Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for our free New York newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

The two schools sharing the Paul Robeson High School campus in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, have much in common. Both serve predominantly Black, Latino, and low-income students. Both focus on equipping students with vocational skills through career and technical education.

But on one measure, the two schools are nearly opposites.

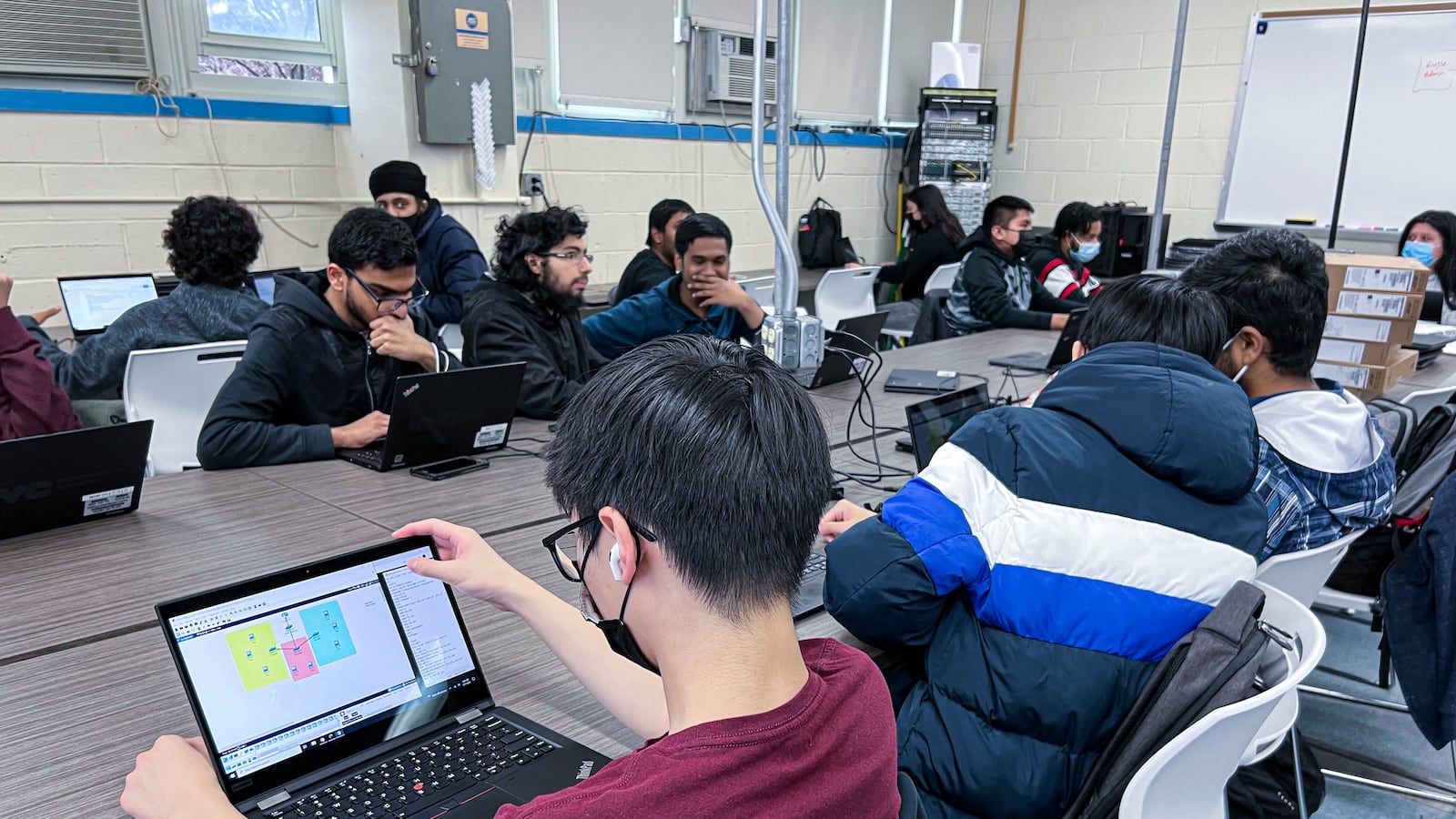

Pathways in Early Technology, or P-Tech, is 72% male, while the Academy for Health Careers is 74% female.

“It’s like we basically can’t have a prom without the other school,” joked Lisa Grevenberg, the principal of the Academy for Health Careers.

The divide in the Paul Robeson campus reflects a striking pattern that has persisted across New York City’s high schools for decades, and sets New York apart from other large districts: High school students in the five boroughs are unusually likely to attend gender-skewed schools.

