Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Chancellor David Banks is planning the most aggressive overhaul to the way New York City schools teach students to read in nearly 20 years.

The changes, announced this week, will require the city’s elementary schools to adopt one of three reading programs over the next two years. They must also phase out materials from a popular “balanced literacy” curriculum developed by Lucy Calkins, a professor at Teachers College, which has been used by hundreds of elementary schools in recent years.

“A big part of the bad guidance was rooted in what has been called balanced literacy,” Banks said this week. “We must give children the basic foundational skills of reading.”

But what is balanced literacy, anyway? And how are the new curriculums different?

Here’s how the changes could impact students in grades K-5:

What reading strategies is the city moving away from?

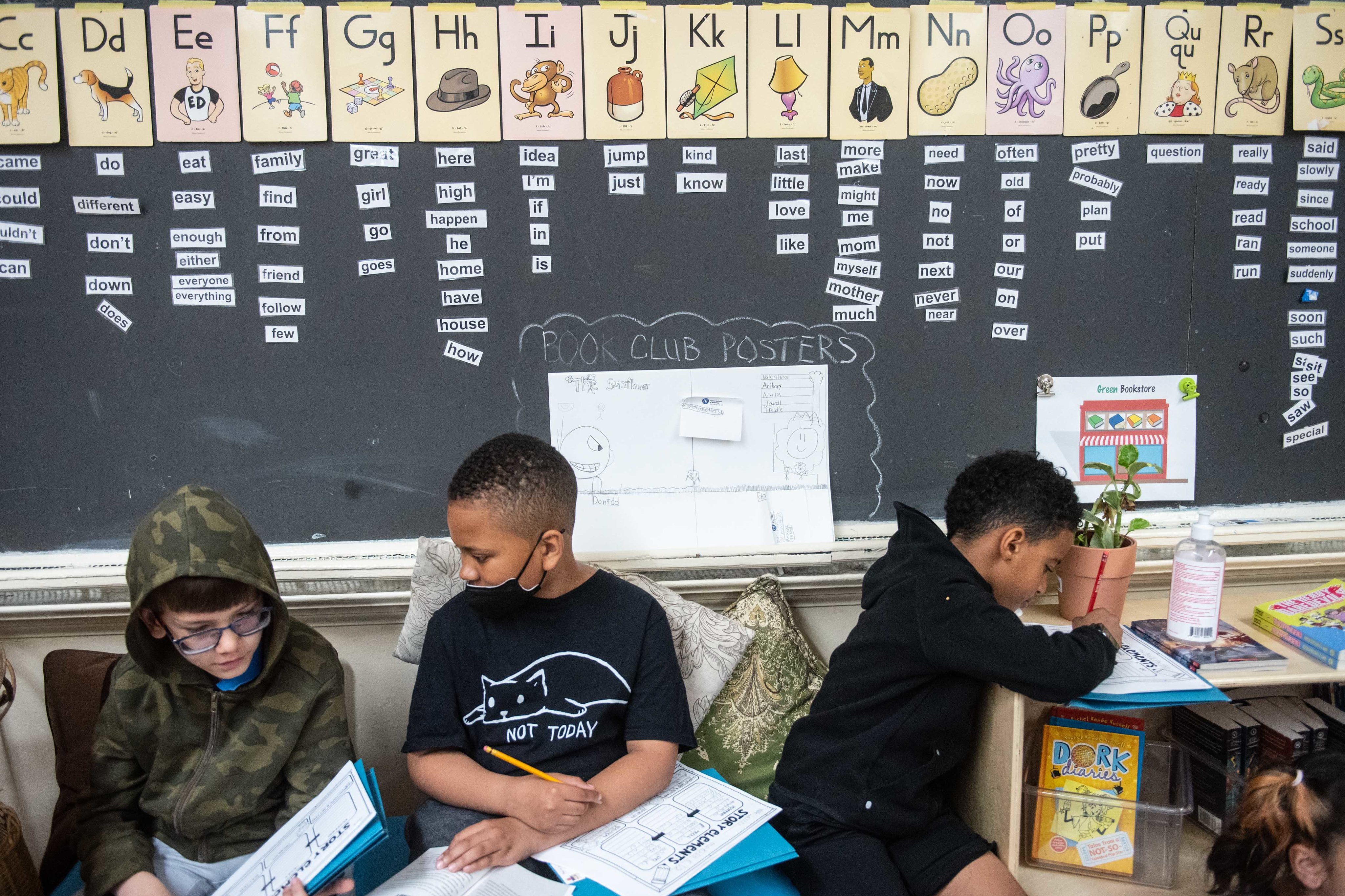

For years, many New York City schools embraced a philosophy of reading instruction as a natural process that can be unlocked by exposing students to literature. The idea was that by filling classroom libraries and giving students freedom to pick from them, they would develop a love of reading and absorb key skills to decipher texts.

In many classrooms, teachers offered mini-lessons on topics like how to find a text’s main idea. Then students were often sent to select a book of their choice, geared toward their individual reading level, to read independently and apply skills from the lesson they’d just heard. If a child had trouble identifying a specific word, they were often encouraged to use accompanying pictures to guess at its meaning, a practice that has been discredited.

Critics said the approach lacked sufficient instruction on the relationship between sounds and letters, known as phonics. In response, supporters of the model sprinkled more of it in. That compromise is known as balanced literacy. Balanced literacy was pushed into schools by the city’s education department in 2003, and it has remained popular.

Before the pandemic, roughly half of city elementary schools that responded to a curriculum survey were using a balanced literacy program called Units of Study, developed by Calkins, an investigation by Chalkbeat and THE CITY found. (Calkins has since updated the program, including a greater emphasis on phonics, though most schools will not be allowed to keep using it.)

