Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

New York City’s education department plans to ditch a controversial social skills assessment for the coming school year, Chalkbeat has learned.

The tool’s proponents believe it’s a missed opportunity to help shift school culture to become more responsive to children’s social-emotional wellbeing, particularly at a time when needs are high.

In many ways, however, the tool’s rollout was doomed from the start.

Officials knew that students would have increased mental health demands when they returned to classrooms last year. They promised to be ready.

It was December 2020, long before the start of the new school year, when officials released a “mental health and wellbeing plan,” highlighting how schools would use a five-minute assessment to quickly identify significant emotional issues. The results would help flag individuals who needed more intensive interventions and support.

About eight months after that announcement, the city approved a 3-year $18 million contract to Aperture, an education technology company that created a platform to administer what’s known as the Devereux Student Strengths Assessment, or DESSA.

A few months later, in October 2021, education department officials shared the assessment tool with teachers, giving them a short runway to figure out how to utilize it.

The backlash against the DESSA was swift. Teachers feared they didn’t know their students well enough and that their responses could be biased. Many revolted against the directive to administer it, asking parents to opt out. Parents from various ends of the political spectrum refused to have their kids assessed. Some had concerns about privacy and data security, others worried about the questions’ overreach and the time it would take teachers away from building relationships with their children.

Many questioned the cost of the tool — though broken down by school, it came to roughly $3,300 a year for each school.

This year, the education department quietly backed off the initiative, making it optional for schools to administer the DESSA. Many educators told Chalkbeat that their schools ditched it. Education department officials declined to disclose how many schools continue to use it, but confirmed that the citywide DESSA program is expected to be discontinued in the coming school year.

“Broad implementation of the screener was only a temporary initiative,” education department spokesperson Jenna Lyle said in an email. “While the screener will no longer be administered city-wide, the practice has helped schools to understand the importance of identifying students who may be in need of additional support and prioritizing wellness among the entire school community.”

Schools can continue to implement social-emotional screening assessments, if they choose to, and the department is available to assist with that process, she said.

Related: How to get mental health help in NYC public schools

For David Adams, the CEO of Urban Assembly, a network of about two dozen schools across the city that have long incorporated the DESSA, the assessment tool is critical, especially at a time when many kids don’t feel like they have a trusted adult on campus.

Of the sixth through 12th graders across the city who responded to last year’s school survey, more than 1 in 5 did not have at least one adult in the school they could confide in.

The criticism from teachers about not knowing their students well enough to fill out the assessments is precisely the reason that it’s needed, Adams said.

“The tool becomes the intervention,” he said. “A teacher who is paying attention to student interactions will be able to fill it out. A teacher who doesn’t know their students, isn’t collaborative with them… that’s where you’re seeing the opportunity.”

Problems with DESSA rollout

The messaging around the initial announcement of the mental health plan laid some of the groundwork for pushback. Educators and parents worried about overstepping boundaries when it came to evaluating kids’ mental health.

