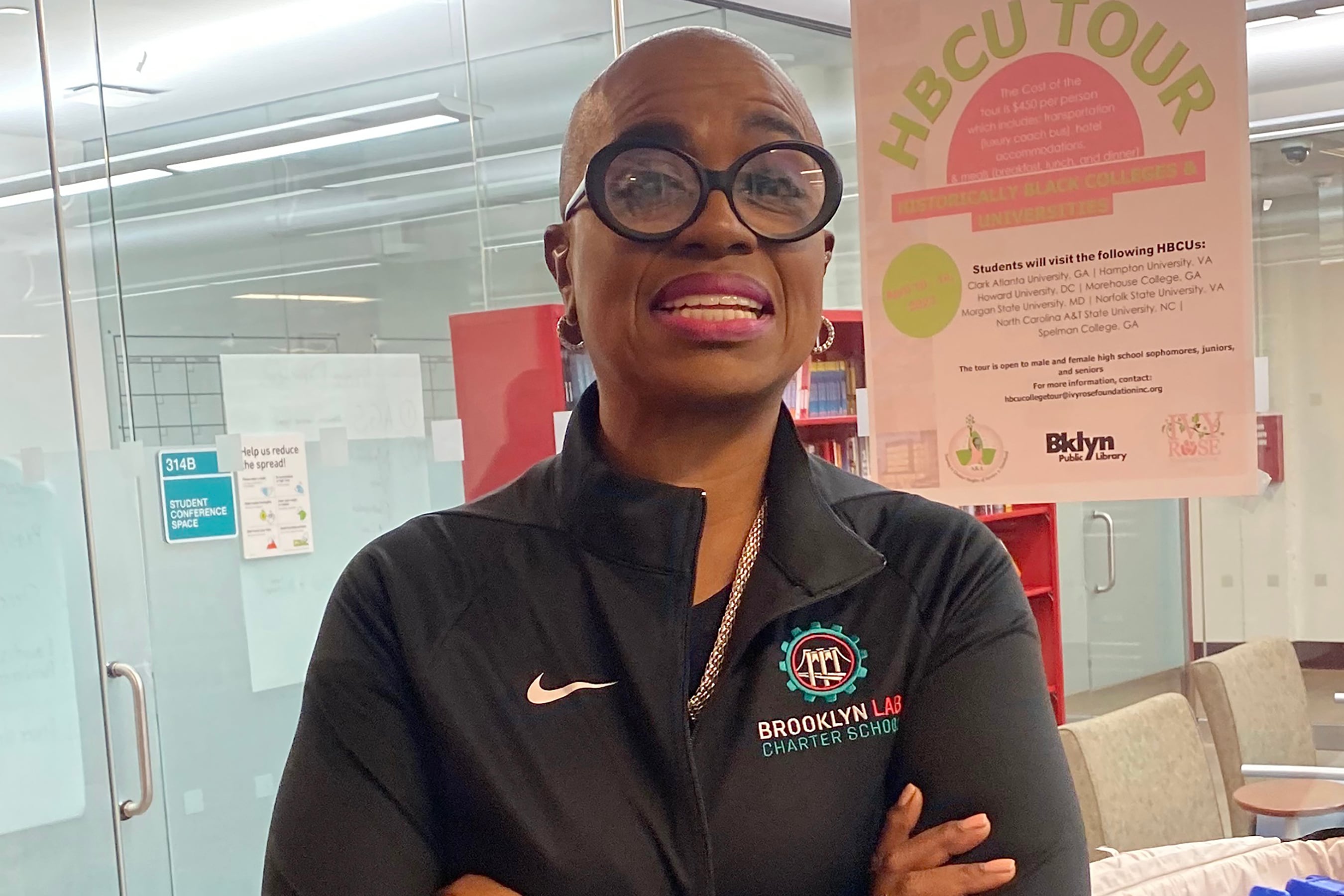

The staffer tapped for the role, Marcelle Davies-Lashley, a former city education department social worker, was skeptical at first. But she quickly discovered that many of her coworkers needed someone to talk to.

“We get to shoot the breeze and talk about whatever their stress of the day is,” Davies-Lashley said. “Sometimes it has to do with their own personal life, or with getting back to school, or scholars who are disrupting their class on a regular basis, or they’ve had a family loss. It could be anything.”

The experiment at Brooklyn Lab is part of a growing acknowledgment that many teachers are still struggling with mental health challenges three years into the pandemic and need more support. Many are dealing with unresolved trauma and grief in their personal lives while trying to regain their rhythm teaching in person and manage the mounting emotional and behavioral challenges of their students.