A whopping 17% of New York City public high schoolers go to a school that’s at least 65% male or 65% female — or, in other words, where boys outnumber girls by at least 2 to 1, or vice versa, a Chalkbeat analysis found. Students here attend gender-skewed high schools at a minimum of three times the rate as any of the next four largest school districts in the country.

In Los Angeles, the country’s second largest district, just 4% of students attend a gender-skewed high school. In Chicago, the figure is 3%.

While the causes of the city’s gender imbalances are complex, Chalkbeat’s analysis shows a large portion of students in gender-skewed high schools attend CTE schools like those in the Paul Robeson campus. About three-fourths of dedicated CTE high schools across the city are highly gender-imbalanced, with the majority of those enrolling more boys, Chalkbeat’s analysis found.

Schools Chancellor David Banks is now poised to expand CTE even further through the rollout of two programs that help schools set up students with paid job experiences before they graduate. The education department hopes the new programs will help ease longstanding gender divides in CTE.

“It is true, our society has pushed boys and girls towards different types of jobs for decades, most notably in the traditional trade programs,” said education department spokesperson Nathaniel Styer, noting that the city’s CTE landscape most likely drove the trend uncovered by the data.

The education department is hopeful that the new CTE programs Banks is rolling out along with an existing Computer Science for All initiative can help tackle gender disparities, Styer said.

Overall, 51% of New York City high school students are male, and 49% are female, according to federal data from the 2021-2022 school year. Across New York state, 142 high school students were listed as “not specified” for gender, which could mean they are nonbinary, or data is missing. New York City didn’t record any “not specified” high school students.

The gender imbalances have profound effects on how high schools operate, presenting opportunities and challenges for educators and students.

In some cases, particularly in the roughly dozen schools across the city that are explicitly designed to be single-gender, proponents say the model can create safe spaces to address gender-specific challenges.

It’s “no secret” that Banks, who founded the all-boys Eagle Academy schools, believes “in the experience that single-gender high schools can provide students,” Styer said.

At the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women, which was created to help propel more girls into math and science, alumni have consistently praised the “community and sisterhood” that developed in a single-gender environment, said Principal Kiri Soares.

In programs that are all or predominantly male, educators like P-Tech Principal Rashid Davis say the gender imbalance allows them to zero in on the specific barriers facing Black and Latino boys, who continue to log the city’s lowest graduation rates.

“My starting point is further away from the spear of success,” Davis said of the population he serves. “It’s a completely different ballgame.”

Some proponents of CTE education argue it’s okay – and even helpful – if vocational training disproportionately helps boys, since boys face yawning gaps in educational achievement compared to girls.

The graduation rate for boys in New York City was 9 percentage points lower than that of girls in the most recent cohort.

Nationally, girls get better high school grades than boys, and now make up roughly 60% of students enrolled in college.

Richard Reeves, a Brookings Institute fellow and author of the book “Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It,” calls for federal subsidies to create 1,000 new vocational high schools as part of a plan to boost boys’ outcomes.

But gender imbalances also can present thorny problems for schools, particularly when it comes to supporting students in the minority group.

“It is tricky in a school that’s predominantly one gender or another,” said Grevenberg, the principal of the Academy for Health Careers. “How do you make sure the other gender feels like they have advocates… How do we make sure they feel they’re not boys at a girls school?”

Critics of gender segregation have for decades voiced concerns that the city’s vocational schools unintentionally reinforce gender divides in the labor market and disproportionately exclude girls from schools that could help lead to higher-paying jobs in fields like technology and computer science.

In a 2008 report titled “Blue School, Pink School: Gender Imbalance in New York City CTE High Schools,” former public advocate Betsy Gotbaum argued “young women are not equally represented in CTE programs, especially those that prepare students for higher-paying occupations.”

Evidence from other countries suggests that gender imbalance in schools is not just a reflection of gender segregation in the labor market, but actually helps create it.

There are also social ramifications of the extreme gender skews.

At one District 75 school for students with significant disabilities that, like much of the rest of the district, enrolls almost exclusively boys, a staffer expressed concerns about the impacts of the gender balance on both boys and girls.

“For our young men, socially it makes it difficult because they’re not interacting with females on a regular basis,” said the staffer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “And when they do interact with them it’s super aggressive… It’s unfortunate because we’ve had a lot of young ladies transfer out of our schools.”

The pattern has persisted for decades

Gender segregation in New York City’s high schools is not a new phenomenon.

The National Women’s Law Center traced the origins back to the early 1900s, when the city’s Board of Education explicitly prohibited boys and girls from enrolling in the same vocational schools, according to Gotbaum’s 2008 report.

Over the past two decades, New York City’s high school system transformed profoundly through the shuttering of dozens of troubled larger high schools, the opening of scores of smaller high schools, and the introduction of a choice system that allows rising ninth graders to select up to 12 choices from a list of more than 400 options.

