Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for our free New York newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

On a recent Monday, the 12th-grade science room at Leaders High School in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, felt like a Silicon Valley startup.

Students sprawled on a couch and crisscrossed the room in rolling chairs.

Seventeen-year-old Mahmoud Hussein excitedly bounced among classmates cradling three bright red plastic shapes he’d made in a 3D printer. Hussein was collecting data on which of the objects would make the best fidget to help restless students concentrate in class without being “distracting to the eye or ear,” he explained.

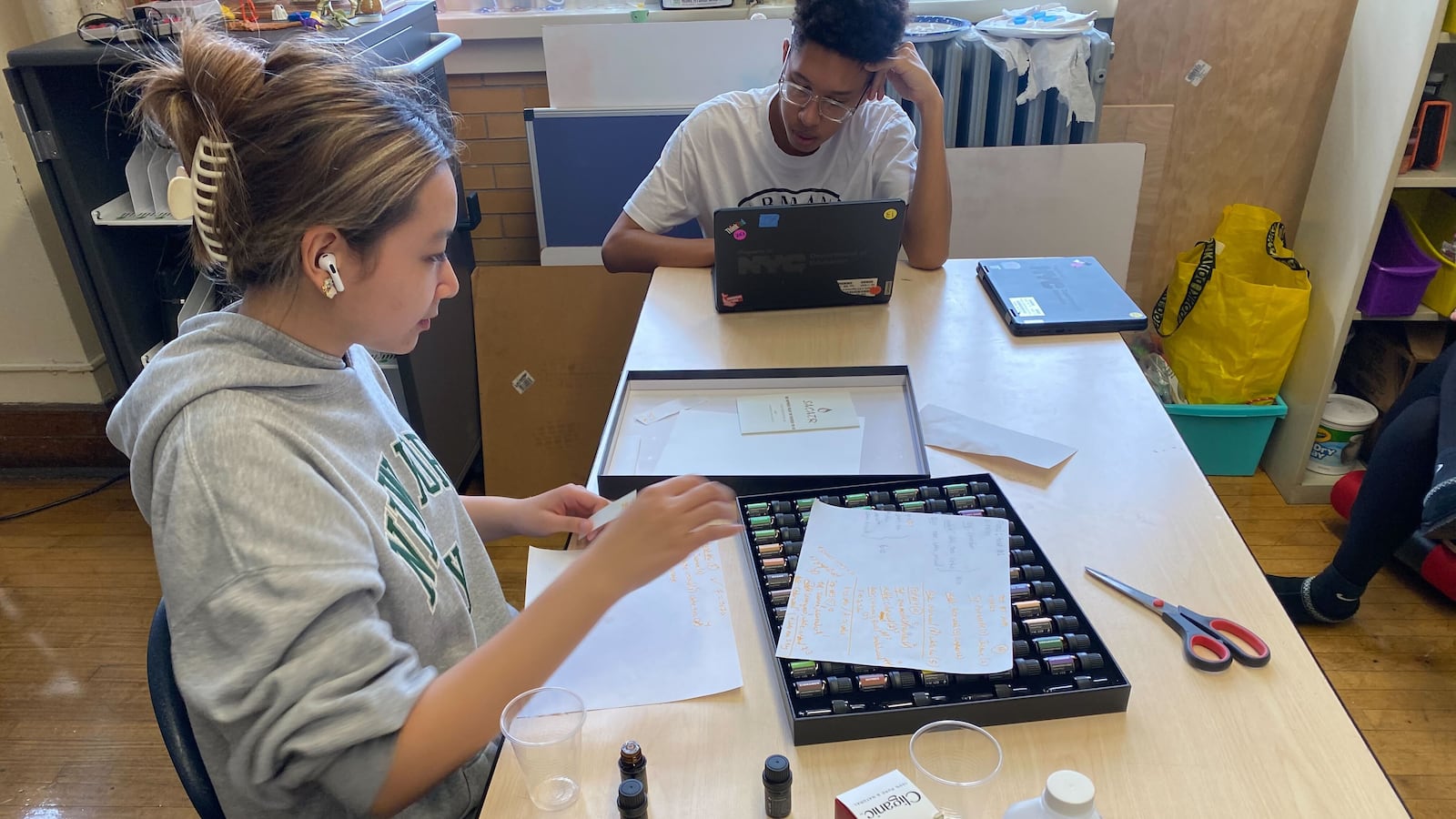

Across the room, 17-year-old Helen Chen hunched over a case of essential oils, extracting drops and mixing them together as part of a monthslong quest to develop new perfume scents free of toxic chemicals.

There’s an unusual level of student freedom. School staffers say that would be impossible without a key feature of Leaders that sets it apart from most other New York City high schools: Students here aren’t required to take year-end Regents exams that usually serve as graduation requirements.

Instead, Leaders’ seniors will document the results of their experiments and present their findings to a panel of educators and experts in what’s known as a “performance-based assessment.”

