Mayor Eric Adams’ proposed $30.7 billion budget for the education department got the green light Wednesday night from New York City’s Panel for Educational Policy.

The vote by the city’s 23-member board — largely comprised by mayoral appointees — is not the final step for the agency’s budget. Next, the mayor will release an updated version of his budget proposal, and he will then negotiate with City Council over a final plan for the new fiscal year, which starts July 1.

That means that the education department’s budget could change by the time the full city budget is adopted.

The proposed budget for the nation’s largest school system, first shared in January, is close to $340 million, or roughly 1%, less than its operating spending plan this fiscal year. The mayor called for eliminating 390 non-educator vacant positions and diverting $568 million in federal funding originally planned for expanding preschool for 3-year-olds. But Adams tried to soften some of the blows by canceling previously planned cuts to school budgets totaling $80 million.

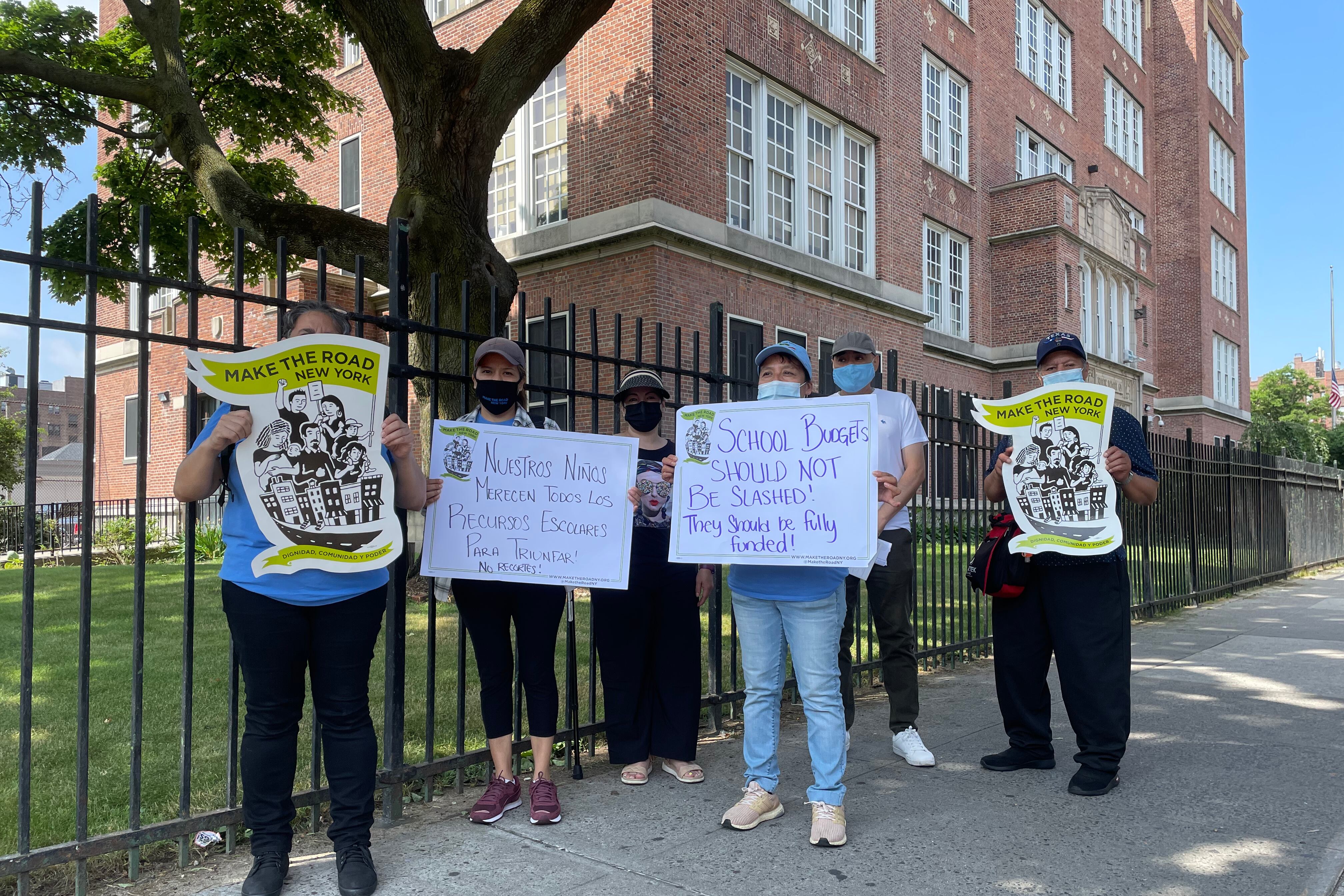

Nearly two dozen people — mostly educators and parents — spoke out against the proposed plan on Wednesday night, with several people urging the panel to push for reversing all of the cuts to school budgets.

But perhaps the most heated issue of the evening was over what wasn’t reflected in the budget: $90 million more for the Fair Student Funding formula, which is used to distribute money to schools.

In January, Chancellor David Banks and Adams proposed adding $90 million to the formula to cover new ways to calculate how much schools should get for homeless students on their rosters and for schools serving a disproportionate share of students with disabilities, English learners and those living in poverty.

The changes, which grew out of stunning criticism of the formula from the education panel last year, would impact 300 schools. The new formula is expected to come before the panel for a vote in May.

The idea of voting on those changes after the budget did not make sense to some panel members or city Comptroller Brad Lander.

“We haven’t approved the funding formula yet, so if we are talking about using a formula that we have not yet approved for calculating a budget then we are literally putting the funding cart ahead of the budget horse,” said Tom Sheppard, a parent-elected panel member from the Bronx. “I think we need to postpone this vote.”

The mayor’s panel appointees disagreed with those concerns. Several said they trusted that any changes to Fair Student Funding would be included in the final budget.