Those changes have done little to dent the city’s unusual levels of gender segregation – and have perhaps fueled it.

“The more options you have, the more opportunities there are for sorting on many different dimensions, and gender is just one of those areas that hasn’t gotten as much attention,” said Sean Corcoran an associate professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University, who’s extensively studied New York City’s high school system.

It’s not just CTE schools contributing to the city’s high school gender imbalances.

Arts and music-focused schools that require auditions also lean heavily toward girls, with 11 of 14 audition-only schools across the city qualifying as gender-imbalanced – all in favor of girls, Chalkbeat’s analysis found.

Academically selective schools mostly don’t rise to the extreme levels of gender skew Chalkbeat targeted in its analysis, but they’re not balanced either.

Highly competitive screened schools like Beacon, Townsend Harris, and Eleanor Roosevelt that have traditionally used multiple academic measures to admit students are disproportionately female, with 16 of 27 enrolling at least 55% girls. Specialized academic schools like Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science that use a single admissions exam, by contrast, lean male, with six of eight enrolling at least 55% boys.

The names of schools alone could play an important role in driving the gender disparities, observers said.

Eighth graders may not have the time or wherewithal to deeply research each school choice, and may end up choosing schools with names that relate to their interests.

“If you look at any of the small schools that have computer and engineering in their name,” they tend to skew heavily male, noted Davis, who led the Bronx Engineering and Technology Academy before taking the helm at P-Tech.

A Chalkbeat review found 24 highly male-heavy schools with names related to computers, technology, or engineering. Another six male-heavy schools had names related to construction or sports. Among highly female-skewed schools, 15 had names relating to the arts or music, while seven had to do with health care.

Gender imbalances create challenges and opportunities

For students and educators in gender-skewed schools, the imbalances can shape everything from academic and extracurricular offerings to the school’s culture and social life.

Jaymee Warren, 18, is the only girl in the welding program at Urban Assembly New York Harbor School, which prepares students for maritime careers, and she has faced her share of challenges.

“If we’re having an open group discussion and I’m about to say an idea, someone will cut me off, and it becomes more about what the guys were saying and their group banter,” she said.

But Warren noted that the school’s staff has worked hard to make girls feel included. Supportive female staffers, in particular, make the student gender balance feel “almost equal because of the way women are empowered.”

On the other end of the gender imbalance spectrum, administrators at the Academy for Health Careers have spent significant effort and resources supporting the school’s male population.

“When I came, the success of the male students didn’t match the success of the girls,” said Grevenberg. “We had a 92% graduation rate for females and 68% for boys.”

Grevenberg brought in community-based organizations experienced in working with boys, offered extra training for her male staffers to act as mentors, and set up after-school workshops specifically for boys. Partly as a result, the graduation rate for boys at the school is now 81%, she said.

Chalkbeat’s analysis only examines gender balance at the school level, which may obscure further gender sorting that happens within schools. But gender imbalances at the school level can be particularly tricky for administrators to manage.

At one District 75 program, for example, there were so few girls that the school couldn’t justify the resources to fund a girls basketball team, said a staffer who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Research on the academic effects of gender segregation isn’t extensive, but a 2017 California State University dissertation found most of the existing evidence points to “a higher proportion of females improv[ing] the classroom and learning environment” for both boys and girls.

Principals have also gone out of their way to attract more applicants from underrepresented gender groups. Gravenberg makes sure to tap male-student tour guides when eighth grade families visit, while Harbor School Principal Jeff Chetirko makes sure to showcase female students at open houses.

But there’s only so much principals can do. While the city education department allows schools to prioritize for admissions purposes applicants from some underrepresented groups, including students from low-income families, homeless students, and English language learners, schools can’t prioritize applicants by gender unless they’re single-gender schools.

An education department spokesperson said the agency is focused on giving students “early and frequent access to careers and workspaces that were not previously on their radar.”

Officials said they’re making progress through the Computer Science for All program, noting 42% of city students who took at least one Computer Science AP exam in 2021 were girls, higher than the national average of 30%.

Warren, the welding student, has no regrets about her high school path and says she’s learned some valuable skills from being the only girl, including “realiz[ing] it’s okay to stand up for myself.”

But Warren’s college plans have taken an ironic twist: One of the schools she’s most interested in, Fashion Institute of Technology, is 82% female.

“Thinking about going to a school with mostly girls really scared me,” Warren said. “But I’ve been able to figure out who I am more, what I want to stand for, and I feel like that really helps me make connections with people now.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.

Kae Petrin is a data & graphics reporter for Chalkbeat. Contact Kae at kpetrin@chalkbeat.org.