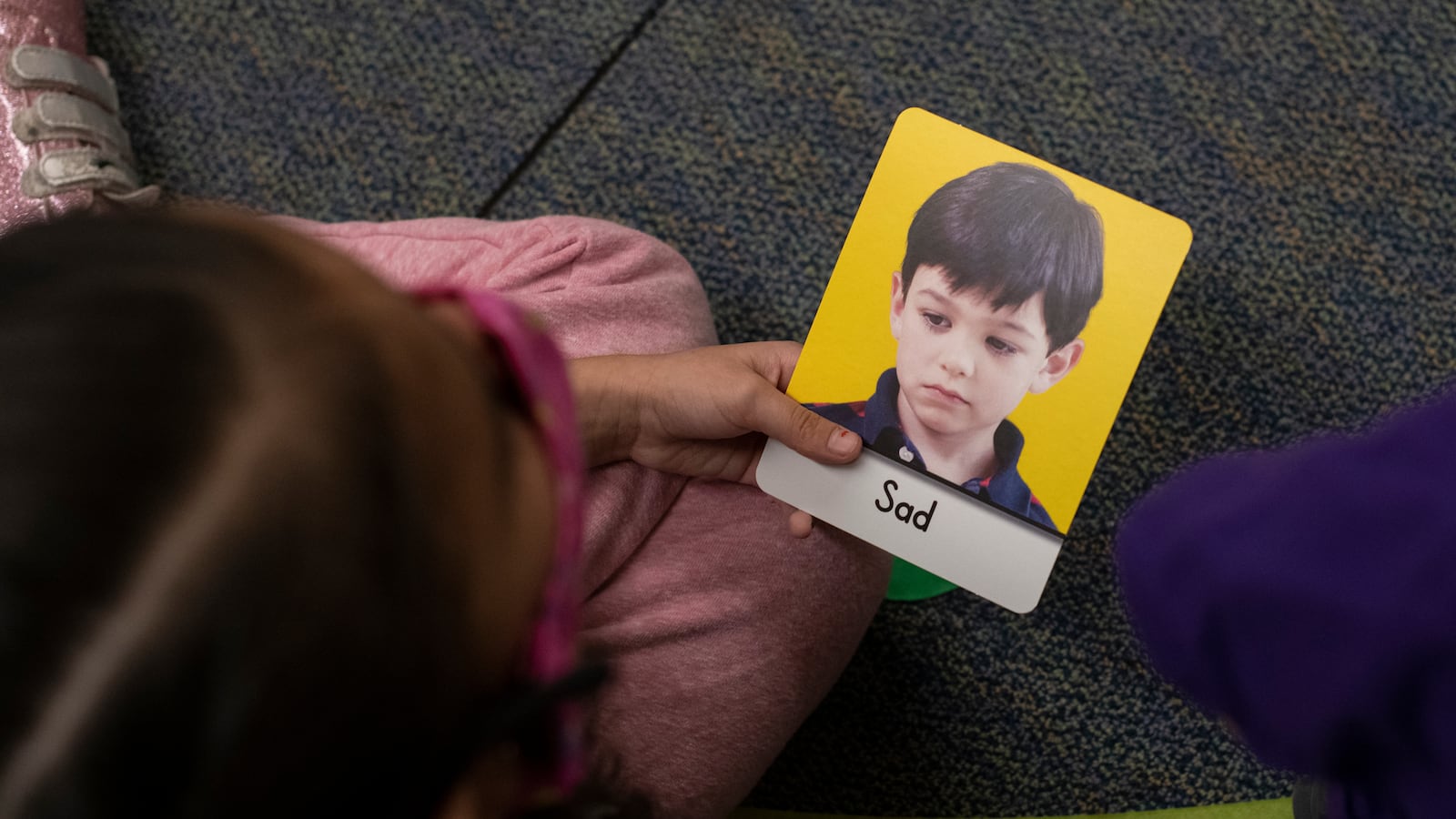

The DESSA, however, is not about identifying mental health issues. It aims to gauge social skills such as decision-making, self-awareness, and taking personal responsibility. Among the 40 questions: During the past four weeks, how often did the child keep trying when unsuccessful? Get things done within a timely fashion? Show good judgment? Offer to help somebody?

It also often took more than five minutes for a teacher to fill out the questions for each student. Teachers were expected to fill it out in the fall and spring to track a student’s social-emotional arc over the year. It often felt like one more burden, teachers said.

Moreover, several educators told Chalkbeat they didn’t know how the results were used and didn’t think that schools got more support for counselors if they ended up flagging students who needed more help.

“Vague promises were made about school-level support that might materialize depending on the results of the DESSA screeners,” said Brittany Kaiser, an art teacher at the Earth School, an elementary school in Manhattan’s East Village. “We were, and are, in desperate need of more guidance counselors and social workers, more funding for other support positions, and trainings on trauma-informed teaching, de-escalation strategies, restorative justice implementation, and conflict resolution strategies.”

That support, however, never materialized, she said.

When the tool was made optional this year, Kaiser’s school dropped it.

Overall, fewer Manhattan schools filled out the DESSA than their counterparts in other boroughs, according to fall 2022 data obtained by Chalkbeat. Roughly 67% of Manhattan schools used the tool in the fall, while about 75% in Brooklyn and Queens did. Schools in Staten Island and the Bronx had the highest rates at 84% and 80%, respectively.

The education department tried to make it easier to administer the DESSA, giving high schools the option of having students fill out the questionnaire themselves, while elementary and middle schools could allow parents to fill out the questions, according to updated guidance sent to principals earlier this year. Officials also told schools they could tap federal relief funding to pay teachers extra for filling out the tool beyond the school day.

Allowing students and parents to fill out the form dilutes the intent, Adams said. He sees the tool as a way to get teachers to pay closer attention to their students through a “strength-based” framework and give educators a common language on how to discuss those skills.