When Regents exams are the end goal, the entire curriculum is shaped to drive success on the tests, said Leaders Principal Tom Mullen. Without those tests as the final assessment, there’s a “really powerful” opportunity to reshape what and how students learn.

“It frees you up to go into much more depth into what you’re studying and allows for inquiry,” he said.

For more than two decades, a coalition of schools like Leaders has quietly offered a striking alternative to the test-based graduation system that reigns in most of the state.

The group — called the “performance standards consortium,” or “consortium” for short — launched 25 years ago with a handful of schools and now comprises 38 members that receive waivers from the state to forgo Regents exams, except the English test. All but two are in New York City.

For most of its history, the consortium has attracted fervent support from its students, parents, and educators, but has operated largely under the radar for most families and policymakers.

That may be changing now as the state reaches a crucial point in a yearslong effort to rethink graduation requirements, casting a new spotlight on performance-based assessment and the work of the consortium.

Students from consortium schools post better college outcomes

Proponents argue that, when done well, performance-based assessments can be just as rigorous, or more so, than tests, and encourage deeper learning that will better serve students in college and the work world.

They point to data including a 2020 study comparing the trajectory of consortium and traditional public school students at CUNY. The analysis found teens from consortium schools were more likely than peers with similar backgrounds from traditional public schools to graduate high school, enroll in higher education, and persist once they got there.

The model has even attracted praise from both ends of the political spectrum. Ray Domanico of the right-leaning Manhattan Institute argued that consortium schools’ “success in getting graduates into college — and the success of their students once they are in college — gets much less attention than they deserve.”

Members of the state’s blue ribbon commission for re-evaluating graduation requirements may soon be paying more attention.

This fall, the commission will present recommendations to the Board of Regents on whether to maintain Regents exams as graduation requirements, and, if not, what to use in their place.

A recent report conducted on behalf of the state education department and Board of Regents said performance-based assessment was the single most popular topic brought up at listening sessions it conducted across the state.

The state education department, meanwhile, is running a pilot program to collect more data on the potential of expanding performance-based assessments. The pilot won’t conclude until 2027, but state education department officials said the group is already communicating its preliminary findings to the blue ribbon commission.

“It’s now very popular to talk about performance standards,” said Michelle Fine, a professor at CUNY’s Graduate Center who has been evaluating the consortium schools since their inception.

The newfound interest is both exciting and nerve-racking for those invested in the consortium.

On one hand, supporters believe there’s room for the model to grow, and that performance-based assessment could play an important role in revamped state graduation requirements.

But proponents also warn that the approach requires a significant level of buy-in and work that may not be right for every school. Moreover, some supporters worry that the rigorous assessment system they’ve worked decades to hone could get watered down as the model expands.

“Everyone who works in a school has seen something called a ‘project’ that’s really just a stack of papers,” said AJ Rathmann-Noonan, the director of school support for the consortium. If a similar fate befalls performance assessments, “it becomes harder to make the case that this is a rigorous alternative to the Regents.”

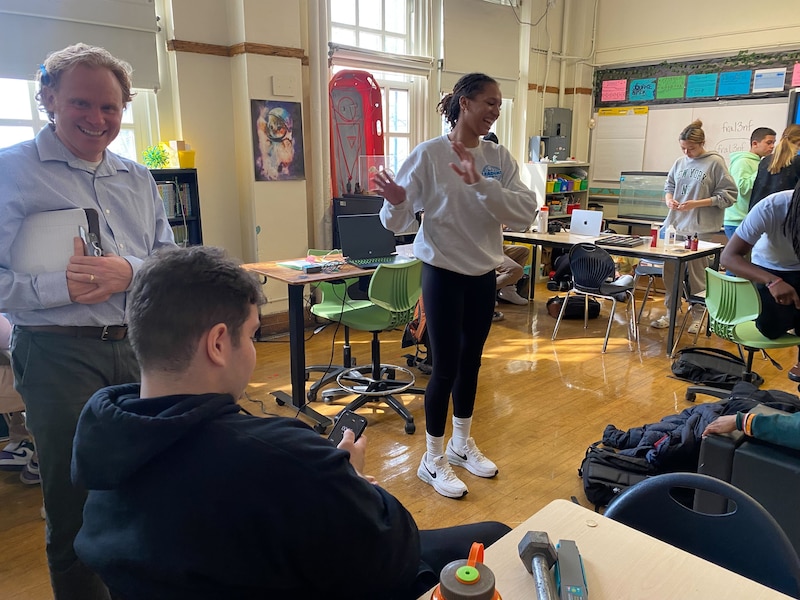

That’s why proponents of the approach are now working hard to disseminate what they see as the cardinal lessons about what makes the model work — and even bringing in members of the state Board of Regents for visits to see the assessments in person.

Related: My high school is exempt from Regents exams. Other schools should be, too.