“Teaching has always been hard, that’s part of why I like it. But the past couple of years, it has really felt nearly impossible to do my job well,” said Brittany Kaiser, an elementary school art teacher in Manhattan. “I think the cumulative effect is what’s most hard … We can handle really big challenges, but the fact that it is one crisis after another, and repeatedly no support is available, you just hit a breaking point.”

The extent of educators’ trauma, and how it’s manifesting three years into the pandemic, is still coming into focus. A recent study found that during the height of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, teachers reported higher levels of anxiety than any other profession, including healthcare workers.

A member assistance program through the city teachers union that offers short-term counseling to educators more than quadrupled in size, from serving roughly 4,500 educators in the 2018-19 school year to around 20,000 last school year, a rise first reported by The 74.

And now the union program is going even further: partnering with the healthcare company HelloHero to match 2,500 educators with long-term therapists covered by their insurance.

Tina Puccio, the director of the United Federation of Teachers’ member assistance program, said she’s not surprised that mental health concerns have persisted, or even escalated, for some educators three years after the arrival of COVID-19.

“I remember thinking back when COVID was at its height, like God, this is going to linger. The mental anguish this is going to put on people is going to be here for a long time,” Puccio said. “And that’s still showing up.”

Educator mental health concerns have been building

When COVID hit New York City in March 2020, and schools shut down, Puccio’s program didn’t have the capacity to handle the wave of acute mental health challenges that hit educators, forcing her to put out a call for volunteers.

“I went from a staff of eight to a staff of about 300 overnight,” Puccio said. “They ran groups for me day and night, Monday through Sunday. They were talking to people at nine o’clock at night. They were calling me crying because they needed help with debriefing.”

As the acute challenges of the early pandemic faded and schools returned to in-person learning, a new set of mental health issues emerged.

Some educators confronted crippling anxiety at the thought of returning to school. Puccio recalled one member who lost her mother to COVID early in the pandemic and broke down in tears when she arrived back at school to see the empty seat of a student who had also died from COVID.

Other educators struggled to absorb a spike in behavior issues among their students after in-person school resumed while still dealing with their own lingering challenges.

“The behavior was so extreme,” said Peter, a middle school art teacher in Manhattan, who asked to use only his first name so as not to identify his school. “They [students] were traumatized, and they were acting as students with extreme levels of trauma do, and we were not prepared by any means.”

In some cases, the challenges have pushed some educators to leave the profession altogether.

At Brooklyn Lab, CEO Garland Thomas-McDavid, who started her position in July, quickly realized “people are not okay. We’re experiencing people resigning like crazy. We’ve had to do a lot to think about how do we create a workspace and structure the team to support adults so that we don’t lose all of our teachers. We need them.”

Peter left the city education department in January after his mental and physical health deteriorated.

“I struggled with depression … and all the things that come with that,” he said. “I became much less physically active. My weight, my self-esteem, my self-image declined, my relationships with friends suffered.”

Even excluding teachers who left because of the vaccine mandate, teacher turnover between fall 2022 and fall 2023 increased slightly compared to the years before the pandemic, from around 6% to 7% before the pandemic to 8% this year, an education department spokesperson said.

That echoes new data from eight states suggesting that an unusual number of teachers left the classroom after last school year.

Education department spokesperson Nathaniel Styer pointed to the agency’s Employee Assistance program and said the department has “leaned into creating emotionally supportive school environments for both students and staff, which is part of the reason we have not seen a significant drop in the retention of staff.”

Schools scramble to shore up supports

Brooklyn Lab’s experiment in providing mental health services to its staff in-house has not been without its bumps.

It took some time for word to spread and colleagues to feel comfortable opening up, Davies-Lashley conceded. But she pointed to advantages to the model as well, including having a mental health provider who’s intimately familiar with the conditions teachers are facing, and maybe even specific students.

All in all, “I think you would get a better quality educator if they knew they had this resource in the building,” she said.

Puccio, the UFT member assistance program administrator, echoed the importance — and difficulty — of building trust with educators.

“Taking care of people is their first go-to,” she said. “They’re not the first and foremost to really take care of themselves.” Puccio added many educators working in the city education department are wary of confiding in administrators, worried their disclosures could be used against them.

But after several years of steady growth, Puccio had to look outside the union to meet the burgeoning demand for mental health support, initiating the partnership with HelloHero.

Still, for some educators, help hasn’t yet arrived. Kaiser is still waiting to be matched with a mental health provider through HelloHero, and has had no luck finding a private therapist covered by her insurance.

In the meantime, she feels largely alone to confront both her own mental health challenges and those of the kids she sees each day at work.

“It creates an impossible situation,” she said. “We’re having to deal with our own issues and their issues in a society where there’s no way to address those things adequately.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.