Adams compared the assessment to an approach that a coach uses for athletes, observing and giving suggestions based on those observations. Rather than a screener, Adams views the DESSA as a “feedback tool.”

“The goal is not ultimately about having people rate kids,” he said. “It’s about every kid having social emotional competence and teachers learning to see and give feedback on that. Feedback drives learning.”

Teachers are often giving feedback on social-emotional skills that’s tied up in grades, Adams said. They might, for instance, conflate mastery of a topic with things like deadlines. The tool provides a way to tease that apart and enable a teacher to discuss the importance of responsibility and turning assignments in on time. Rather than simply taking 10 points off on an assignment, for example, it gives the teacher “the language and the clarity” to talk about certain skills a student needs to be successful.

According to Adams, about 47% of a student’s grade is linked to social-emotional competency scores, and the DESSA, he believes, can help schools address issues, such as goal-setting, which affect academic performance.

Using the tool to change teaching and learning

The Urban Assembly network began incorporating the DESSA years ago, after seeing how nonprofit youth development organizations, such as the Children’s Aid Society, were using it to focus on social-emotional outcomes. The network employs 14 social-emotional learning specialists that fan out to schools to assist them with how to use the DESSA. (Meisha Porter, who was chancellor at the time the city selected the DESSA, had been a principal of an Urban Assembly school — after taking over from current Chancellor David Banks.) But the intensive assistance from the Urban Assembly was never scaled across the system, leaving many schools adrift when it came to incorporating the tool.

“If it feels like an add on…it’s not going to be useful,” said Delia Veve, principal of Manhattan’s Urban Assembly Media High School. “If people are doing it out of compliance and begrudgingly, then it’s about checking a box. What does that accomplish?”

The school goes all in on the tool. Before they administer it for their students, the adults at Veve’s school study the skills on the DESSA, to help them reflect on what they mean and how they might show up, the principal explained. Then, each of the roughly 350 students are assessed twice a year by at least two different adults, including the teacher from advisory, to help address possible biases in responses.

“I recognize that’s a heavy lift,” Veve said, “but it does make that data that much more reliable.”

Her school uses results from the DESSA less for identifying individuals who need more dedicated support and more for identifying trends across the grades to change teaching practices.

The school noticed last year that relationship skills were a bigger area of weakness than previously, which was unsurprising given the prolonged isolation during the pandemic and the continued COVID mitigations last year that prevented a lot of group work. So this year, the school bolstered opportunities for kids to work collaboratively.

Rather than view the responses as an issue where students aren’t demonstrating certain competencies, it reveals where the school might not be creating the space to meet their needs.

It helps her see, Veve said, “Is it a reflection of the kid or is it a reflection of the school?”

Need for a holistic approach to help kids

Without a lot of support, however, many schools floundered with the DESSA. One Bronx administrator explained that her school dropped the DESSA because it felt redundant to what they already had in place. The school prides itself on having a robust team for social-emotional support: It has three guidance counselors and two social workers who help lead weekly advisory groups and small group counseling for its roughly 600 students.

The advisory groups, in particular, focus on social-emotional learning and peer relationships, and they provide insights to the counseling team when issues might arise, said the administrator, who requested anonymity. Whether a school offers an advisory period often comes down to carving out space in the schedule and making tradeoffs, the administrator explained. For them, it meant giving up other electives, like robotics.

If her school’s team didn’t have such a strong counseling infrastructure in place, she might have found the DESSA more helpful, she said. She thought it was worthwhile to figure out a way to measure social-emotional learning metrics, she said.

The ways schools have incorporated the DESSA was uneven, with some schools more focused than others on how to use the tool to identify students who need help, said Kevin Dahill-Fuchel, executive director of Counseling in Schools, which provides counseling services at roughly 70 schools across the city.

Yet, while the tool might not give a parent a definitive answer about how their child is doing, Dahill-Fuchel didn’t think it seemed harmful. But there’s not always a clear plan on what should happen next with the data.

“There’s not a robust accountability system,” Dahill-Fuchel said.

Having such a system is important to shift a school’s culture toward a more supportive environment, he said.

“Where we need to get to ultimately,” Dahill-Fuchel said, “is that schools get held accountable for social skill development and emotional wellbeing in the same way they do for academic progress.”

Amy Zimmer is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat New York. Contact Amy at azimmer@chalkbeat.org.