Among the biggest takeaways consortium educators want to communicate: the importance of having a network of peer schools to work alongside, securing widespread buy-in from staff before switching to performance assessments, and perhaps most importantly, the impossibility of juggling Regents and performance assessments at the same time.

“You can’t split your attention between traditional and performance assessment,” Rathmann-Noonan said. “We want to make sure those lessons are surfaced so people don’t make the same mistakes.”

Leaders High School makes the leap to a new system

Staffers at Leaders High School understand firsthand both the benefits and challenges of switching from Regents testing to a new kind of assessment.

The school was part of a wave that joined the consortium after state officials agreed in 2013 to issue more waivers.

At the time, staffers at Leaders were eager to experiment with new methods of teaching, but were frustrated by having to prepare for Regents. They also were concerned about the tests’ effects on vulnerable students.

Many staffers felt the Regents weren’t “showing what kids know,” said special education teacher Alexandra Edwards. “We had all these students that had testing anxiety, and we had a big English language learners and special education population.”

The school had to clear a high bar to join the consortium: New entrants are required to hold a staff-wide referendum and secure support from every employee before they can join. That’s the only way to ensure schools are fully prepared for the workload and “level of collective effort” ahead, said Rathmann-Noonan.

Staffers remember that first year as a blur of activity. Teachers spent extra professional development days reworking curriculum plans from top to bottom, getting familiar with the new assessment system, and visiting other consortium schools to pick up tips.

Four graduation-level Performance-Based Assessment Tasks, or PBATs, serve as the North Star for consortium schools: a capstone science experiment, a social studies research paper, an analytic English essay, and a math “narrative” in which students describe the process of solving a math problem.

For each performance assessment, students deliver both a written component and an oral presentation to a panel of teachers, experts, and community members that students themselves play a part in selecting. Schools across the consortium have a unified system for grading the assessments, which draw from the same state standards that guide the Regents exams. Consortium staffers meet frequently to revise the grading system.

Teachers at Leaders quickly learned that preparing students for PBATs was a very different journey than getting them ready for Regents.

The entire faculty had to work together to design a four-year sequence that equipped students not just with content knowledge but also the more intangible skills they needed to complete long-term research papers and experiments.

As time went on and staff settled into a rhythm, they noticed that, even as some aspects of their job got harder, others became easier.

“I have so much less work when it comes to classroom management. I have so much less work when it comes to rote grading,” said English teacher Dana Nelson. “My work is really having the emotional stamina to consider each student and where they are.”

Ten years into using performance assessments, she’s still tweaking her PBAT every year, Nelson added.

“There’s no such thing here as the grizzled veteran who has the yellow pad of tried-and-true things that has been the same for however many years,” she said. “You constantly have to reflect and revise and change.”

In the long term, educators say, that can lead to greater job satisfaction, and could be part of why teacher retention rates in consortium schools exceeded citywide averages from 2011 to 2016, the CUNY study found.

The added curricular freedom also forces students to think much more deeply about what they’re really interested in, starting from an early age, staffers said.

Inspired by her own heritage, 18-year-old Fernanda Carrillo, wrote about Mexican immigration during the Trump administration for a history prompt on how communities have resisted oppression.

Zeroing in on her interests helped keep her from disengaging during the pandemic.

“Because of COVID my grades were suffering,” she said. “It really helped that they let me do what I want to do.”

Applying the consortium’s lessons statewide

Supporters of the consortium model say that the lessons schools like Leaders have learned should help inform the state’s approach to incorporating performance-based assessments into its graduation requirements.

How exactly those requirements could change is still blurry.

Sheree Gibson, a Queens parent and member of the city’s Panel for Educational Policy, who’s also on the state’s blue ribbon graduation measures committee, said that while there’s been widespread discussion of reducing the role of the Regents exams in graduation requirements, she’s heard little momentum to scrap the tests altogether.

That means that Regents tests will likely continue to play some role in the state’s graduation landscape, just alongside other “pathways” like performance-based assessments.

Consortium supporters are adamant that requiring schools to simultaneously offer both styles of assessment at once isn’t effective.

They point to recent efforts to expand performance-based assessment in New Hampshire as a cautionary tale.

University of Massachusetts researchers found in a 2022 review that the requirement to simultaneously use performance and test-based assessments “created two conflicting goals” for educators.

Experts on the model also caution that schools have to be intentional about explaining it to families, particularly those in communities that have been historically underserved by schools and crave external accountability.

Staff at Leaders say many of the families who enroll their students as ninth graders come in without fully understanding the consortium model. A handful decide that it’s not the right place for their kids and leave, but many others come around to the approach once they get to talk it through with staff.

Often, the discussion turns back to what parents really want their kids to leave high school with: the ability to speak and write with confidence, think critically, manage their time and work independently, and identify and pursue their passions — precisely the qualities educators say performance-based assessment encourages.

“It’s making those connections for parents,” said Edwards, the special education teacher. “Those are all really important skills just for existing in the world.”

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org.