In practice, instructional approaches often differ from school to school — or even classroom to classroom — with teachers often piecing together lessons from a hodgepodge of different sources. The city’s goal is to ensure all schools have access to, and actually use, high-quality materials.

What is the approach to phonics?

Balanced literacy has increasingly come under fire from a range of experts who point to long-standing research that shows many students won’t pick up reading skills without more systematic instruction on the fundamentals of reading.

Now, all elementary schools are being required to adopt city-approved phonics programs, explicit lessons that drill the relationship between sounds and letters. Those programs are typically delivered separately from a school’s main reading program and are shorter in length, often about 20-30 minutes.

Even before the latest mandates, most schools were already delivering some phonics, though observers said getting schools to use the same approaches will help streamline training and oversight.

“Many, many schools have adopted a coherent phonics approach over the past few years, but the difference is we’re now organizing the infrastructure … to be able to work together around a common playbook,” said Lynette Guastaferro, CEO of Teaching Matters, an organization that works with about 160 New York City schools to improve reading and math instruction.

What’s the philosophy behind the new curriculums?

In addition to phonics lessons, all elementary schools will be required to use one of three reading curriculums: Wit & Wisdom, from a company called Great Minds; Into Reading from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; or EL Education.

Many curriculums focus on reading strategies, such as how to find a text’s main idea or how to draw conclusions from it. But the three required curriculums build students’ background knowledge in science and social studies.

The idea is that a student’s ability to understand what they’re reading depends on how much prior knowledge they have of the subject at hand. In one famous experiment conducted in the 1980s, researchers found that children who were not strong readers but knew a lot about baseball were just as capable of summarizing what they’d read about a baseball game compared with stronger readers. (A recent study offers fresh evidence that the knowledge-building approach may be effective, though research is limited on whether knowledge-based programs outperform skills-focused curriculums.)

Kate Gutwillig, a fourth and fifth grade teacher at P.S. 51 in Manhattan, previously used Calkins’ balanced literacy program but in recent years transitioned to EL Education and now uses Wit & Wisdom.

She said she appreciated EL Education’s social-justice oriented lessons, including one where students unpack the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and also read a novel about a girl who must flee Mexico with her family and winds up in a farm labor camp in California. More recently, she taught a Wit & Wisdom unit focused on the heart’s role in the circulatory system and the way it’s used figuratively to refer to love and other emotional qualities.

“They’re thriving, they’re doing so well with it,” Gutwillig said of her students. Unlike the balanced literacy program where students picked their own books, students are all reading from the same books at the same time. “It helps to build community,” she said.

Some advocates argue that Into Reading doesn’t have as strong a focus on knowledge building compared with the other two programs, in part because it includes such a wide range of materials, but it has still received high marks from curriculum reviewers.

Which curriculum is your school likely to use?

Thirteen of the 15 districts expected to adopt one of the three approved reading programs this September have selected Into Reading. That curriculum uses an anthology-style textbook with texts specifically designed to teach reading skills. Some observers said the lessons tend to be scripted, and department officials said its “teacher friendly” approach made it a favorite among the local superintendents charged with picking a curriculum for their district’s schools.

“The lessons are laid out so the teacher can walk in and teach them,” said Heidi Donohue, an early literacy expert at Teaching Matters. Into Reading tends to move more quickly through multiple texts each week, she said, whereas Wit & Wisdom and EL Education tend to stay on one text or unit for longer stretches.

Into Reading “has everything that teachers would want,” said Merryl Casanova, a literacy coach who works with schools in the Bronx, pointing to materials that focus on grammar, spelling, reading comprehension, discussion strategies, and more. But that can also be “very overwhelming,” she said. “Teachers really have to plan for this, and they have to understand that they’re not going to use all of the resources.”

Into Reading has received some criticism for not reflecting the diversity of New York City’s student population, which is predominantly Black and Latino. A New York University report found that the program “used language and tone that demeaned and dehumanized Black, Indigenous and characters of color, while encouraging empathy and connection with White characters.”

Officials at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, which publishes Into Reading, have disputed that characterization, arguing that the report focused on a small sample of materials. The city’s education department said schools may also supplement the curriculum with other materials that are designed to be culturally responsive.

All three curriculums have passed muster with EdReports, an independent curriculum reviewer.

Which schools will be covered by the mandate first?

Many schools among the first 15 districts covered by the mandate already use their district’s approved curriculum or are in the process of doing so, city officials said.

The city’s remaining 17 districts will not fall under the mandate until September 2024. City officials said some schools may receive exemptions, which have not yet been revealed, though they emphasized that they expect the number will be small.

Here’s what each district has selected so far:

Into Reading

Manhattan District 5

Bronx District 12

Brooklyn districts 14, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23, 32

Queens districts 25, 26, 29, 30

Select schools in District 75, a citywide district for students with more complex disabilities

EL Education

Bronx District 11

Wit & Wisdom

Brooklyn District 19

How long will it take to see changes?

Experts and educators said that curriculum changes often take years to fully take root, and may depend on how committed teachers and school leaders are to the changes. (The city’s principals union, for instance, has pushed back against the mandate.)

At P.S. 236 in the Bronx, educators began transitioning to Wit & Wisdom in 2020 after using Calkins’ Units of Study for years. Lauren Litman, a second grade teacher, said educators have been learning how to deploy texts that students often find challenging and figuring out how to edit the curriculum down to be manageable.

“We’ve kind of gotten into a better rhythm of how to scale down the lessons because there is a lot of information,” she said.

How quickly teaching practice changes may also depend on how effective the city’s training is — and there’s limited time to help educators learn new materials before September.

“Any new curriculum is going to take time for us to get the routines and the systems and the things in place that are going to make it work for the school,” Donohue said. “No curriculum is going to be the quick fix.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.