The panel’s budget vote came early because of a heated lawsuit last summer over how the budget was passed last year. In at least 11 out of the past 13 years, chancellors have bypassed the panel’s vote using an emergency declaration, according to the lawsuit. After the city cut school budgets last year, drawing intense criticism from the public, two parents and two teachers filed a lawsuit seeking to force a new vote over the budget by claiming that Banks improperly used an emergency declaration last year.

While the lawsuit wasn’t successful in forcing a new budget vote, multiple courts agreed that city officials violated state law. Because of that, the education department’s general counsel Liz Vladeck said the city decided to hold the vote early this year “to err on the side of caution.” Vladeck added that in her interpretation of the court’s decision, the panel needed to pass a budget before the mayor proposed his updated budget, known as the executive budget, in April. That schedule complicated the timing of the panel’s vote.

Lander said it was “irresponsible” to have the panel vote on the budget before a vote over Fair Student Funding, in part because city officials had not yet explained how they would pay for the additional $90 million. He suggested moving the budget vote back to May – leaving enough time for more public comment before the council has to pass a budget by July 1.

Emma Vadehra, the education department’s chief operating officer, noted that even though the budget may change by July 1, the city is bound to implement any changes to Fair Student Funding that the panel approves.

Sheppard put forth two separate motions to delay the vote over the budget until the panel’s April and May meetings, but the panel voted against them.

Multiple panel members said they didn’t have enough details on what the budget looks like for individual schools and districts. Sheree Gibson, a panel appointee for the Queens borough president, said she’s asked for several details about the budget with no clear answers, such as “how this budget impacts Queens … how it impacts our districts,” to no avail.

“In the hood, we call this balling,” said Geneal Chacon, the Bronx borough president’s appointee to the panel. “It seems like we have a bunch of money, and we just throwing it away, and we don’t even know what we spending it on.”

Reema Amin is a reporter covering New York City public schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.